What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“The Advertiser once had a small Sign of a Sugarloaf affixed to his little Shop.”

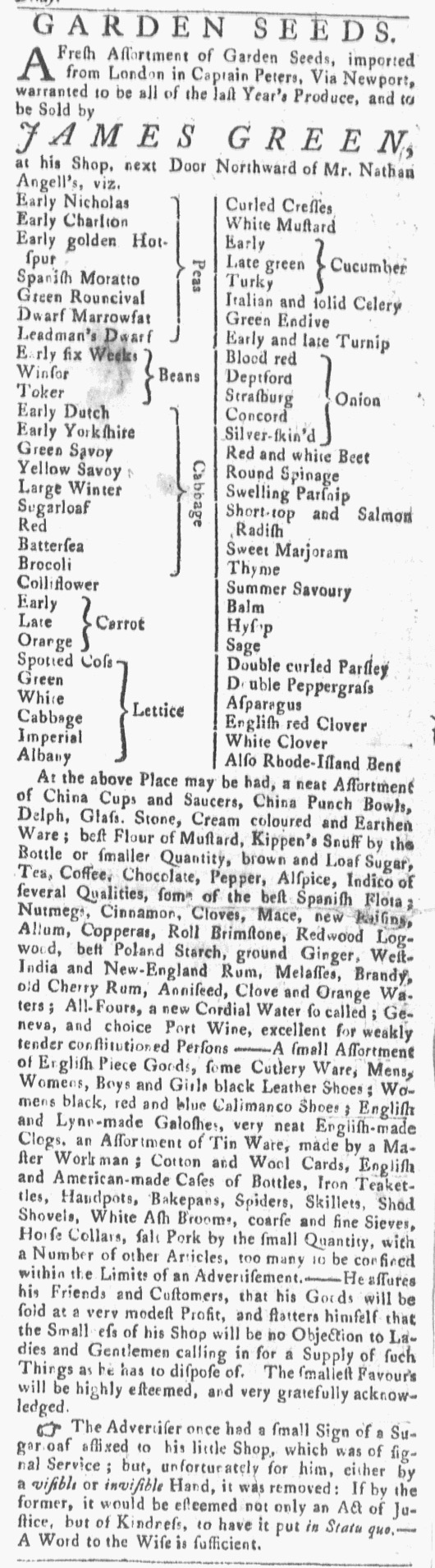

As spring approached in 1774, advertisements for “GARDEN SEEDS” appeared in newspapers in New England. John White was the first to advertise in Boston, soon joined by Susanna Renken, Elizabeth Clark, Elizabeth Greenleaf, Elizabeth Nowell, and other women who annually announced they sold seeds in the city’s newspapers. As Abel Buell hawked firearms in the Connecticut Journal, Nathan Beers promoted “Garden Seeds, Both of English and American Growth.” In Rhode Island, James Green placed an extensive advertisement for a “Fresh Assortment of Garden Seeds” in the Providence Gazette, as he had done the previous year. The format distinguished it from other notices, the various types of peas, beans, cabbage, carrot, lettuce, cucumber, and onion clustered together and labeled by category.

Unlike most other seed sellers, Green also marketed all sorts of housewares, garments, and groceries in his advertisement. That significantly contributed to the length of a notice that extended more than two-thirds of a column. Green stocked everything from “a neat Assortment of China Cups and Saucers” and “Womens black, red and blue Calimanco Shoes” to “best Four of Mustard” and “Kippen’s Snuff by the Bottle or smaller Quantity.” Yet that was not all. He asserted that his inventory included “a Number of other Articles, too many to be confined within the Limits of an Advertisement.” A newspaper notice could not contain all the choices Green made available to consumers! The shopkeeper also made an appeal to price, “assur[ing] his Friends and Customers, that his Goods will be sold at a very modest Profit.” Conversationally, he confided that he “flatters himself that the Smallness of his Shop will be no Objection to Ladies and Gentlemen calling in for a Supply of such Things he has to dispose of.”

All of that was standard for advertisements in newspapers published throughout the colonies. A final note, however, discussed unusual circumstances that agitated the shopkeeper. “The Advertiser once had a small Sign of a Sugarloaf affixed to his little Shop,” Green noted. In marking his location, it “was of signal Service.” Yet the sign no longer adorned his shop: “unfortunately for him, either by a visible or invisible Hand, it was removed.” Perhaps bad weather, an “invisible Hand, had carried it away, but if that was not the case, if some prankster had taken it then Green petitioned for its return: “it would be esteemed not only an Act of Justice, but of Kindness, to have it put in Status quo.” Using an eighteenth-century version of “no questions asked,” he declared that “A Word to the Wise is sufficient.” If anyone knew what had happened to the sign, he hoped that they would encourage whoever had it to put it back where it belonged. Green was not interested in the details of where his sign had been or who took it, only its return to its rightful place as the emblem designating his place of business. The shopkeeper made an aside in his newspaper advertisement to tend to other forms of marketing associated with his shop in Providence.