What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

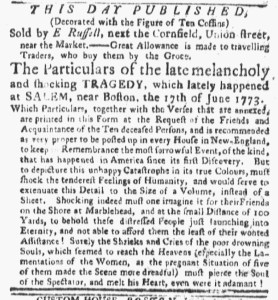

“The Particulars of the late melancholy and shocking TRAGEDY.”

Ripped from the headlines! Just a few weeks after the “melancholy and shocking TRAGEDY, which lately happened at SALEM, near Boston, the 17th of June 1773,” Ezekiel Russell advertised a broadside commemorating the deaths of ten drowning victims, three men and seven women. Compounding the tragedy, five of the women were pregnant, “two or three of them far advanced.”[1] Several boats had departed from Salem’s harbor “on Parties of Pleasure,” including one boat that took its passengers to Baker’s Island, “where they went ashore, staid and dined.” When the passengers boarded again, the boat sailed to another part of the island “for the Purpose of Fishing” and later anchored between Baker’s Island and Misery Island, “where they drank Tea.”

When the weather began to look threatening, they determined to try for Marblehead Harbour.” As the wind intensified, the men recommended to William Ward, “the Commander of the Boat,” that he lower the sails, but Ward insisted that “the Boat would stand it.” The passengers, “trusting his Judgment, thought proper to submit.” The women huddled in the cabin, out of the wind and out of the way of the men attempting to get the boat to shore. When a “sudden, smart Gust of Wind canted the Boat over on one Side,” one of the men, John Becket, had time to open the cabin door and warn the women that “they were all going to the Bottom.” The Boat “instantly sunk.” Becket and a “Lad about 15 Years old” were the only survivors. Becket reported that heard the women shrieking in their last moments. Observers on shore in Marblehead, about a mile distant, saw what happened and, “by their timely and vigorous Efforts,” launched a small schooner to retrieve Becket and the youth from the water, but it was too late to aid Ward and the women.

Russell presented an even more dramatic scene when he marketed the broadside, suggesting that the boat had been closer to shore than the newspaper accounts indicated. “Shocking indeed must one imagine it for their Friends on the Shore at Marblehead, and at the small Distance of 100 Yards,” he proclaimed, “to behold these distressed People just launching into Eternity, and not able to afford them the least of their wonted Assistance!” Ramping up his efforts to play on the emotions of prospective customers, Russell became even more melodramatic: “Surely the Shrieks and Cries of the poor drowning Souls, which seemed to reach the Heavens (especially the Lamentations of the Women, as the pregnant Situation of five of them made the Scene more dreadful) must pierce the Soul of the Spectator, and melt his Heart, even were it adamant!” It was not Russell who was ghoulish in marketing this broadside, but rather readers who could learn of this “melancholy and shocking TRAGEDY” without it affecting them. They could demonstrate that the events had indeed moved them by purchasing and displaying the broadside “Decorated with the Figure of Ten Coffins.”

The following day, colonizers from Salem and Marblehead located and raised the sunken boat. They recovered the bodies of six of women, but did not find the bodies of Mrs. Diggadon and the three men. They returned the bodies of the women to “the same Wharf from which so much Cheerfulness and Gaiety they departed the Day before.” At the funerals, the “Solemnity of the several Processions drew together a vast Number of People” of “all Ranks” to mourn the victims of such a tragedy.

That account of the tragedy first appeared in the June 22 edition of the Essex Gazette, published in Salem. Within the next ten days, the Boston Evening-Post reprinted the news on June 28 and the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter did so on July 1. Even if colonizers in Salem, Boston, and other towns did not read about the tragedy, they almost certainly heard about it given the way that local news, especially something as “melancholy and shocking” as these drownings, usually spread by word-of-mouth much more quickly than printers could set type.

Russell provided an opportunity for consumers to acquire a keepsake of the tragedy. He anticipated that they would be eager to do so, offering “Great Allowance … to travelling Traders, who buy [the broadside] by the Groce [or Gross].” In other words, peddlers who would disseminate the broadside throughout the countryside received a significant discount for purchasing by volume. Russell claimed that he did not consider it macabre to advertise and sell the broadside, asserting that it was “printed in this Form at the Request of the Friends and Acquaintance of the Ten deceased Persons.” To incite sales, whether at his shop or from itinerant peddlers, he suggested that it was “very proper to be posted up in every House in New-England, to keep in Remembrance the most sorrowful Event, of the kind, that has happened in America since its first Discovery.” Even as Russell focused on the emotional response to such a harrowing story, he participated in the commodification of recent events, just as printers, booksellers, and others did following the Boston Massacre and the death of George Whitefield.

The Library of Congress makes an image of the broadside available to the public.

**********

[1] This narrative draws from the account in the Essex Gazette. That account also appeared in the Boston Evening-Post and the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter and on the broadside.