What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

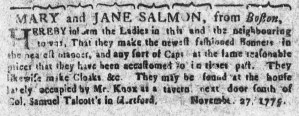

“Newest fashioned Bonnets … at the same reasonable prices that they have been accustomed to in times past.”

When they relocated to Hartford, milliners Mary Salmon and Jane Salmon placed an advertisement in the December 4, 1775, edition of the Connecticut Courant to introduce themselves to their new neighbors and, especially, to prospective customers. They informed “the Ladies in this and the neighbouring towns, That they make the newest fashioned Bonnets in the neatest manner, and any sort of Caps.” They also noted that they “make Cloaks” and other garments. The milliners hoped to establish a clientele and earn their livelihood in a town new to them. In the headline for their advertisement, they described themselves as “from Boston.” The Salmons were not the only newcomers from Boston who ran an advertisement in that issue of the Connecticut Courant. James Lamb and Son, tailors “From Boston” who had previously inserted a notice in that newspaper in September, ran a new advertisement that appeared in the same column as the Salmons’ notice. Like the Lambs, the Salmons may have been refugees who left Boston following the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington and Concord in the spring.

In marketing their wares, the Salmons did not allow the difficulties of the war to overshadow prospective customers’ desire for hats that followed the latest styles. They intentionally declared that they made “the newest fashioned Bonnets” and did so “in the neatest manner.” They combined appeals to taste with a pledge about the quality of their hats and their skill as milliners. The Salmons also incorporated promises regarding price into their brief advertisement, asserting that they charged “the same reasonable prices that [prospective customers] have been accustomed to in times past.” The disruptions caused by the war did not cause them to raise prices. In addition, they made a nod to the ninth article of the Continental Association: “That such as are Venders of Goods or Merchandise will not take Advantage of the Scarcity of Goods that may be occasioned by this Association, but will sell the same at the Rates we have been respectively accustomed to do so for twelve Months last past.” The Salmons could not rely on their reputation among an existing clientele to generate business as they had done in Boston. Instead, they devised an advertisement that said a lot in just a few lines, deploying appeals to fashion, quality, skill, and price. They may have also expected that current events would resonate with their notice, anticipating that prospective customers would realize why they moved from Boston and their commitment to abiding by the Continental Association.