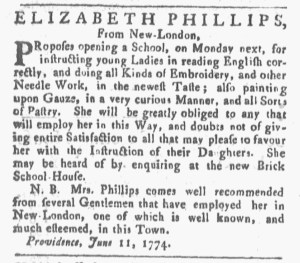

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Mrs. Phillips comes well recommended from several Gentlemen that have employed her in New-London.”

References upon request. That was part of the marketing strategy deployed by Elizabeth Phillips when she relocated from New London to Providence. Upon her arrival in Rhode Island, she placed an advertisement in the Providence Gazette to inform her new neighbors that she “PRoposes opening a School … for instructing young Ladies in reading English correctly, and doing all Kinds of Embroidery, and other Needle Work, in the newest Taste.” Her curriculum also included “painting upon Gauze, in a very curious Manner, and [making] all Sorts of Pastry.” Her pupils learned a variety of feminine arts.

The schoolmistress declared that she “will be greatly obliged to any that will employ her in this Way, and doubts not of giving entire Satisfaction to all that may please to favour her with the Instruction of their Daughters.” Yet the newcomer realized that the public in Providence did not know her and lacked familiarity with her reputation for running a school. Phillips sought to counter that with a nota bene in which she claimed that she “comes well recommended from several Gentlemen that have employed her in New-London.” Parents of prospective students did not have to take her word for it since “one of which is well known, and much esteemed, in this Town.” Phillips did not reveal the identity of this gentleman in the public prints, but readers could learn more “by enquiring at the new Brick School-House.” When they did, that gave the schoolmistress opportunities to share examples of the embroidery and painting she taught in addition to revealing who could speak on her behalf. She likely supposed that engaging with the parents of prospective students in person would garner enrollments just as effectively as recommendations from previous employers, so offering references on request served as a means of initiating those interactions.