What was advertised in a colonial newspaper 250 years ago today?

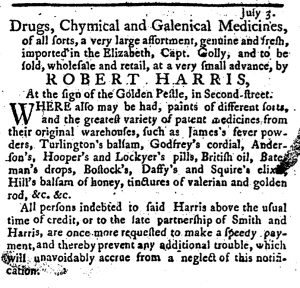

“ROBERT HARRIS, At the sign of the Golden Pestle, in Second-street.”

Not only did a variety of shop signs announce where entrepreneurs operated their businesses, those signs also aided colonists in navigating the streets of cities and towns in an era before street numbers and addresses were either common or standardized. Some shopkeepers and artisans had signs that were memorable and imaginative but did not necessarily correspond to their occupation in any way other than their decision to adopt them as their own logo. For instance, shopkeeper William Murray could be found at the Sign of General Wolfe in Marlborough Street in Boston. Murray’s sign celebrated the British general, a hero of the empire, but in depicting Wolfe it did not reveal what kind of business operated at that location.

Robert Harris, on the other hand, chose a device directly connected to the merchandise he sold. He advertised “Drugs, Chymical and Galenical Medicines, of all sorts,” including an extensive list of popular patent medicines familiar on both sides of the Atlantic. He sold them “At the sign of the Golden Pestle, in Second-street” in Philadelphia. The mortar and pestle were perhaps the equipment most frequently associated with apothecaries in the colonial era, just as they continue to be a recognized symbol and emblem for pharmacists today.

During the second half of the eighteenth century, some colonists used their shop signs in ways that transformed them into what we would today consider a logo that branded their goods and services. They commissioned woodcuts that replicated their shop signs to accompany newspaper advertisements. They distributed trade cards and billheads that also made use of the same images. Robert Harris may not have been quite that innovative when it came to using multiple media and visual images to promote his business, but he was savvy in choosing a sign that unambiguously announced his occupation. This may have been especially imperative in Philadelphia, the largest city in the colonies and an extremely busy port with large numbers of people unfamiliar with the city and its vendors arriving regularly.