What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“˙ɥsɐƆ ɹoɟ dɐǝɥƆ ǝɯǝɹʇxƎ”

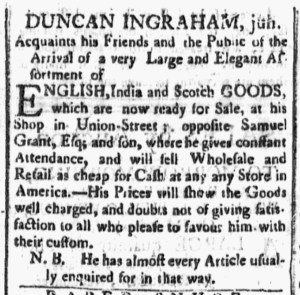

Although likely resulting from an error in the printing office, Duncan Ingraham’s advertisement in the September 16, 1773, edition of the Massachusetts Spy almost certainly caught the attention of readers. Except for a heading, “ADVERTISEMENT,” the entire notice appeared upside down at the top of the third column on the second page. The placement of the advertisement, not just its orientation, was unusual. In that issue, Isaiah Thomas, the printer, or a compositor who worked for the Massachusetts Spy reserved advertising for the final two pages, making Ingraham’s advertisement the only paid notice on the second page. It appeared after news dated, “TUESDAY, September 13. BOSTON,” and above “EUROPEAN INTELLIGENCE” dated, “WEDNESDAY, September 14. BOSTON,” the date and location based on when ship captains delivered the news to the printing office, not when and where the events occurred. Even without flipping the text, Ingraham’s advertisement was a juxtaposition from the rest of the contents on the page, meriting its own header. No separate headers for “ADVERTISEMENTS” appeared on the third or fourth pages. Had Thomas or the compositor originally intended for something else to appear in the space ultimately occupied by the upside-down advertisement?

When Ingraham’s advertisement next ran in the Massachusetts Spy, two weeks later on September 30, the compositor corrected the error. It appeared right-side up, interspersed among other paid notices on the final page. Working quickly to print the newspaper on a manually-operated press, those working in the printing office may not have caught the error after a compositor set the type for Ingraham’s advertisement and the entire block of text got rotated when added to the other contents of the second page. How did readers react? Did this work to Ingraham’s benefit? When readers encountered the upside-down advertisement, did they turn their newspaper over so they could peruse it? Upon realizing it was an advertisement rather than news, how many opted to look more closely? How many decided to ignore it in favor of continuing with updates from England, Russia, Egypt, and other faraway places? Did the unusual format at least make the advertisement’s headline, “Extreme Cheap for Cash,” more memorable for readers, even those not attentive to the remainder of the advertisement? Ingraham advertised frequently enough that regular readers would have already been familiar with the merchant. For marketing purposes, it may have been sufficient for some to see his name, “Extreme Cheap for Cash,” and a list of goods without reading through the entire inventory.

Printers, compositors, and advertisers sometimes experimented with typography in order to call more attention to certain newspaper notices. While that does not appear to have been the intention in this instance, Ingraham’s upside-down advertisement still raises questions about how readers experienced advertisements with unusual formats or placed in unusual spots within newspapers. Ingraham’s advertisement, flipped over and surrounded by news, may have garnered more notice than had it run alongside advertisements from his competitors that ran elsewhere in the Massachusetts Spy.