What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Dr. KEYSER’s GENUINE PILLS, With FULL DIRECTIONS for their Use in all CASES.”

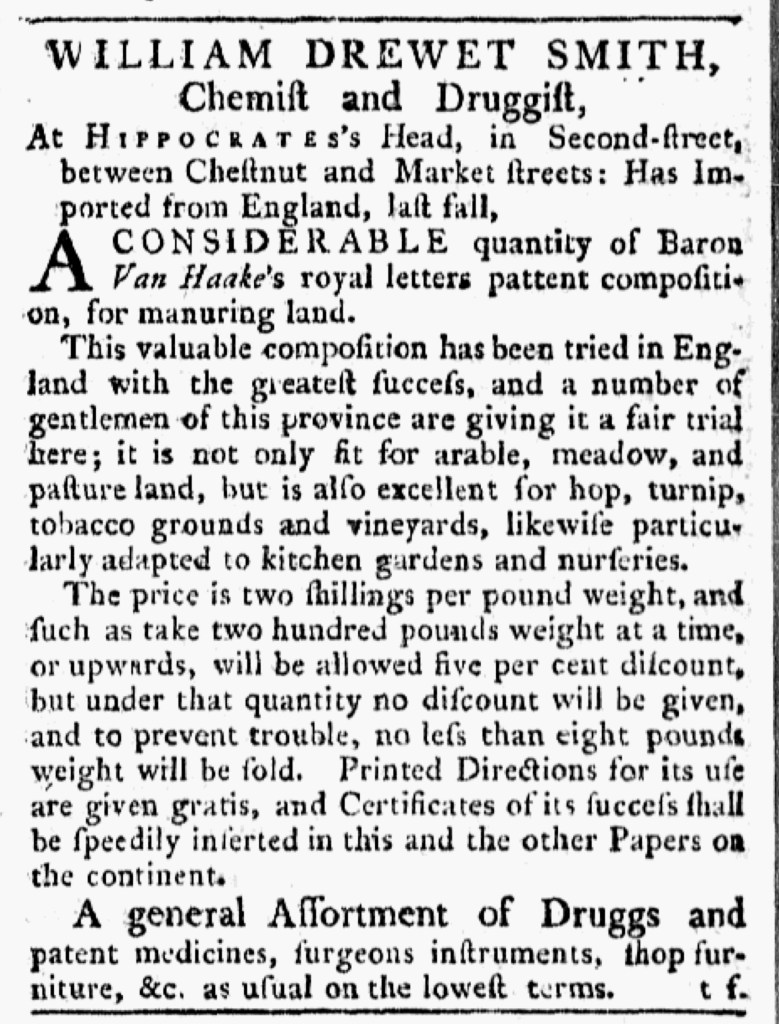

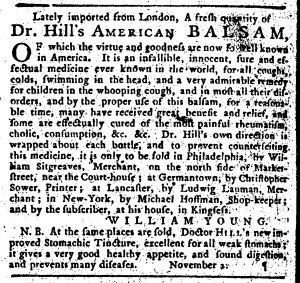

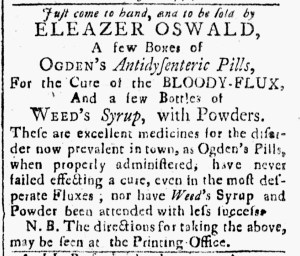

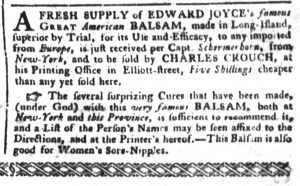

Like many eighteenth-century printers, Charles Crouch, the printer of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, sold patent medicines as a side hustle to supplement revenues from newspaper subscriptions, advertisements, job printing, and selling books and writing supplies. In the May 30, 1775, edition of his newspaper, for instance, he ran an advertisement for a “FRESH PARCEL of Dr. KEYSER’s GENUINE PILLS.” He did not need to explain that the pills treated venereal diseases because they were so familiar to consumers, but that did make it necessary to assure the public that he carried the “GENUINE” item rather than imitations or counterfeits. Crouch also stocked “Dr. BOERHAAVE’s GRAND BALSAM of HEALTH.” Realizing that many prospective customers would have been less familiar with this “admirable Remedy,” the printer explained that they could take it for “the dry Belly-Ach, Cholic, Griping in the Bowels, [and] Pain in the Stomach.” In addition, the balsam “cleanses the Stomach.” Today, many consumers have favorite over-the-counter medicines for similar symptoms.

Crouch realized that treating venereal disease was a sensitive subject and that customers purchasing Keyser’s Pills wanted to use them correctly and effectively. He promised in his advertisement that he provided “FULL DIRECTIONS for their Use in all CASES.” Doing so also minimized the amount of contact between the purchaser and the seller. Customers did not need to visit an apothecary and go over how to use the medication. Instead, they could visit the printer, ask for the pills and the directions, and avoid additional interaction. Some may have even requested Keyser’s Pills along with other items, perhaps ink powder or a recent political pamphlet, to draw attention away from a purchase that caused embarrassment or discomfort. Crouch also assured prospective customers that the pills were effective, inviting them to examine a “NARRATIVE of the Effects of Dr. KEYSER’s MEDICINE, with an Account of his ANALYSIS, by the Members of the Royal Academy of Sciences.” Perusing those accounts did require more interaction between buyer and seller, but Crouch may have believed that some readers would have considered it sufficient to know that they were available. That the printer could provide documentation upon request increased trust in the remedy.

The advertisement for Keyser’s Pills and Boerhaave’s Grand Balsam appeared immediately above a notice listing more than a dozen kinds of printed blanks commonly used for commercial and legal transactions. Beyond publishing the South-Carolina and Country Journal, Crouch generated revenue through a variety of other means, some of them more closely related to printing than others. He could earn money with both printed blanks and patent medicines, especially when he deployed savvy marketing.