What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

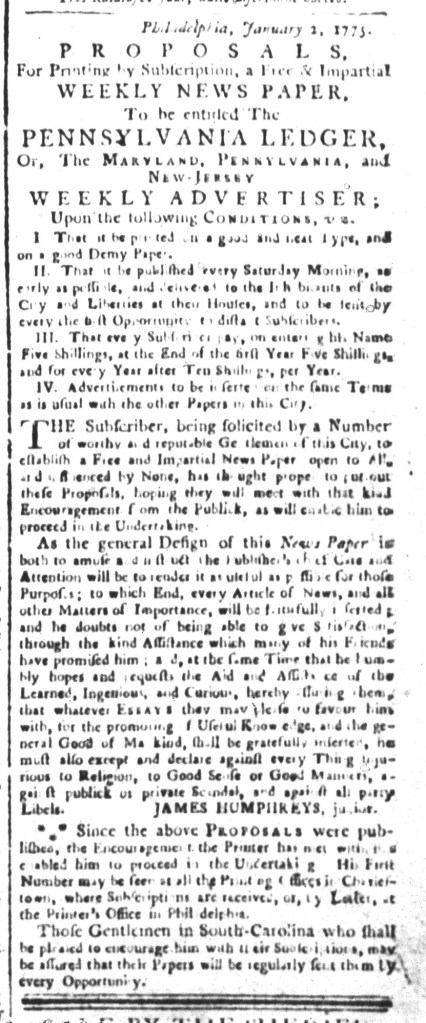

“PENNSYLVANIA LEDGER … His First Number may be seen at all the Printing Offices in Charlestown.”

When James Humphreys, Jr., launched the Pennsylvania Ledger in 1775, he sought local subscribers by placing the proposals for his “Free & Impartial WEEKLY NEWSPAPER” in other newspapers published in Philadelphia. Given the extended title – Pennsylvania Ledger, Or, the Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New-Jersey Weekly Advertiser (in the proposals) or Pennsylvania Ledger: Or the Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New-Jersey Weekly Advertiser (on the masthead) – it made sense to promote the newspaper to prospective subscribers and advertisers in towns in Pennsylvania and neighboring colonies. After all, colonial newspapers served vast regions.

Yet they circulated even more widely than the expansive title of the Pennsylvania Ledger suggested. Realizing that was the case, Humphreys sent the proposals for the Pennsylvania Ledger to R. Wells and Son, the printers of the South-Carolina and American General Gazette, in Charleston. Dated “Philadelphia, January 2, 1775,” the proposals ran in the February 24 and March 3 editions. By that time, Humphreys had already commenced publication of his newspaper. A note at the end of the advertisement acknowledged that was the case: “Since the above PROPOSALS were published, the Encouragement the Printer has met with has enabled him to proceed in the Undertaking. His First Number,” published on January 28, “may be seen at all the Printing Offices in Charlestown, where Subscriptions are received.” Wells and Son acted as local agents for Humphreys, a common practice among eighteenth-century printers who also participated in exchange networks for sharing newspapers and reprinting content.

Another note directed to readers of the South-Carolina and American General Gazette advised, “Those Gentlemen in South-Carolina who shall be pleased to encourage [Humphreys] with their Subscriptions, may be assured that their Papers will be regularly sent them by every Opportunity.” That the January 28 edition was available for inspection at a local printing office by February 24 testified to Humphreys’s commitment to delivering newspapers to distant subscribers in a timely manner. While he certainly welcomed individual subscribers, the printer likely hoped that his newspaper would attract the attention of the proprietors of establishments where merchants and others gathered to do business. Coffeehouses, for instance, often supplied newspapers from near and far for patrons to peruse news about current events and consult the shipping news for updates about commerce in the British Atlantic world. Humphreys had a reasonable expectation that publishing proposals for the Pennsylvania Ledger would yield subscribers in South Carolina.