What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

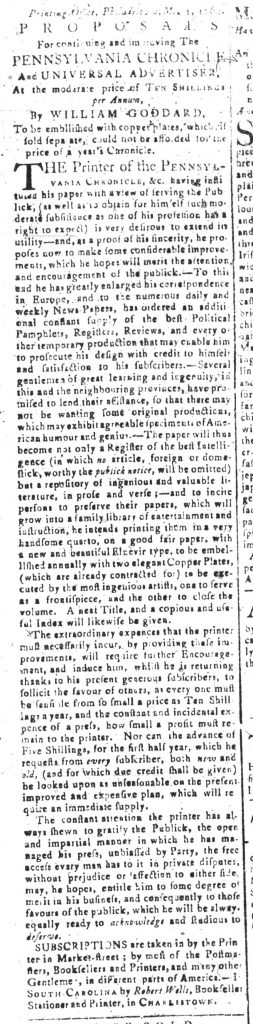

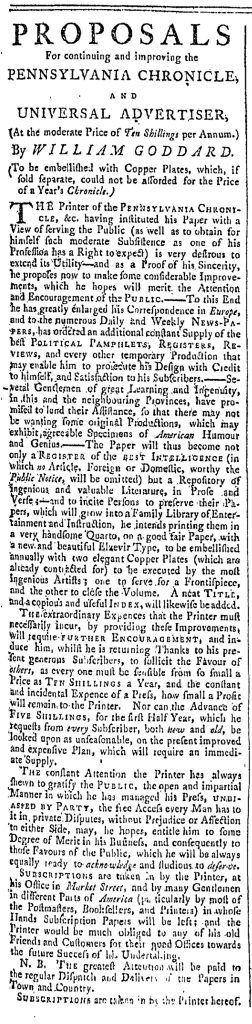

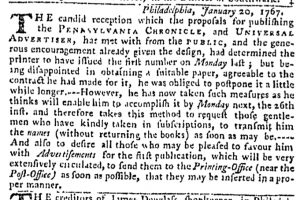

“PROPOSALS FOR CONTINUING AND IMPROVING The PENNSYLVANIA CHRONICLE.”

In the spring of 1769, William Goddard launched an advertising campaign intended to garner subscriptions for the Pennsylvania Chronicle from throughout the colonies. In outlining its contents, Goddard described a weekly publication that prospective subscribers may have considered as much a magazine as a newspaper. He proclaimed, “Several Gentlemen of great learning and ingenuity, in this and the neighbouring provinces, have promised to lend their assistance, so that there may not be wanting dome original productions, which may exhibit agreeable specimens of American humour and genius.” That being the case, Goddard did not produce a local or regional newspaper that merely delivered news reprinted from one newspaper to another, but instead a “Repository of ingenious and valuable literature, in prose and verse.” Goddard intended for subscribers to preserve their copies of the Pennsylvania Chronicle, pledging to distribute a title page, index, and two copperplate engravings (one for use as a frontispiece) to be bound together with the several issues each year. Such plans paralleled those distributed by magazine publishers in eighteenth-century America.

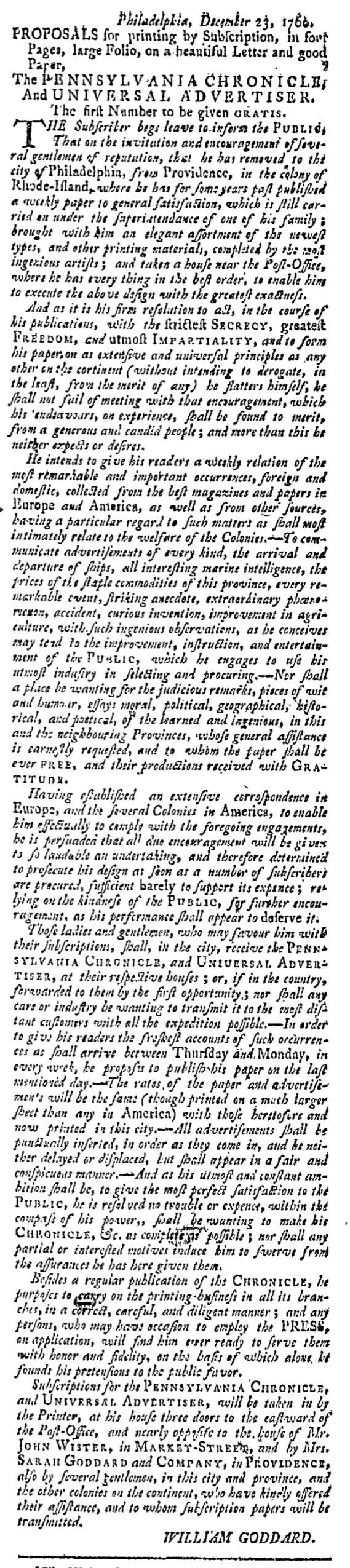

Goddard’s “PROPOSALS FOR CONTINUING AND IMPROVING The PENNSYLVANIA CHRONICLE” radiated out from Philadelphia. They first found their way into newspapers published in New York and then others published in New England. Eventually they appeared in newspapers published in southern colonies. Dated “May 1, 1769,” Goddard’s “PROPOSALS” did not run in the Georgia Gazette, the newspaper most distant from Philadelphia, until July 19, eleven weeks later. Goddard envisioned what Benedict Anderson termed an imagined community of readers. Although dispersed geographically, readers formed a sense of community and common interests through exposure to the same information via print culture. Colonial newspapers served this purpose as printers established networks for exchanging their publications and liberally reprinting news and other content from one to another. Goddard presented an even more cohesive variation: subscribers throughout the colonies reading the same information in a single publication and feeling a sense of community because they knew that other subscribers in faraway places read the same news and literature contained in the Pennsylvania Chronicle, rather than whichever snippets from other publications an editor happened to choose to reprint for local and regional consumption.

Creating an imagined community depended in part on establishing a sense of simultaneity, that readers were encountering the same content at the same time. Communication and transportation technologies in the eighteenth century made true simultaneity impossible, as seen in the lag between Goddard composing his “PROPOSALS” on May 1 and their eventual publication in the Georgia Gazette on July 19. Yet readers could experience a perceived simultaneity from knowing that they read the same publication as subscribers in other colonies. Reprinting items from one newspaper to another already contributed to this, but the widespread distribution of a single publication made that perceived simultaneity much more palpable and certain. Readers encountered Goddard’s “PROPOSALS” in several newspapers published in cities and towns throughout the colonies, but they could experience the same contents, pitched as political and cultural and distinctively American, in the pages of the publication that Goddard made such great effort to distribute as widely as possible.