GUEST CURATOR: Ella Holtman

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

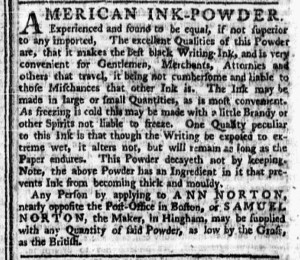

“AMERICAN CAKE-INK.”

This advertisement is extremely interesting because we do not use the term or commonly understand what cake ink is today. As author Harry Schenawolf explains in his Revolutionary War Journal, the Nortons’ cake ink was most likely dried iron gall ink. With a dash of water, the powder became liquid and ready to use with a quill. Iron gall ink is made from a mixture of iron sulfate, oak galls, and tree gum, ensuring it to be long-lasting, adherent, and dark.

Samuel Norton produced his own dried iron gall cake ink. Anna Norton sold it in Boston. They offered their product to any patriotic supporter of America. In the advertisement, the Nortons also reminded the public that their cake ink went for “the same rates as the British Cake-Ink is sold at in London.” They offered an American product for the same prices charged in Britain, obeying a nonimportation agreement. This alludes to the growing tension between the American colonies and Britain’s perceived unjust control in February 1775.

When the Revolutionary War started a couple of months later, American soldiers went to fight, bringing few belongings and facing long travels. Officers and soldiers easily transported and utilized cake ink. They wrote home to loved ones and shared news. Purchasing and using cake ink, like that made and sold by the Nortons, aided in communication during the era of the American Revolution.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

As Ella notes, the Nortons advertised their cake ink at an important moment. The Boston Port Act closed the city’s harbor on June 1, 1774, severely hampering commerce. In response, the colonies enacted the Continental Association, a nonimportation agreement, on December 1. In addition to boycotting imported goods, the Continental Association called on colonizers to “encourage Frugality, Economy, and Industry; and promote Agriculture, Arts, and the Manufactures of this Country.”

The Nortons did just that when they marketed “AMERICAN CAKE-INK” to “all true friends to America.” They did so at a time when other advertisers also advanced “Buy American” messages or otherwise indicated their compliance with the Continental Association. Consider some of the advertisements that ran alongside the Nortons’ notice in the February 2, 1775, edition of the Massachusetts Spy. Henry Christian Geyer advertised printing ink that he “manufactured … at his Shop near Liberty Tree” in Boston’s South End. A nota bene indicated that the Massachusetts Spy “has been printed with Ink made by said Geyer, for two months past.” A similar nota bene appeared in his advertisement in the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy. Enoch Brown’s notice sporting the headline “American Manufacture” ran once again, offering textiles produced in Massachusetts and glassware “manufactured at Philadelphia” as alternatives to imported goods. Philip Freeman inserted an advertisement for gloves that had been running for six months, lamenting the “threatening” times and asking consumers to “encourage our own Manufactures” by purchasing the gloves that he made. In a relatively new advertisement, John Clarke hawked the buttons that he produced “at the Manufactory-house, Boston,” each inscribed, “UNION AND LIBERTY IN ALL AMERICA.” Another advertisement notices announced the sale of “SUNDRY Goods … imported in the Brigantine Venus … from London” conducted under the supervision of the local Committee of Inspection according to the provisions of the tenth article of the “American Congress Association.”

The short advertisement for “AMERICAN CAKE-INK” that Ella selected for today’s entry played its part in disseminating messages about leveraging decisions about consumption to achieve political ends, especially when considered in concert with several other advertisements in the same issue of the Massachusetts Gazette. Consumers, these notices reminded readers, participated in politics when they chose which items purchase.