What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

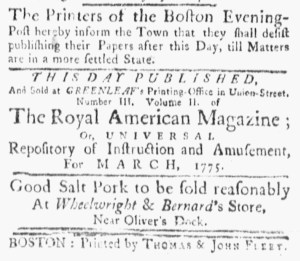

“They shall desist publishing their Papers after this Day, till Matters are in a more settled State.”

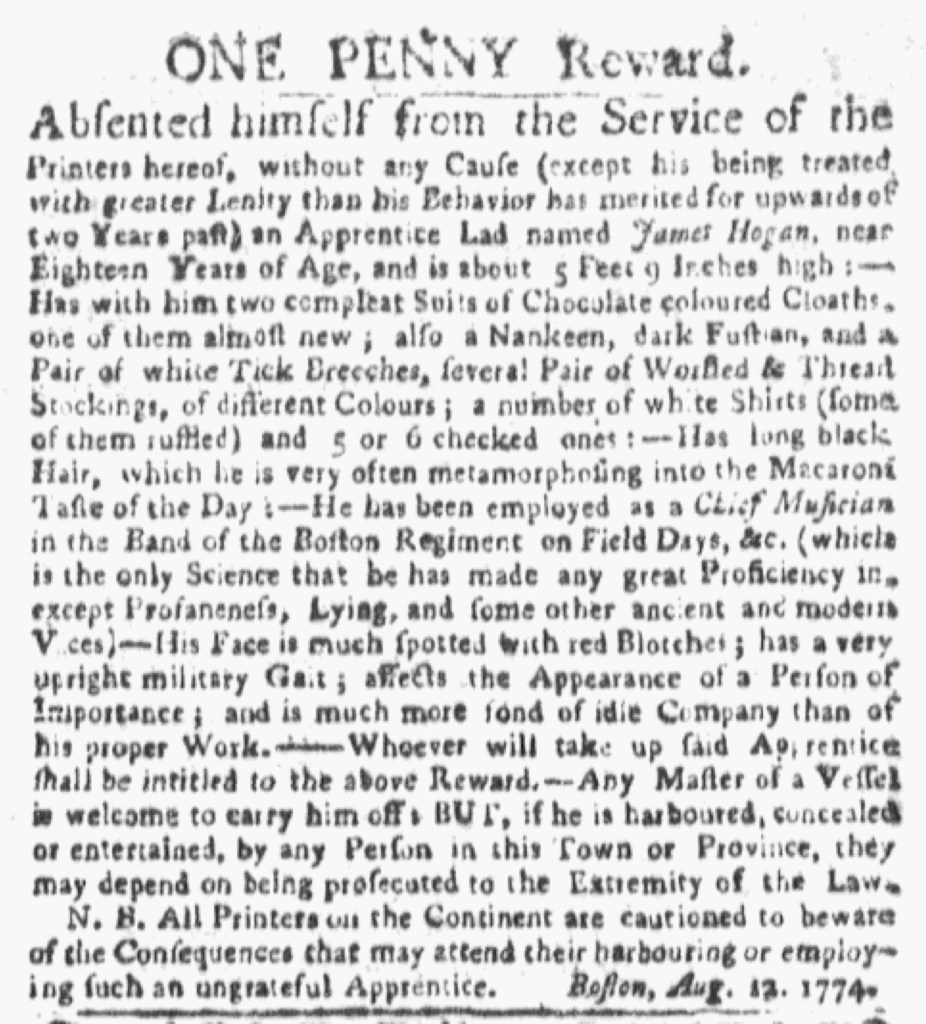

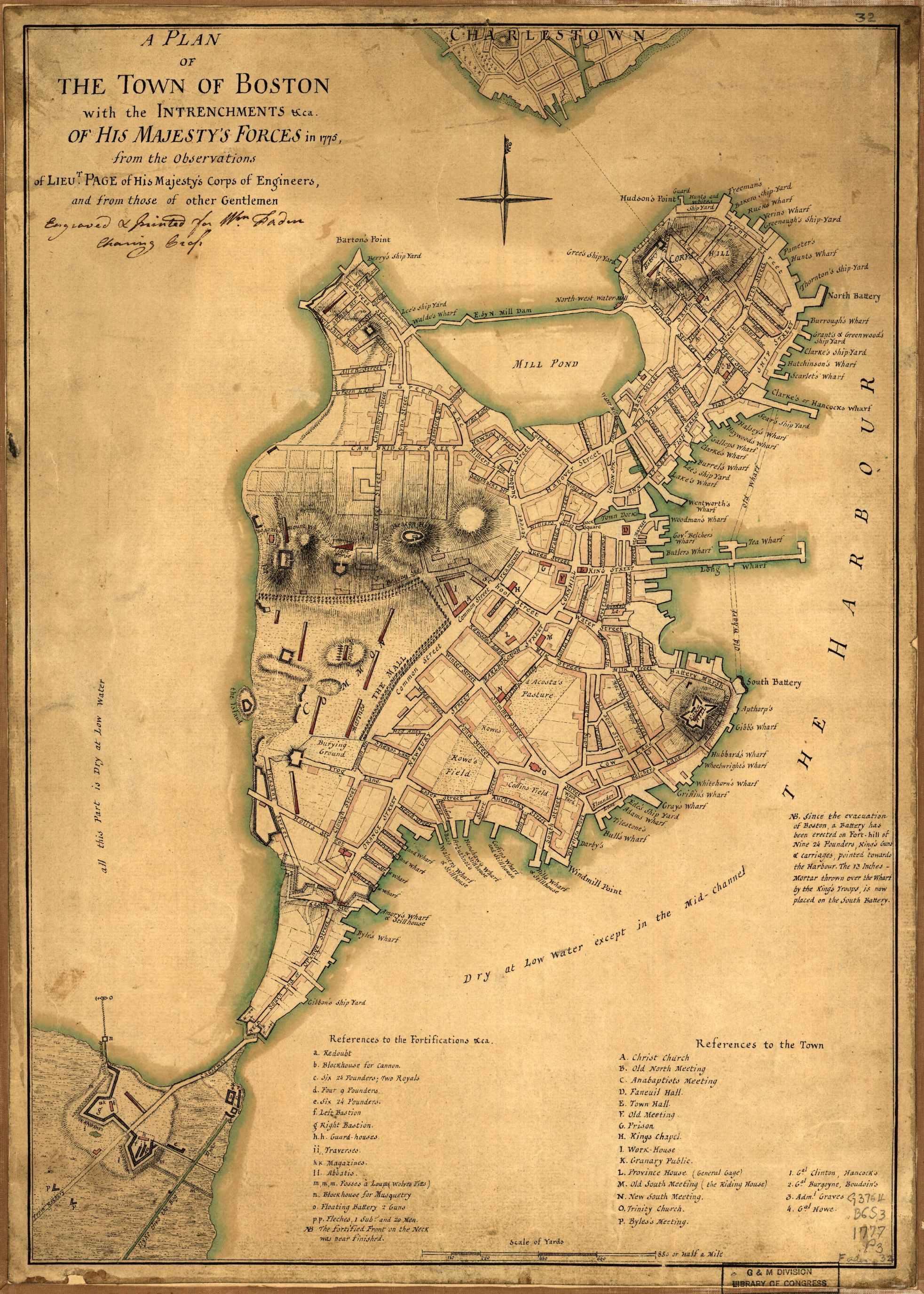

The printers and the public did not know it yet, but the April 24, 1775, edition of the Boston Evening-Post would be the last issue of that newspaper. Thomas Fleet established the newspaper in August 1735. His sons, Thomas and John, continued publishing the Boston Evening-Post after their father’s death in 1758. They even disseminated issues while the Stamp Act was in effect from November 1765 through May 1766, though they did not include their names in the colophon. The events at Lexington and Concord, however, were too much of a disruption to continue. The Fleets initially intended to suspend the newspaper and continue publication at some point in the future. The April 24 issue included only three advertisements, the first one from the printers to “inform the Town that they shall desist publishing their Papers after this Day, till Matters are in a more settled State.” A newspaper that had served Boston for just shy of forty years ended with “NUMB. 2065.”

By that time, Isaiah Thomas, the printer of the Massachusetts Spy, had already published the final issue of that newspaper in Boston on April 6 and headed to Worcester. He revived it as the Massachusetts Spy: Or, American Oracle of Liberty in early May. Nathaniel Mills and John Hicks distributed the last known issue of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy on April 17. The April 20 edition of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter was the last for a month. Margaret Draper and John Boyle resumed publication of that newspaper on May 19, though they published issues sporadically for the next several months before turning the newspaper over to John Howe. The February 29, 1776, edition may have been the last; it is the last known issue. Benjamin Edes and John Gill suspended the Boston-Gazette with the April 17, 1775, edition. Edes went to Watertown and resumed publication there on June 5. He remained in Watertown until the end of October 1776. At that time, he returned to Boston and continued publication in November. His sons became partners in 1779. The Boston-Gazette did not close until September 1798.

At the beginning of April 1775, five newspapers served Boston, yet the beginning of the Revolutionary War in nearby Lexington and Concord on April 19 had a dramatic impact on those newspapers. Two folded immediately, even though they hoped to resume when “Matters are in a more settled state.” One suspended publication for a month and then limped along for less than a year. Another relocated to Worcester and experienced success there. Only the Boston-Gazette survived the war and resumed publication in that city. Other newspapers eventually filled the void, commencing publication during the war, but for some time the town that long had more newspapers than any other in the colonies adapted to new circumstances that limited publication of news (and advertisements).