What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

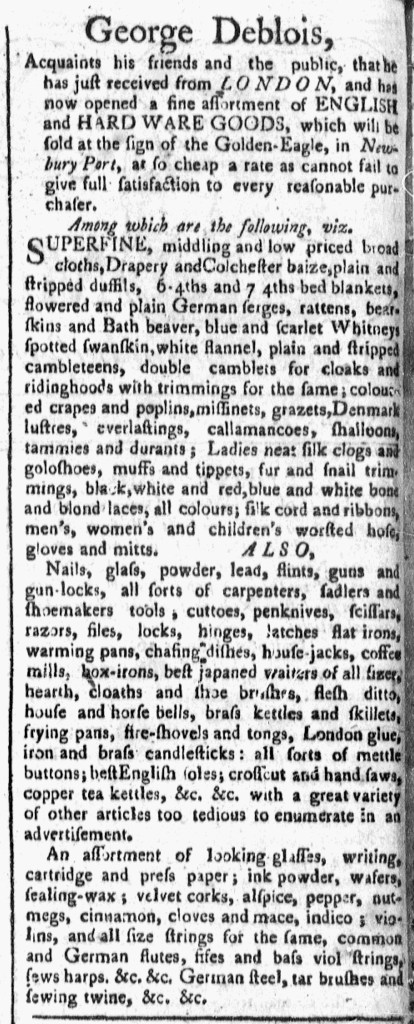

“The Sign of the GOLDEN EAGLE.”

In an era before standardized street numbers, colonizers used a variety of methods for giving directions and marking locations. For instance, the colophon for the Essex Gazette noted that Ezra Lunt and Henry-Walter Tinges ran their printing office in “KING-STREET, opposite to the Rev. Mr. PARSONS’s Meeting-House” in Newburyport. Some of the advertisements in the March 15, 1775, edition of their newspaper also gave directions in relation to other locations. Robert Fowle, a stonecutter from Boston, advised prospective customers that he now had a workshop “next to Mr. Jonathan Titcomb’s store, near Somersby’s Landing,” places that he believed were familiar to local readers. John Vinal ran a school “nearly opposite Mr. Davenport’s Tavern.” Thomas Mewse gave even more elaborate directions to the site where he “CUTS Stamps and prepares a Liquid for Marking” textiles with the names of the owners, stating that he “may be spoke with at Mr. Jacksons, next door to Dr. Coffin’s, in Rogers’s-street, Newbury-Port.”

Another advertiser relied on a shop sign to mark the location where customers could purchase “English CHEESE,” “A good Assortment of English and Piece Goods, Iron-mongery, Cutlery and Braziery Ware,” and other merchandise: “the Sign of the GOLDEN EAGLE, Near the Court House.” References to shop signs did not appear in advertisements in the Essex Journal as often as in advertisements inserted in newspapers published in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, in part because that newspaper carried fewer paid notices than the others. In addition, Newburyport was a smaller town with fewer businesses that relied on such devices to mark their locations. Yet an advertisement that directed readers to “the Sign of the GOLDEN EAGLE” demonstrates that shop signs became part of the visual culture that colonizers encountered as they traversed the streets of smaller ports, not just major urban centers. Few shop signs from the colonial era survive today. Newspaper advertisements testify to the existence of this method that merchants, shopkeepers, and artisans used to establish commercial identities and mark their locations.