What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He has Advice of a compleat Assortment … expected here from London every Day.”

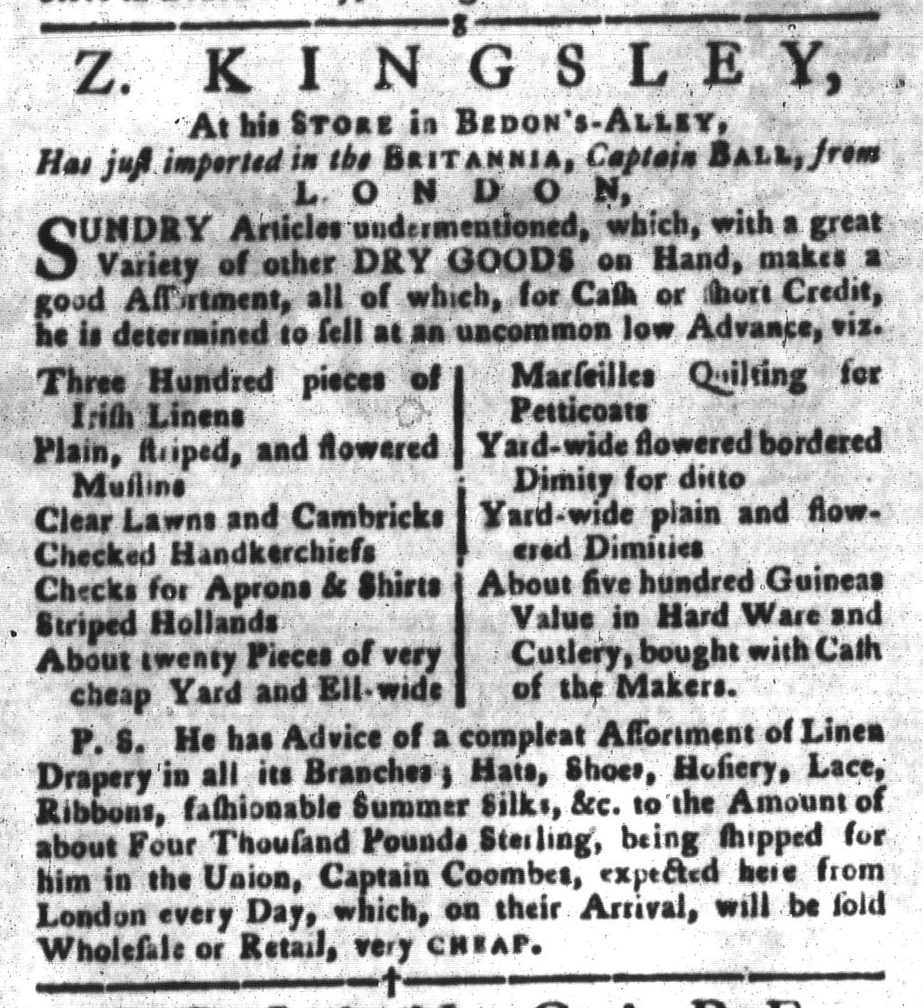

Zephaniah Kingsley trumpeted the magnitude of the inventory “At his STORE in BEDON’S-ALLEY” in an advertisement in the March 29, 1774, edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal. He promoted the “SUNDRY Articles undermentioned” in a list of items “just imported … from LONDON” as well as a “great Variety of other DRY GOODS on Hand” from previous shipments. All together, they constituted a “good Assortment” that offered a vast array of choices to consumers in Charleston. He even took the unusual step of the total worth of some of his merchandise, declaring that he stocked “About five hundred Guineas Value in Hard Ware and Cutlery.” That certainly signaled that he had indeed acquired a “good Assortment” of those items to satisfy the desires of just about any prospective customer.

The merchant opted for a postscript (rather than the more common nota bene) to alert readers that he “has Advice of a compleat Assortment of Linen Drapery in all its Branches; Hats, Shoes, Hosiery, Lace, Ribbons, fashionable Summer Silks,” and other goods “being shipped for him in the Union, … expected here from London every Day.” As if his current inventory was not enough, Kingsley encouraged a sense of anticipation for new items that matched the most current fashions in London, the most cosmopolitan city in the empire. In so doing, he once again deployed a marketing strategy that he used a couple of months earlier. In early February, he proclaimed that he “intends having ready to open as soon as possible in the spring, an elegant assortment of Linen Drapery … with a quantity of the most fashionable summer Silks.” The new advertisement served as an update for customers whose attention Kingsley caught with that preview. In his effort to sell all his merchandise, including goods already “on Hand,” the merchant emphasized new items and even those that had not yet arrived but that he would make available to consumer imminently. Curiosity about those goods, he likely reasoned, could help in moving older inventory out of his store once he got customers through the doors.