What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Hope the Customers to the Paper will continue to encourage it by advertising.”

The first advertisement in the April 26, 1773, edition of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy concerned the operation of the newspaper. For nearly sixteen years, since August 1757, John Green and Joseph Russell printed the newspaper, but starting on that day “the Printing and Publishing of this PAPER will, in future be carried on by NATHANIEL MILLS and JOHN HICKS.” Neither the printers nor readers knew it at the time, but the newspaper would not continue for nearly as long under Mills and Hicks. They published the last known issue on April 17, 1775, two days before the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord that marked the beginning of the Revolutionary War.

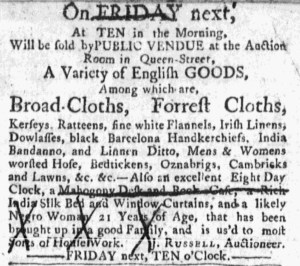

At the time that ownership of the newspaper changed hands, Green and Russell expressed “their respectful Thanks for the Favours they have received.” Furthermore, they expressed their “hope the Customers to the Paper will continue to encourage it by advertising, &c.” That “&c.” (an abbreviation for et cetera) included subscribing to the newspapers and providing content, such as editorials and “Letters of Intelligence.” The printers realized that the continued viability and success of the newspapers depended most immediately on maintaining advertising revenue since readers but subscribed for a year while most advertisements ran for only three or four weeks.

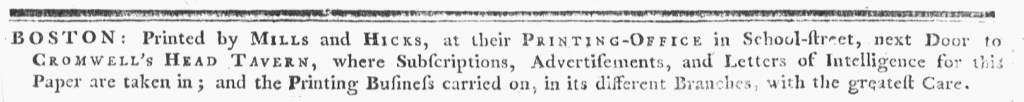

Readers likely noticed a new feature in the first issue published by Mills and Hicks, a colophon that ran across the bottom of the final page. Green and Russell did not always include a colophon, perhaps because they considered the newspaper so well established that they did not consider it necessary to devote space to it in each issue. Their final issue, the April 19 edition, for instance, did not feature a colophon. On April 12, the colophon at the bottom of the last column on the final page simply stated, “Printed by Green and Russell.” Mills and Hicks, on the other hand, opted for a more elaborate colophon that served as a perpetual advertisement for the newspaper and other services available in their printing office, a practice adopted by some, but not all, colonial printers. Distributed over three lines, it read, “BOSTON: Printed by MILLS and HICKS, at their PRINTING-OFFICE in School-street, next Door to CROMWELL’S HEAD TAVERN, where Subscriptions, Advertisements, and Letters of Intelligence for this Paper are taken in; and the Printing Business carried on, in its different Branches, with the greatest Care.”

Mills and Hicks could not depend on their reputations to market the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy in the same way that Green and Russell did after more than a decade of publishing the newspaper. In their first issue, they placed greater emphasis on soliciting advertisements to help support their enterprise. Subsequent issues included the colophon, a regular feature that encouraged colonizers to advertise as well as purchase subscriptions and submit orders for job printing.