What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Just Published, The PARTICULARS of the late Melancholy and Shocking TRAGEDY, which happened at Salem.”

The account of the “most distressing and melancholy Affair” of the drowning of three men and seven women, five of them reportedly pregnant, when their boat sank near Salem during a sudden storm on June 17, 1773, first appeared in the Essex Gazette on June 22 and then in the Boston Evening-Post on June 28 and the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter on July 1. News also spread beyond the colony where the tragedy occurred. On June 25, Daniel Fowle reprinted the account from the Essex Gazette in the New-Hampshire Gazette, though some readers likely already heard some of the details via word of mouth.

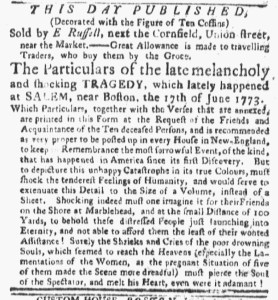

As was the case in Boston, commemoration and commodification of the drownings, entwined so tightly as to render them inseparable, soon appeared in the public prints. Ezekiel Russell first advertised a broadside “Decorated with the Figures of Ten Coffins” that related “The Particulars of the late melancholy and shocking TRAGEDY, which lately happened at SALEM” in the July 12 edition of the Boston Evening-Post. Just three days later, Russell inserted the same advertisement in the Massachusetts Spy, adding a brief note about a second broadside, “An ELEGY on the affecting Tragedy at Salem.” Fowle apparently acquired copies of the first broadside, which Russell sold “by the Groce,” to sell at his printing office. A brief advertisement in the July 30 edition of the New-Hampshire Gazette announced, “Just Published, The PARTICULARS of the late Melancholy and Shocking TRAGEDY, which happened at Salem, near Boston, on Thursday, the 17th Day of June, 1773.”

Fowle did not include any of those “PARTICULARS” in the advertisement, nor did he publish any of the extensive memorial that previously appeared in the advertisements in the other newspapers. Between the account in the New-Hampshire Gazette and conversations about the drownings, he may have thought that the broadside did not need additional explanation. He also did not have the same financial stake in marketing the broadside that Russell did, likely accepting only as many as he anticipated he could sell. Russell played on the proximity of the tragedy to Boston in marketing the broadside to readers of newspaper published in that city, though he did proclaim that it “is recommended as very proper to be posted up in every House in New-England, to keep in Remembrance the most sorrowful Event.” Fowle, on the other hand, did not assert such urgency to readers of his newspaper. He presented the broadside for prospective customers who might be interested, but did not make the same hard sell in Portsmouth as Russell did in Boston.