What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“No ADVERTISEMENTS … can be inserted for the future without the Cash accompanies them.”

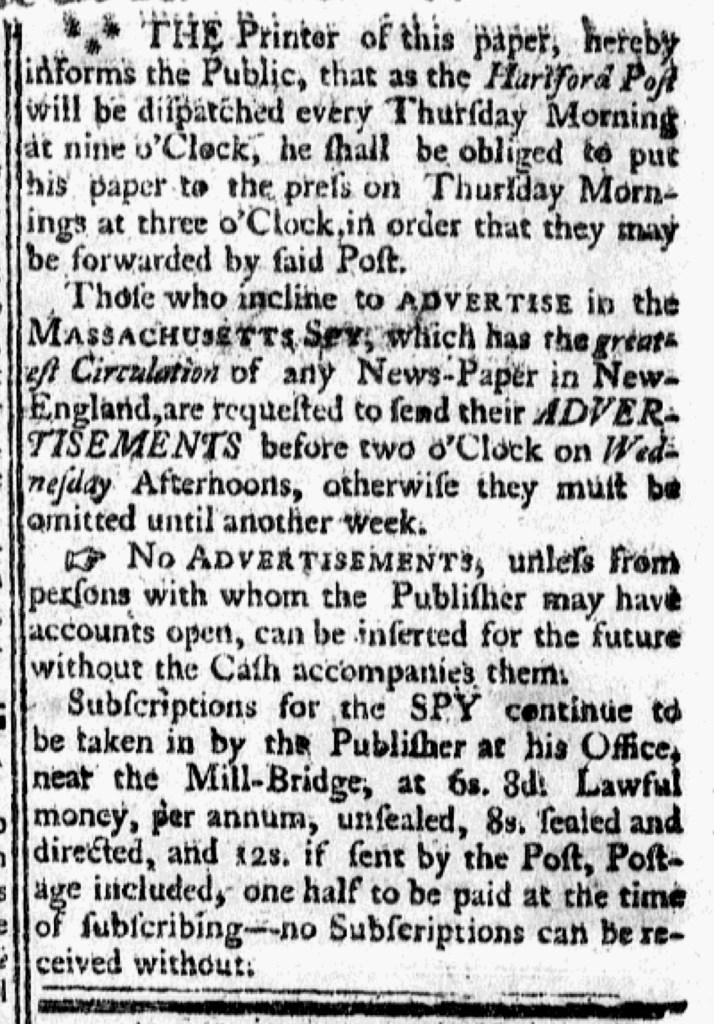

In a notice in the January 19, 1775, edition of the Massachusetts Spy, Isaiah Thomas, the printer, provided several important details about the practices he enacted for publishing his newspaper. He opened by noting that “the Hartford Post will be dispatched every Thursday Morning at nine o’Clock.” In order that that the Massachusetts Spy “may be forwarded by said Post,” Thomas “shall be obliged to put his paper to the press on Thursday Mornings at three o’Clock.” Calling attention to such early mornings not only testified to the industriousness of the printer but also alerted the public that he could publish updates that arrived at his printing office merely hours before he distributed the new issue of his weekly newspaper.

Thomas also advised “[t]hose who incline to ADVERTISE in the MASSACHUSETTS SPY … to send their ADVERTISEMENTS before two o”Clock on Wednesday Afternoons, otherwise they must be omitted until another week.” To convince them to advertise in in his newspaper, he proclaimed that it “has the greatest Circulation of any News-Paper in New-England.” That meant that advertisers were likely to experience the greatest return on their investment by placing notices in the pages of the Massachusetts Spy. Although compositors worked quickly, they did need some time to set type for individual advertisements and lay out all the news, editorials, advertisements, and other content for each issue. While Thomas might welcome “Articles of Intelligence” that arrived very shortly before taking his newspaper to press, he insisted that advertisements required more time to prepare for publication. Advertisers needed to plan accordingly.

In addition, Thomas declared, “No ADVERTISEMENTS, unless from persons with whom the Publisher may have accounts open, can be inserted for the future without the Cash accompanies them.” He also asserted that subscriptions for the newspaper required “one half [of the annual fee] to be paid time of subscribing” and “no Subscriptions can be received without.” Historians of the early American press often make general statements about printers extending generous credit to subscribers, expecting that some would never pay, because they understood that newspaper advertisements were a much more most significant revenue. According to such accounts, printers supposedly insisted on receiving payment for advertisements in advance of publishing them. While that may have been the case in some printing offices, several printers published notices indicating that they departed from such practices. That Thomas put in place such a policy “for the future” suggests that it may have been a new policy or one that he had not previously enforced. Similarly, Thomas joined other printers who extended credit yet also demanded that subscribers submit half of the annual fee in advance, updating the terms that he published in the colophon that appeared in each issue of the Massachusetts Spy.