What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Gentlemen in the army … forwarding their commands by any of the post-riders, may depend on fidelity and dispatch.”

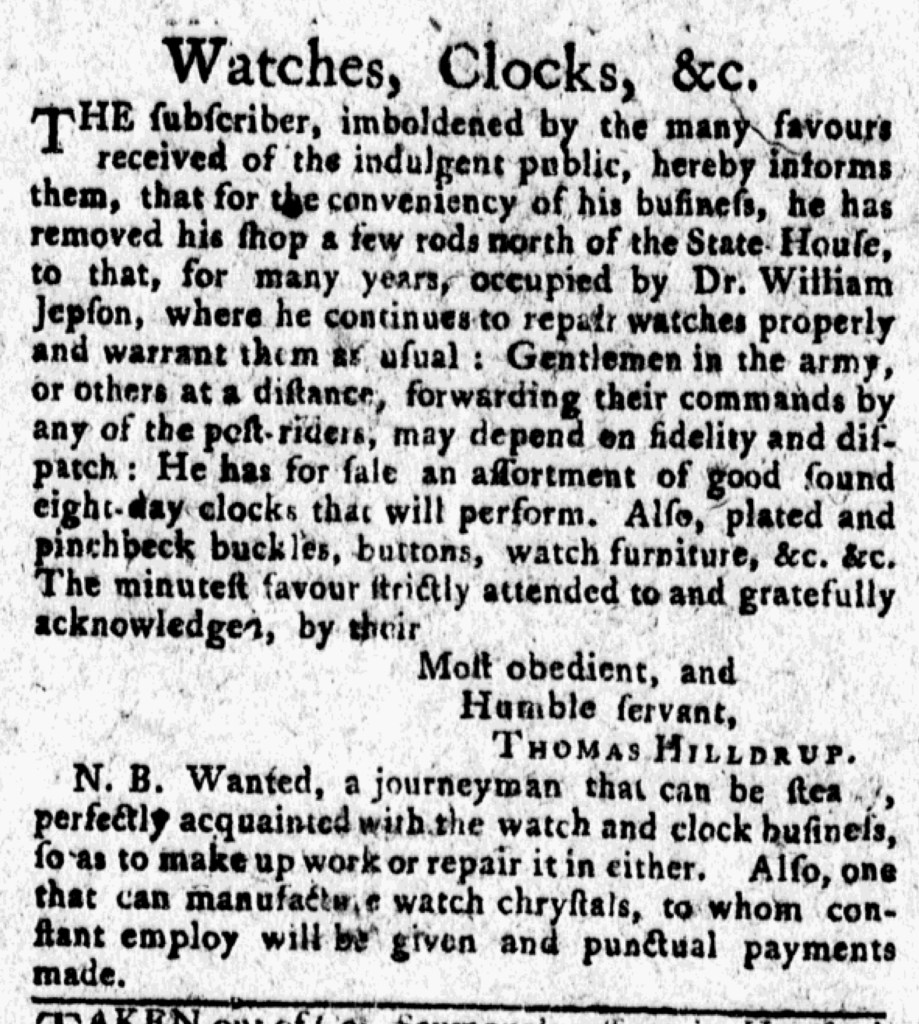

Thomas Hilldrup, a watch- and clockmaker, had a history of running engaging advertisements in newspapers printed in Connecticut in the 1770s. He once again took to the pages of the Connecticut Courant and Hartford Weekly Intelligenceron December 18, 1775, this time informing existing and prospective clients that he had moved to a new location. In framing this announcement, he asserted that he had already built a reputation and earned the trust of many customers. Having been “imboldened by the many favours received of the indulgent public,” Hilldrup declared, he “hereby informs them that for the conveniency of his business, he has removed his shop a few rods north of the State-House, to that, for many years, occupied by Dr. William Jepson.” He supplemented this announcement with assurances about his skill and the quality of his work, stating that he “continues to repair watches properly and warrant them as usual.”

Realizing that the Connecticut Courant circulated far beyond Hartford, Hilldrup took the opportunity to address “Gentlemen in the army, or others at a distance.” Like other watchmakers, he provided mail order services for cleaning and repairs. He promised those clients that by “forwarding their commands by any of the post-riders” they “may depend on fidelity and dispatch.” As the Continental Army continued the siege of Boston, Hilldrup may have known that some of the clients he served in recent years too part in that endeavor. In an unfamiliar place that experienced some of the most significant disruptions during the first year of the Revolutionary War, they may have been at a loss to identify local artisans that they trusted to do repairs and perform routine maintenance. That might have made Hilldrup’s mail order service look especially attractive. The watchmaker likely also hoped that others enlisted in the army (as well as “others at a distance”) who had not previously availed themselves of his services would be influenced by his claim that he already established a robust clientele, those “many favours received of the indulgent public” that he invoked at the beginning of his advertisement. Whether or not this strategy proved effective, Hilldrup envisioned “Gentlemen in the army” as a new category of customers to target in his marketing. The Revolutionary War presented opportunities to savvy entrepreneurs as well as challenges and disruptions.