What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“By enquiring of Mr. Blake, the Town-Sealer the public may be informed of the quality of his scale beams and steel yards.”

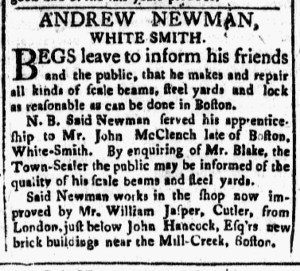

Andrew Newman offered his services as a whitesmith in an advertisement in the March 25, 1773, edition of the Massachusetts Spy. In addition to the usual sort of work undertaken by that trade, such as filing, lathing, burnishing, and polishing iron and steel, Newman declared that he “makes and repair[s] all kinds of scale beams, steel years and lock[s].” Furthermore, he confidently stated that customers would find the quality and prices for such work “as reasonable as can be done in Boston.”

Many artisans included some sort of reference to their credentials, whether formal training or long experience, in their newspaper notices. Newman did so in a nota bene. He advised the public that he “served his apprenticeship to Mr. John McClench late of Boston, White-Smith.” Newman likely hoped that colonizers who previously patronized McClench or were familiar with his reputation would consider hiring McClench’s former apprentice. Even for those who did not know of McClench, Newman figured that giving information about completing an apprenticeship in the city recommended him to prospective customers.

He also encouraged them to consult “Mr. Blake, the Town-Sealer,” for an endorsement. According to Newman, “the public may be informed of the quality of his scale beams and steel yards” when speaking with that local official. Prospective customers did not have to rely on Newman’s word alone; instead, they could learn more and ask questions of a third party that they might consider neutral and thus more trustworthy when it came to assessing the materials that Newman produced and sold. Short of a testimonial inserted in his advertisement, Newman likely considered such referrals the next best option.

Throughout the colonies, artisans often highlighted their credentials in their advertisements. In his efforts to bolster his business, Newman did so, incorporating two strategies. First, he gave details about his apprenticeship, hoping that his training with McClench would resonate with prospective customers familiar with his former master’s work. Then, he directed the public to a local official who could provide an endorsement of Newman’s own skill and the quality of the items he made in his workshop. Invoking both McClench and Black enhanced Newman’s assertions about the quality of his work.