What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“DR. BLOUIN … makes and sells the Antivenereal Pills, so well known … by the name of Keyser’s Pills.”

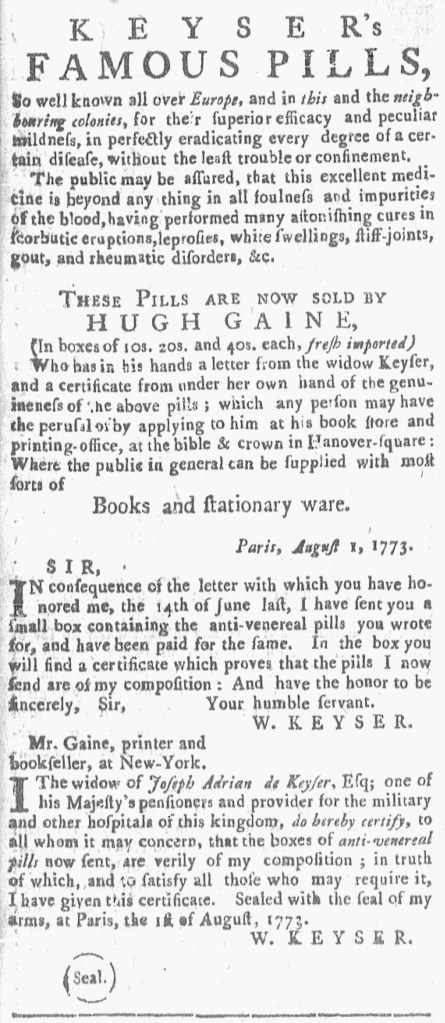

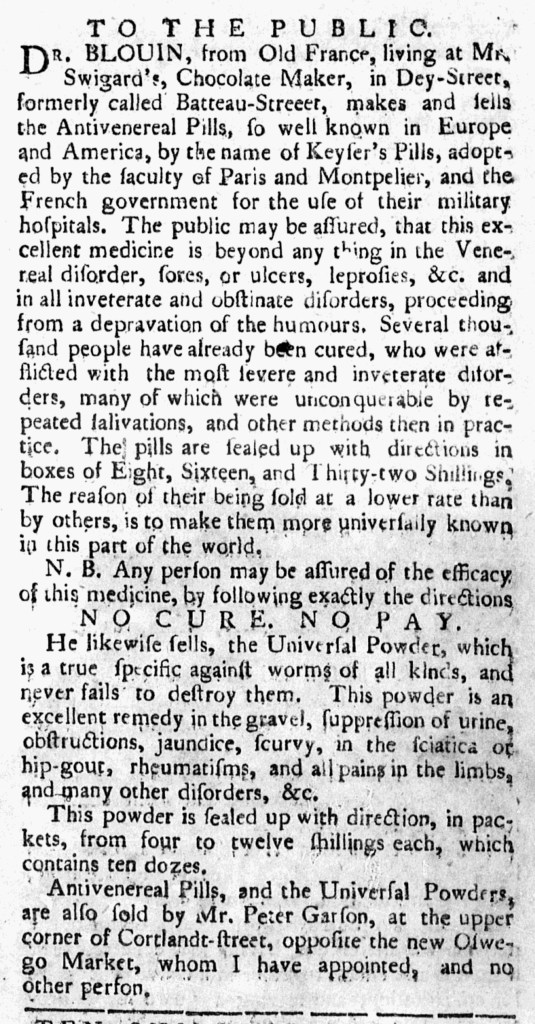

It was the eighteenth-century version of offering a generic medication at a lower price than the name brand in hopes of attracting customers. An entrepreneur who identified himself as “DR. BLOUIN, from Old France,” placed an advertisement in the November 15, 1775, edition of the Constitutional Gazette to inform readers in New York that he makes and sells the Antivenereal Pills, so well known in Europe and America, by the name of Keyser’s Pills.” Indeed, that medication was popular in the colonies, advertised frequently by apothecaries, shopkeepers, and even printers who sold patent medicines as an alternate revenue stream. At the same time that Blouin ran his advertisement, James Rivington, the printer of Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, continued running his notice that proclaimed, “EVERY ONE THEIR OWN PHYSICIAN, By THE USE OF Dr. KEYSER’s PILLS.” Rivington had been using that familiar refrain in his advertisements for years.

Blouin offered a brief history of the original medication as a means of marketing his generic version, noting that Keyser’s Pills had been “adopted by the faculty of Paris and Montpelier, and the French government for the use of their military hospitals.” Furthermore, “[s]everal thousand people have already been cured, many of which were unconquerable by … other methods” of treatment. Prospective customers, Blouin claimed, could not find a more effective remedy: “The public may be assured, that this excellent medicine is beyond any thing in the Venereal disorder, sores, or ulcers, leprosies, &c. and in all inveterate and obstinate disorders, proceeding from a depravation of the humours.” He was so certain that he offered a guarantee: “NO CURE. NO PAY.”

Readers interested in purchasing the pills that Blouin made in New York rather than imported ones would receive printed directions and could choose among boxes costing eight, sixteen, and thirty-two shillings. The efficacy of the cure, he cautioned, depended on “following exactly the directions.” Rivington sold Keyser’s Pills for ten, twenty, and forty shillings. Blouin explained that he gave a discount “to make [his generic pills] more universally known in this part of the world.” For those who wavered in choosing his pills over the name brand version, he hoped that the lower price would help convince them. Blouin also noted that an associate, Peter Garson, “at the upper corner of Cortlandt-street, opposite the new Oswego Market,” sold the pills, but “no other person.” Many advertisements for Keyser’s Pills warned prospective customers about counterfeits. Blouin freely admitted that he “makes and sells” his own version … and advised readers to avoid any attributed to him but not sold by him or his appointed agent.