What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“At their Shop, the Sign of the Golden Eagle, near the Court-House. (23).”

Joseph and William Russell’s advertisement for “A most neat and general Assortment of SPRING and SUMMER GOODS” available “at their Shop, the Sign of the Golden Eagle, near the Court-House” in Providence incorporated graphic design elements intended to attract the attention of newspaper readers and prospective customers. The copious use of all capitals and large fonts distinguished their advertisement from many others that appeared in the Providence Gazette in the spring and summer of 1768. As a result of their decisions concerning the visual aspects of their advertisement, the Russells’ notice included far less text than many others of a similar length. They traded the extra copy for distinctive graphic design.

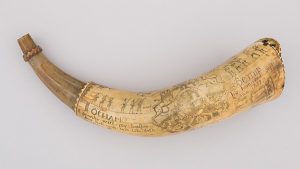

Yet not every element of their advertisement was intended for the readers of the Providence Gazette. Like many other paid notices that appeared in that publication, it concluded with a number in parentheses: in this case, “(23).” Several other advertisements in the July 2, 1768, edition also featured two-digit numbers. Shopkeepers J. Mathewson and E. Thompson and Company both had “(32)” on the final line of their advertisement. The same number appeared at the end of Joseph Whitcomb’s notice concerning a stolen horse. Isaac Field, executor to the estate of Joseph Field, inserted a notice with “(33)” on the same line as his name. Nicholas Clark’s advertisement seeking “an Apprentice to the Block-making Business” included “(34),” as did Moses Brown’s notice concerning a house for sale.

Each of these numbers corresponded to the issue in which the advertisement first appeared. The July 2 edition was issue “NUMB. 234.” The “(34)” in Clark’s and Brown’s advertisements indicated that they ran for the first time. Those with “(33)” were originally published a week earlier in the previous issue, whereas those with “(32)” were making their third appearance. The Russells’ advertisement, with its “(23),” had been running for quite some time.

These numbers aided printers and compositors in determining when to remove advertisements, especially if the advertisers had contracted for a certain number of insertions. While intended primarily for the use of those in the printing office, astute readers may have also consulted them to determine which advertisements were new and which were not. Those who perused the Providence Gazette every week would certainly have recognized advertisements they had seen multiple times, but others who did not peruse the newspaper as frequently did not have that advantage. Those numbers – likely the only portion of the copy not composed by the advertisers – were tools intended to aid those who operated the press, but they also helped readers to distinguish among notices that were new, relatively new, and not new at all.