What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

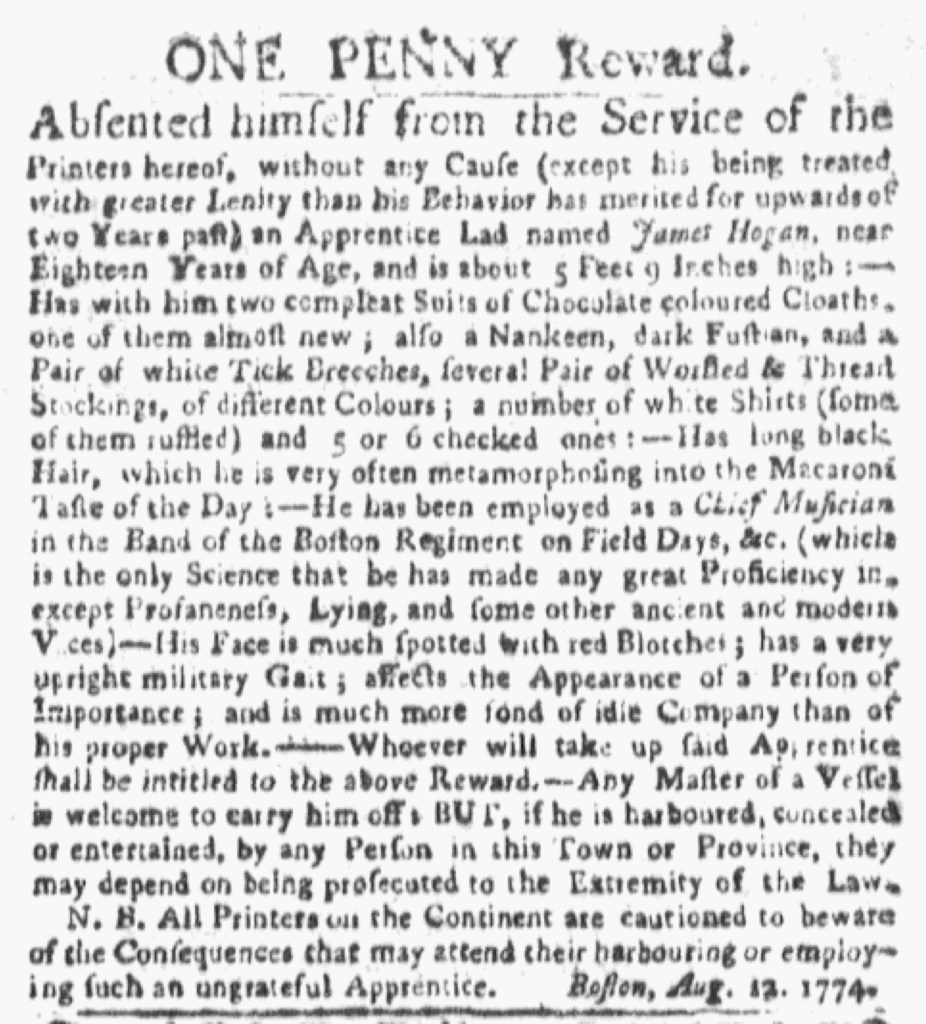

“ONE PENNY Reward.”

Even though they offered a reward, Thomas Fleet and John Fleet, the printers of the Boston Evening-Post, did not really want anyone to return their runaway apprentice to them. The reward, “ONE PENNY,” after all, was hardly an incentive but rather an insult to underscore how much contempt the printers had for James Hogan, their “ungrateful Apprentice.” Contrary to standard language in runaway advertisements that advised ship captains against giving passage to runaway indentured servants and apprentices or enslaved people seeking freedom, the Fleets proclaimed that “Any Master of a Vessel is welcome to carry him off.” They wished to be done with him, while also warning “All Printers on the Continent” against employing Hogan if he found his way to any of their printing offices. Whatever skills he had gained, he was not worth the trouble.

Masters did not always treat apprentices well, yet the Fleets claimed that Hogan absconded “without any Cause (except his being treated with greater Lenity than his Behavior has merited for upwards of two years past).” In addition to working in their shop, Hogan “has been employed as a Chief Musician in the Band of the Boston Regiment on Field Days.” That was the only quality to his credit, “the only Science that he has made any great Proficiency in, except Profaneness, Lying, and some other ancient and modern Vices.” Like too many young men seeking to express themselves and gain attention in a transatlantic consumer society, Hogan put too much emphasis on fashion, one of those vices. According to the fleets, he had “long black Hair, which he is very often metamorphosing into the Macaroni Taste of the Day” and an extensive wardrobe. In describing Hogan as a macaroni, the printers invoked eighteenth-century slang for a dandy or fop, referring in particular to elaborate hairstyles that rose far above the forehead. A print produced in London in June 1774 depicted the dismayed reaction of an “honest FARMER” upon encountering his son, Tom, in all his macaroni trappings, including a wig with hair piled high above his head.

The Fleets suggested that Hogan focused more on this ridiculous fashion than his responsibilities in their printing office. Even though he “has a very upright military Gait” and “affects the Appearance of a Person of Importance,” he was an apprentice who was “much more fond of Idle Company than of his proper Work.” The Fleets did not seem disappointed by his departure. Rather than seek his return, they used their advertisement to denigrate Hogan and warn others against trusting him.