What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He continues to carry on the PAINTING and GLAZING BUSINESS.”

Colonial printers often resorted to publishing advertising supplements to accompany their weekly newspapers that featured both news and paid notices. This was especially true for newspapers in the largest port cities, Boston, Charleston, New York, and Philadelphia. Each standard issue consisted of four pages created by printing two pages on each side of a broadsheet and then folding it in half. When printers had sufficient additional content to justify the resources required to produce additional pages, they printed two- or four-page supplements. Although news sometimes appeared in those supplements, additions, and extraordinary editions, they most often consisted of advertising.

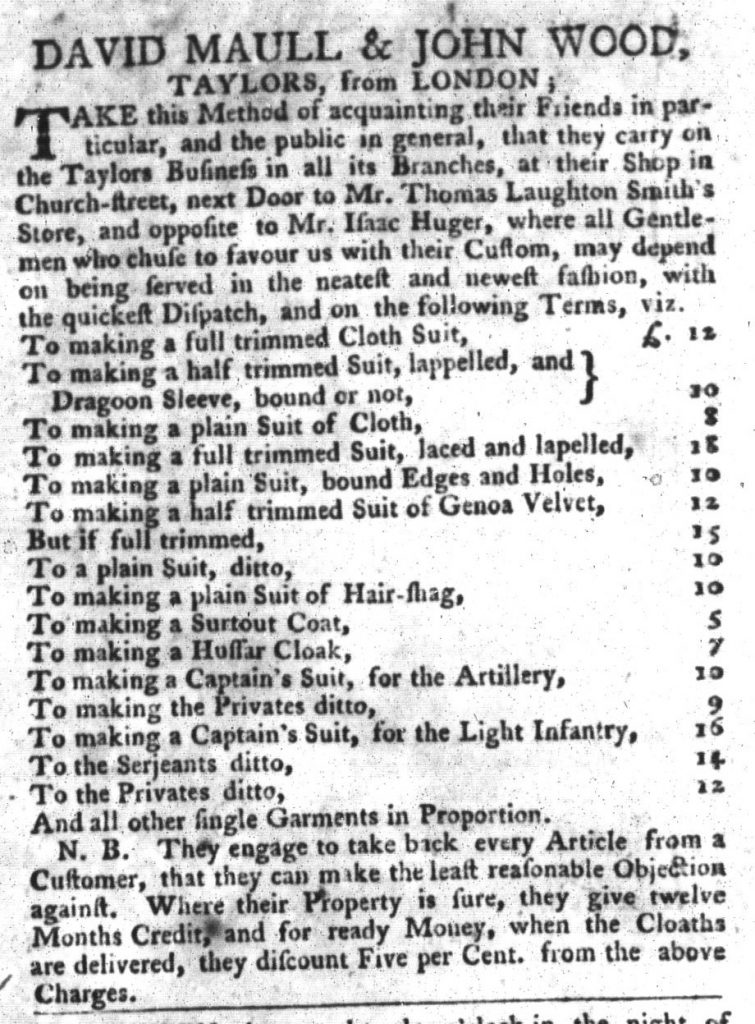

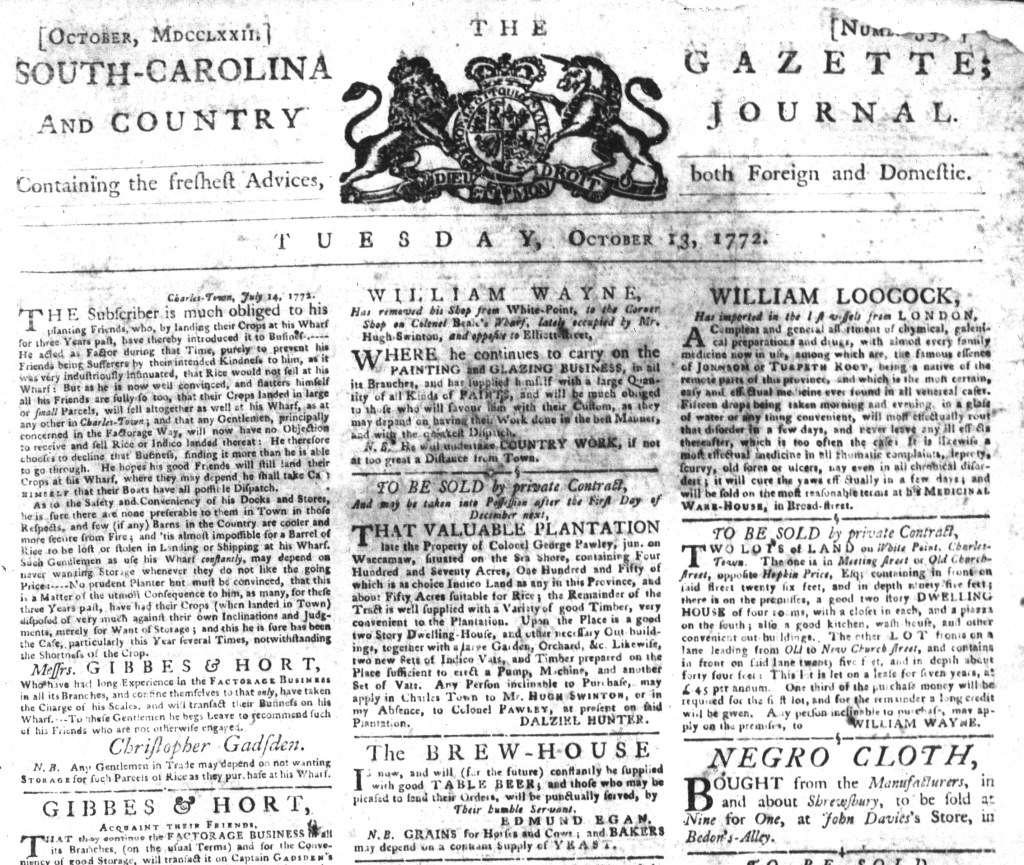

That was not the case for the October 13, 1772, edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal and the Addition that Charles Crouch distributed on the same day. The bulk of the news appeared in the two-page Addition after Crouch devoted ten and a half of the twelve columns in the standard issue to paid notices, including more than a dozen that offered enslaved people for sale or offered rewards for the capture and return of enslaved people who liberated themselves by running away from those who held them in bondage. Paid notices filled the entire first page below the masthead. They also filled the entire third and fourth pages. A short note, “For more London News, see the Addition,” appeared at the bottom of the first column of the second page, the only full column of news. Halfway down the next column, a header for “NEW ADVERTISEMENTS” alerted readers to the content on the remainder of the page.

The two-page Addition gave three times as much space to news compared to the standard issue. News that arrived via London, most of it extracts from letters composed in various cities on the European continent, filled the first page and overflowed onto the second. A short proclamation from the governor of the colony ran as local news midway through the second column on the other side of the sheet. Crouch managed to squeeze in a few more advertisements, including one that promoted a “COMPLETE GERMAN GRAMMAR” that he sold at his printing office. Instead of an advertising supplement that accompanied the newspaper, the Addition amounted to a news supplement that accompanied an advertising leaflet. In many instances, colonial newspapers were vehicles for delivering advertising. That was especially true of the October 13 edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal and its Addition.