What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“The Introduction to the Royal American Magazine … will be published on the first Day of January next.”

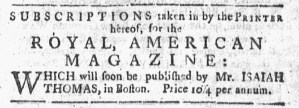

Isaiah Thomas’s efforts to promote the Royal American Magazine in the public prints intensified in November 1773. The Adverts 250 Project has traced his marketing efforts, starting with an announcement, in May, that he would soon publish proposals for the magazine and the first insertion of those proposals in Thomas’s newspaper, the Massachusetts Spy, at the end of June. The printer ran ten advertisements in July, thirteen in August, fourteen in September, twenty in October, and forty-three in November.

The month began with the Boston-Evening Post running Thomas’s “To be, or not to be” update for the first time and the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy carrying it a second time on November 1. Every newspaper then discontinued that notice, likely an acknowledgement of a note at the end of the version in the Boston Evening-Post: “by the appearance of the Subscription Papers in [Thomas’s] possession, there is great probability of [the magazine] going forward.” Three days later, Thomas published an advertisement that appeared only three times, each time in his own Massachusetts Spy. That brief notice called on local agents to send lists of subscribers to Thomas: “THOSE gentlemen, in this and the other provinces, who have subscription papers in their hands for the ROYAL AMERICAN MAGAZINE, are earnestly desired to return them.”

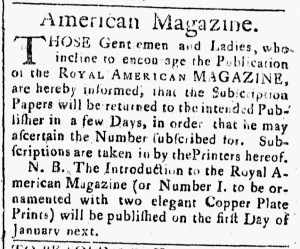

An advertisement that made its first appearance in some newspapers in the final week of October accounted for most of the notices that ran in November. That advertisement advised “gentlemen and ladies, who incline to encourage the publication of the ROYAL AMERICAN MAGAZINE” that “Subscription Papers will be returned to the intended Publisher in a few Days.” That notice ran thirty-two times in November, supplementing its five appearances in October. It became Thomas’s most widely disseminated newspaper advertisement for the proposed magazine. The Maryland Gazette, published in Annapolis, carried the notice four times in November, the first time any of Thomas’s advertisements ran in the public prints that far south. Previously, only newspapers in New England, New York, and Pennsylvania carried it. The Norwich Gazette, a newspaper established in Connecticut in October, also ran the advertisement in late November. It may have featured the advertisement earlier, but the first issues of that newspaper have not survived. This advertisement did not appear in any newspapers published in Massachusetts. Thomas relied on his other advertisements there. Overall, the “Subscription Papers will be returned” advertisement ran in fourteen newspapers published in ten cities and towns in six colonies.

Thomas devised one more advertisement in November 1773. It first appeared in the Massachusetts Spy, but by the end of the month the Boston-Gazette and the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy both heeded Thomas’s plea for “PRINTERS of all the Public Papers in America … to insert this Advertisement.” In it, Thomas stated that the first issue of the Royal American Magazine “will undoubtedly appear on the first of January next.” He solicited essays to include in the new publication. He also made another appeal to prospective subscribers to send their names “if they chuse not to be disappointed” by missing the first issue.

Launching the only magazine published in the colonies at that time was a significant undertaking. That Thomas would eventually take the magazine to press was not inevitable. He needed to cultivate a community of subscribers that extended beyond Boston. To achieve that goal, he devised an extensive advertising campaign, one surpassed only by Robert Bell in his efforts to create an American literary market.

**********

Newspaper Advertisements for November 1773

“To be, or not to be” Update

- November 1 – Boston Evening-Post (first appearance)

- November 1 – Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy (second appearance)

“Subscription Papers will be returned” Update

- November 1 – Newport Mercury (first appearance)

- November 1 – Pennsylvania Chronicle (first appearance)

- November 1 – Pennsylvania Packet (first appearance)

- November 2 – Connecticut Courant (first appearance)

- November 3 – Pennsylvania Journal (first appearance)

- November 4 – Maryland Gazette (first appearance)

- November 4 – New-York Journal (second appearance)

- November 8 – Newport Mercury (first appearance)

- November 8 – New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury (first appearance)

- November 8 – Pennsylvania Chronicle (second appearance)

- November 8 – Pennsylvania Packet (second appearance)

- November 9 – Connecticut Courant (second appearance)

- November 10 – Pennsylvania Gazette (first appearance)

- November 10 – Pennsylvania Journal (second appearance)

- November 11 – Maryland Gazette (second appearance)

- November 11 – New-York Journal (third appearance)

- November 12 – New-Hampshire Gazette (second appearance)

- November 12 – New-London Gazette (second appearance)

- November 15 – Newport Mercury (second appearance)

- November 15 – New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury (second appearance)

- November 15 – Pennsylvania Chronicle (third appearance)

- November 18 – Maryland Gazette (third appearance)

- November 18 – Norwich Packet (first known appearance)

- November 20 – Providence Gazette (first appearance)

- November 22 – New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury (third appearance)

- November 22 – Pennsylvania Chronicle (fourth appearance)

- November 24 – Pennsylvania Gazette (second appearance)

- November 25 – Maryland Gazette (fourth appearance)

- November 25 – Norwich Packet (second appearance)

- November 26 – New-Hampshire Gazette (third appearance)

- November 27 – Providence Gazette (second appearance)

- November 29 – Pennsylvania Chronicle (fifth appearance)

“subscription papers in their hands” Update

- November 4 – Massachusetts Spy (first appearance)

- November 11 – Massachusetts Spy (second appearance)

- November 18 – Massachusetts Spy (third appearance)

“generous Patrons” Update

- November 18 – Massachusetts Spy (first appearance)

- November 22 – Boston-Gazette (first appearance)

- November 22 – Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy (first appearance)

- November 26 – Massachusetts Spy (second appearance)

- November 29 – Boston-Gazette (second appearance)

- November 29 – Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy (second appearance)