What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He carries on the Bookbinding and Stationary business in an extensive manner.”

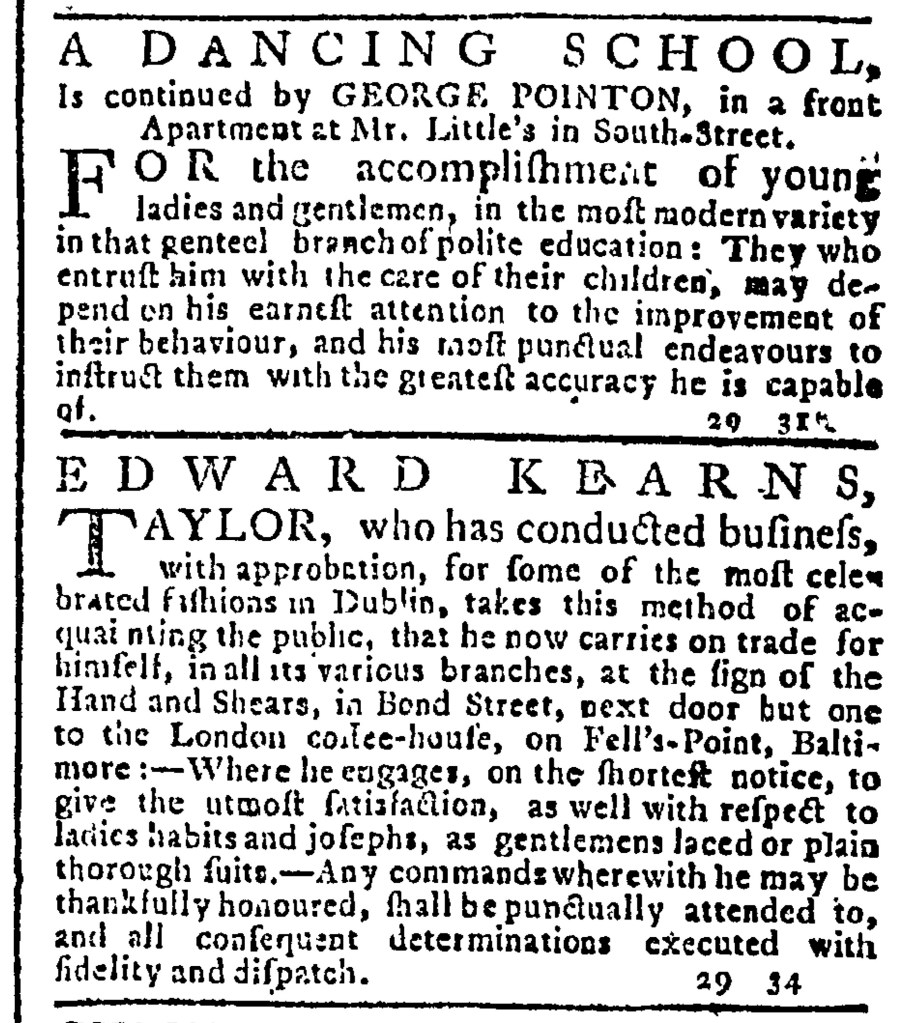

Among the many advertisements that ran in the August 29, 1774, edition of Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet, one from William O’Brien offered several goods and services. He first offered several varieties of alcohol and popular groceries, including “Jamaica spirit, West-India and continent rum, all kinds of wines, tea and sugar of different kinds, coffee, cordials and patent medicines.” In addition to that inventory, he also stocked “a large collection of the best books, both antient and modern.” Yet O’Brien also identified himself as a bookbinder and stationer, promoting in particular custom-made account books, ruled or unruled, to any size as bespoke.” He offered those items to both merchants and retailers who might buy in volume “to sell again.”

Although O’Brien advertised in Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet, published in Philadelphia, he lived and worked in Baltimore. He likely did not expect that his notice would generate much business among readers in Philadelphia; instead, he sought customers in his own town and the surrounding area, realizing that for many years the Pennsylvania Gazette, the Pennsylvania Journal, Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet, and other newspapers printed in Philadelphia served as local newspapers for towns in Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, and Maryland. O’Brien could have chosen to advertise in the Maryland Journal, Baltimore’s first newspaper, in addition to or instead of one of the newspapers in Philadelphia, though he may have had doubts about the efficacy of doing so. Commencing publication on August 20, 1773, the Maryland Journal had just marked its first year, yet its appearance had been sporadic during that time rather than sticking to a weekly schedule. O’Brien turned to a more reliable newspaper, likely familiar with its circulation in Maryland and, as a result, having greater confidence in the money he invested in advertising in Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet. William Goddard, the printer of the Maryland Journal, still had work to do to win over prospective advertisers in Baltimore.