What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

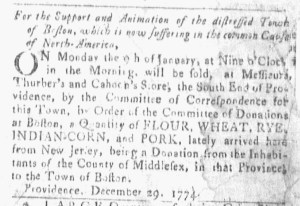

“For the Support … of the distressed Town of Boston … suffering in the common Cause of North-America.”

As 1774 ended, readers of the Providence Gazette contemplated how they could aid the town of Boston where the harbor had been closed to commerce for seven months. The Boston Port Act went into effect on June 1, retribution for the Boston Tea Party. In turn, that inspired a variety of responses, including the meetings of the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia in September and October and the formation of relief efforts for Boston. Local committees throughout the colonies started subscriptions for collecting food to send to the town, as Bob Ruppert documents in “The Winter of 1774-1775 in Boston.”

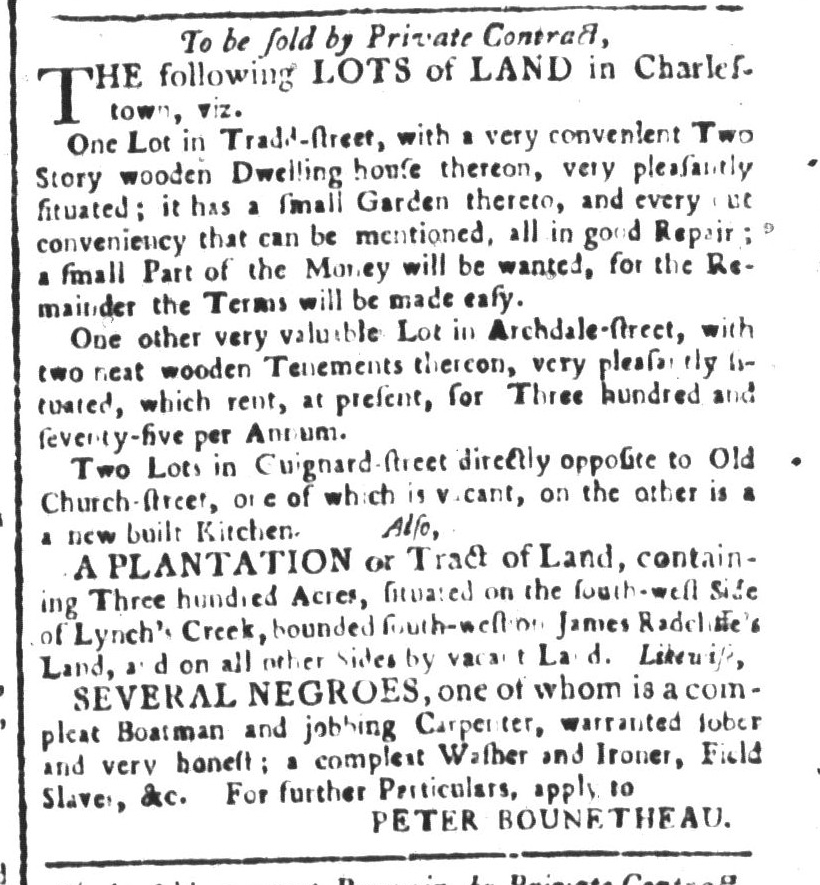

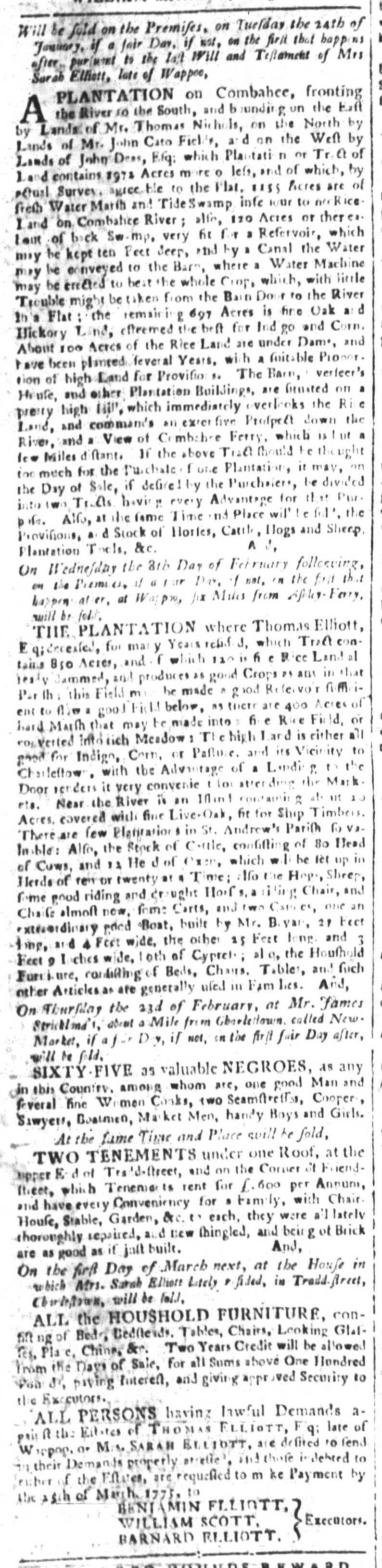

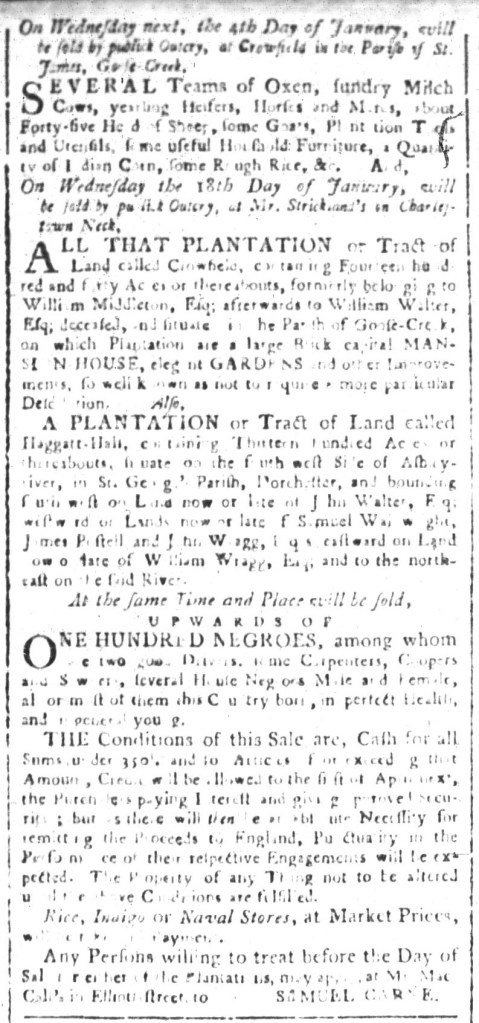

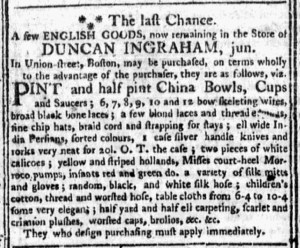

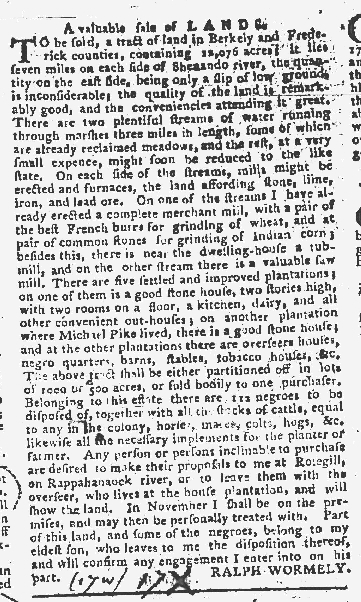

An advertisement in the December 31, 1774, edition of the Providence Gazette announced an upcoming sale of a “Quantity of FLOUR, WHEAT, RYE, INDIAN-CORN, and PORK” that would be held “For the Support and Animation of the distressed town of Boston, which is now suffering in the common Cause of North-America.” Although Parliament aimed the Boston Port Act, the Massachusetts Government Act, and the other Coercive Acts at agitators in Massachusetts, that legislation prompted a unified response, a sense of a “common Cause” as other colonies realized that Parliament could just as easily target them. The shipment of grains and pork that arrived in Providence came from New Jersey, “a Donation … to the Town of Boston.” According to the advertisement, the Committee of Correspondence in Boston instructed the Committee of Correspondence in Providence to sell the grains and pork to raise funds rather than attempt to transport them to Boston.

John Carter, the printer of the Providence Gazette, gave that advertisement a privileged place both times that it ran in his newspaper. The first time that it appeared, he inserted it immediately after local news and before other advertisements. Readers likely experienced it as a continuation of news related to the imperial crisis, including updates about other “Donations … to the Town of Boston.” When the advertisement ran a week later, two days before the sale, it was the first item in the first column on the first page, making it nearly impossible for readers to miss. Through the choices he made about the layout of his newspaper, the printer made his own contribution in support of the “common Cause of North-America.”