What was (not) advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

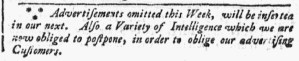

“Advertisements omitted this Week, will be inserted in our next.”

Nearly three dozen advertisements appeared in the October 7, 1771, edition of the Pennsylvania Chronicle, but William Goddard, the printer, did not have enough space to publish all of the notices submitted to his printing office on Arch Street in Philadelphia. Neither did he have room for all of the news. The final column of the third page concluded with a brief note advising that “Advertisements omitted this Week, will be inserted in our next. Also a Variety of Intelligence which we are now obliged to postpone, in order to oblige our advertising Customers.”

Colonial newspapers generated revenue along two trajectories: subscriptions and advertising. Subscribers purchased access to the “freshest advices, foreign and domestic,” as the mastheads for many newspapers described the news. Advertisers, in turn, purchased access to readers. They sought to place their notices before the eyes of as many readers as possible. Printers sometimes commented on how many subscribers received their newspapers as a means of encouraging prospective advertisers to place notices. In making decisions about what to publish, printers had to balance news and advertising in order to satisfy both subscribers and advertisers. Displeasing one constituency or the other had the potential to negatively affect revenues.

Printers regularly informed readers that they postponed advertisements, a means of assuring advertisers that their notices would indeed soon appear. Most printers, however, did not often explicitly comment on their endeavors to serve their advertisers, making Goddard’s note about “oblig[ing] our advertising Customers” all the more remarkable. He revealed to readers, subscribers and advertisers alike, that publishing advertisements sometimes took priority over “a Variety of Intelligence” that he might otherwise have published. While he framed this as a service to customers who placed notices, the revenues those advertisements represented could not have been far from his mind. Goddard was willing to delay some advertisements until the next edition, but not too many of them as he aimed to please both subscribers and advertisers.