What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

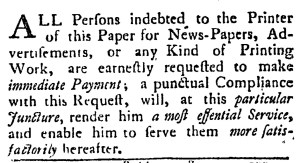

“ALL Persons indebted to the Printer … are earnestly requested to make immediate Payment.”

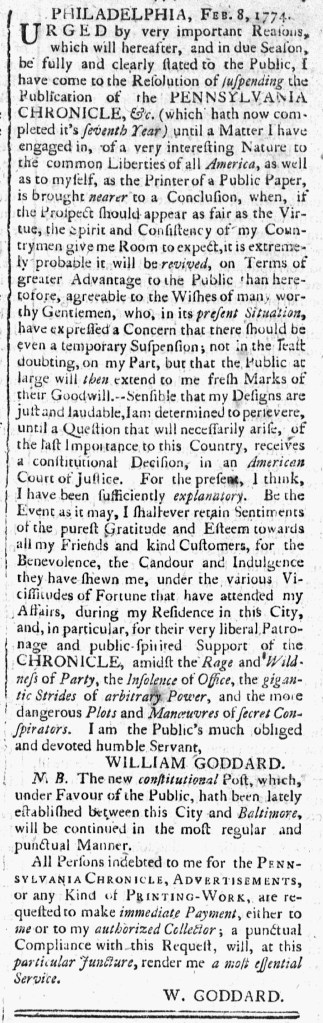

Among the advertisements that filled the first page of the January 9, 1775, edition of the Maryland Gazette, William Goddard inserted his own notice that requested “ALL Persons indebted to the Printer of this Paper for News-Papers, Advertisements, or any Kind of Printing Work … make immediate Payment.” Printers often placed such notices calling on subscribers to settle accounts and, sometimes, incorporating overdue payments for other services.

The inclusion of “Advertisements” in Goddard’s notice raises questions about the business model usually associated with colonial printers. Historians of the early American press have long asserted that printers extended credit for subscriptions while demanding payment in advance for advertisements. Accordingly, advertising represented the real revenue in publishing newspapers. Yet several printers periodically called on customers to pay for “Advertisements.” Those notices, however, do not make clear what they meant by “Advertisements.” They may have referred to paid notices that appeared in their newspapers, in which case some printers deviated from the (standard?) practice of requiring payment in advance, but they might have instead meant handbills, broadsides, and other advertising media that many printers stated that they could prepare on short notice.

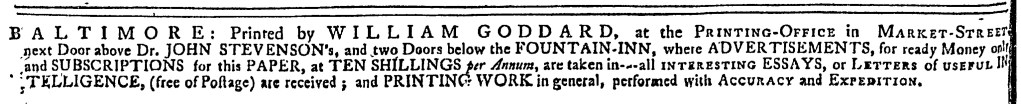

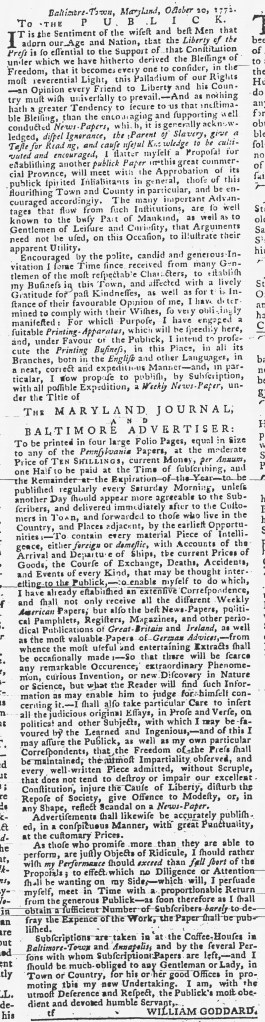

In the colophon at the bottom of the final page, Goddard gave the location of his printing office in Baltimore, “where ADVERTISEMENTS, for ready Money only, and SUBSCRIPTIONS for this PAPER … are taken in.” That suggests that Goddard did indeed have a policy of insisting on payment for advertisements before printing them in the Maryland Journal. Does that definitively mean that “Advertisements” in his call for customers to pay their bills meant handbills and broadsides and not newspaper notices? Not necessarily. Goddard may have invoked a relatively new policy. The colophon that asserted that he inserted advertisements “for ready Money only” had been in use for about three months, since October 1774, but prior to that he had used a streamlined version that did not mention any of the services he provided. In its entirety, it read: “BALTIMORE: Printed by W. GODDARD, at his Printing-Office near the FOUNTAIN-INN, MARKET-STREET.” Perhaps Goddard previously extended credit to advertisers but changed his policy when too many took advantage. His notice and his colophons do not give a straightforward answer but instead suggest that the business practices of some printers may have been more complex than often assumed.