What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“A Paper of as good Credit and Utility as any extant.”

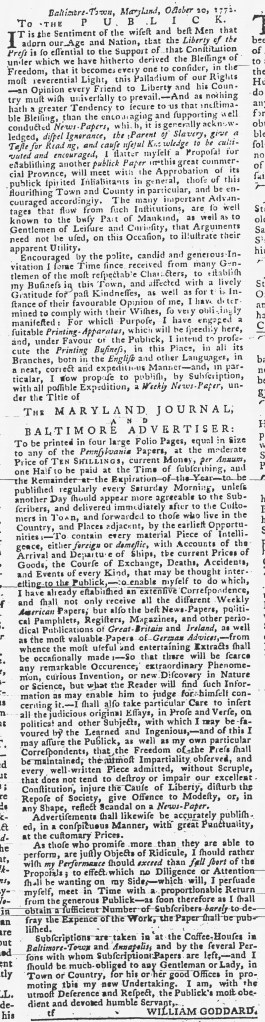

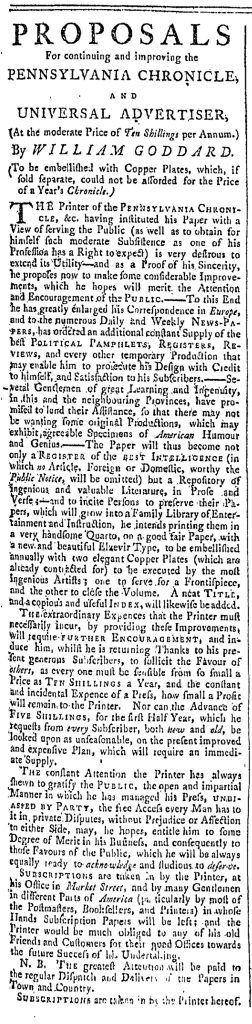

An advertisement address to “the respectable Publick” informed readers of the New-York Journal that Samuel F. Parker and John Anderson “entered into Partnership together … and propose in August next, to publish the New-York Gazette, or the Weekly Post Boy.” The newspaper, founded as the New-York Weekly Post-Boy in 1743, had a long history in the city.

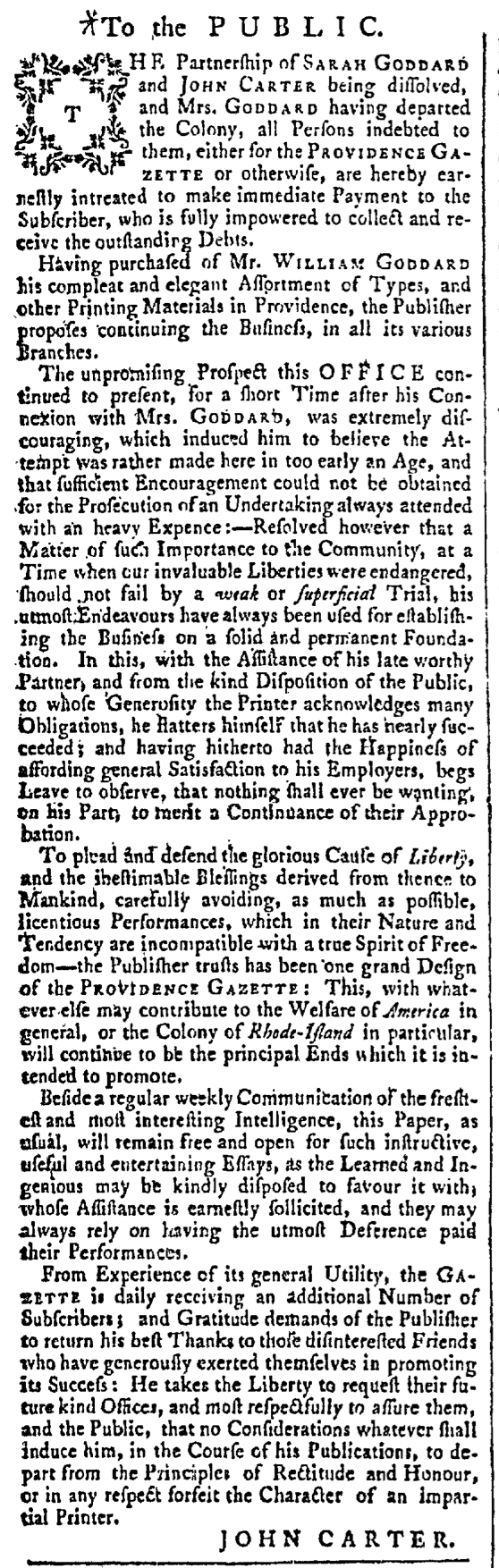

James Parker, great-uncle to Samuel F. Parker, established the newspaper, took William Weyman into partnership in 1753, and dissolved the partnership one week before retiring in 1759.[1] At that time, his nephew, Samuel Parker, continued the newspaper, taking John Holt into partnership the following year. When Parker and Holt dissolved their partnership in 1762, Holt became the publisher of the newspaper. According to Isaiah Thomas, the newspaper “appeared in mourning on the 31st of October, 1765, on account of the stamp act; it was, however, carried on as usual, without any suspension, and without any stamps.”[2] When Parker wished to resume printing a newspaper in 1766, Holt opted to adopt a new title, the New-York Journal, and continued the volume numbering of the New-York Gazette or Weekly Post-Boy. Parker regained that title and resumed publication in October 1766, also continuing the volume numbering. Upon Parker’s death in 1770, Samuel Inslee and Anthony Car leased the newspaper from his son, Samuel F. Parker, and printed it until the end of their lease in August 1773.

Parker and Anderson anticipated the conclusion of that lease. While they likely did not expect the public to know all the details of the newspaper’s publication history, they did believe that many readers would have been familiar with Parker’s father and the reputation of the newspaper as “a Paper of as good Credit and Utility as any extant since the first Commencement thereof.” They intended to continue that tradition “by every possible Means” and pledged to deliver “especial Service [for] the Commercial Interest.” In addition to publishing shipping news, prices current, and other content for the benefit of merchants, they also planned to provide for “the Amusement and Information of private Families in Matters both Foreign and Domestick.” Amid the debates of the period, Parker and Anderson promised “free Access to all Parties without Distinction.” In other words, they did not intend to operate a partisan press but instead welcomed “Pieces directed to the Proprietors” as long as the “Subject Matter” was “consistent, and within due Bounds to admit of Publication.”

Such lofty goals, however, did not meet with success. Parker and Anderson published the New-York Gazette or Weekly Post-Boy for a few weeks in August and September 1773. They may have continued the newspaper into November, but no issues bearing their imprint have been identified. On December 9, Anderson ran an advertisement in Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer that announced the partnership had dissolved and called on “all persons that may have any demands against said partnership [to] bring in their accompts and receive payment.” Anderson also noted that he “continues carrying on the Printing-Business in all its branches.” Despite the difficulty he experienced with the New-York Gazette or Weekly Post-Boy, Anderson launched another newspaper, the Constitutional Gazette, in August 1775. It lasted thirteen months, folding when the British occupied New York in September 1776.[3]

**********

[1] Unless otherwise noted, the details of the publication history come from the entries for the New-York Gazette, or Weekly Post-Boy (635-6) and New-York Weekly Post-Boy (704) in Clarence S. Brigham, History and Bibliography of American Newspapers, 1690-1820 (Worcester, Massachusetts: American Antiquarian Society, 1947).

[2] Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America: With a Biography of Printers and an Account of Newspapers (1810; New York: Weathervane Books, 1970), 494.

[3] See the entry for the Constitutional Gazette in Brigham, History and Bibliography of American Newspapers, 618.