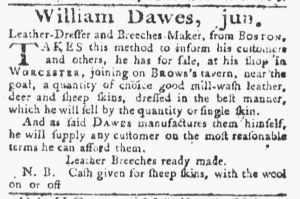

What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Leather-Dresser and Breeches-Maker, from BOSTON.”

William Dawes, Jr., a “Leather-Dresser and Breeches-Maker, from BOSTON,” placed an advertisement in the January 26, 1776, edition of Thomas’s Massachusetts Spy. Just as Isaiah Thomas had moved his printing press from tumultuous Boston to the relative security of Worcester just as the Revolutionary War began, Dawes relocated to the inland town. According to his advertisement, he now ran a shop “in WORCESTER,” adjoining a tavern and near the jail. Since he was a newcomer, he could not expect that prospective customers knew his location, so he identified familiar landmarks to help them find him. He had on hand “a quantity of choice good mill-washed leather, [and] deer and sheep skins, dressed in the best manner,” selling them either individually or “by the quantity.” Dawes processed or “manufacture[d]” the leather himself, allowing him to “supply any customer on the most reasonable terms he can afford them.” To that end, he sought “sheep skins, with the wool on or off,” and offered cash to his suppliers.

Under other circumstances, identifying himself as an artisan “from BOSTON” would have told prospective customers something about his origins and suggested that he possessed the skills and knowledge of changing styles that allowed him to run a business in one of the largest urban ports in the colonies. While that was still the case in this advertisement, noting that he was “from BOSTON” likely resonated in another way. The residents of that town had endured a lot during the imperial crisis, especially after the Boston Port Act closed the harbor to commerce on June 1, 1774, in retaliation for the destruction of tea the previous December. The situation became even more precarious once the fighting began at the battles at Lexington and Concord in April 1775. A siege of Boston ensued. The Second Continental Congress appointed George Washington as commander of the Continental Army and dispatched him to lead the American forces that surrounded Boston. Early in the siege, the Sons of Liberty and other leaders negotiated with General Thomas Gage for an exchange, allowing Loyalists to enter Boston and Patriots and others to depart. Dawes may have been among those refugees in search of better fortunes and greater safety in other towns in New England. By introducing himself as a “Leather-Dresser and Breeches-Maker, from BOSTON,” he may have hoped to play on the sympathies of prospective customers, giving them one more reason to support his shop in Worcester.