What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He can afford selling them cheaper than any ever imported in this province.”

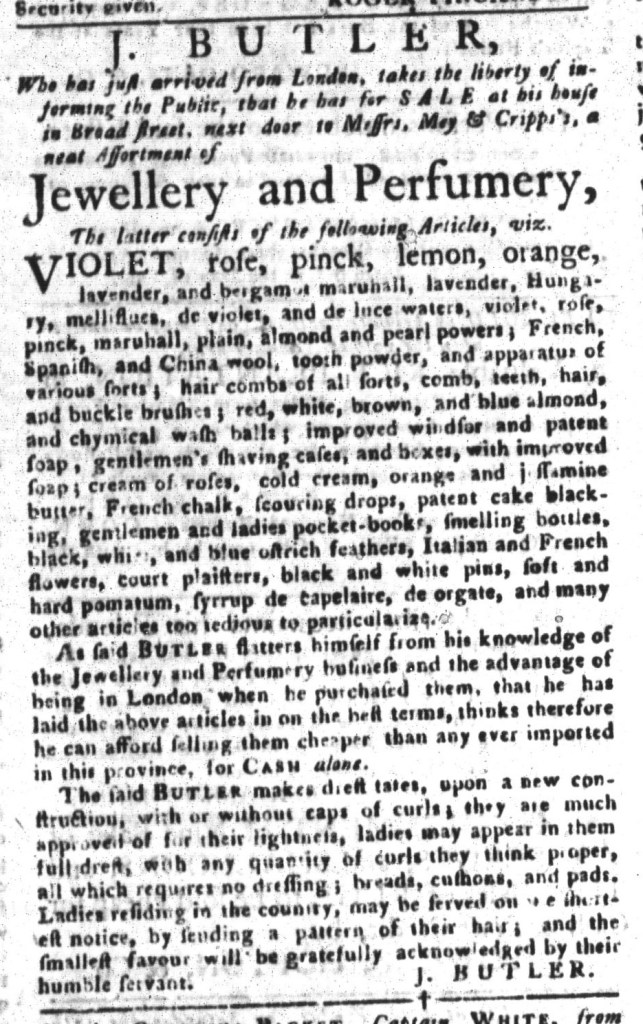

J. Butler’s advertisement in the November 8, 1774, edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal proclaimed that he sold “Jewellery and Perfumery” at a shop he operated at his house on Broad Street in Charleston. Among the perfumery, he provided “VIOLET, rose, pinck, lemon, orange, lavender, and bergamot.” In addition, he listed a variety of personal hygiene products and cosmetics that he stocked, including “tooth powder, … hair combs of all sorts, … gentlemen’s shaving cases and boxes, with improved soap, … cold cream, [and] soft and hard pomatum.” If that was not enough to attract consumers looking to pamper themselves, Butler also proclaimed that he carried “many other articles too tedious to particularize.” Readers could cure their curiosity with a visit to Butler’s shop.

As further encouragement, he emphasized that he had “just arrived from London.” Rather than accept merchandise shipped to him without first examining it himself, Butler had carefully examined and thoughtfully selected the wares he now advertised. He considered that an “advantage,” especially in combination with “his knowledge of the Jewellery and Perfumery business,” that allowed him to acquire his inventory “on the best terms.” In turn, he passed along the savings to his customers, asserting that “therefore he can afford selling [the above articles] cheaper than any ever imported in this province.” According to Butler, he not only offered the best prices at that moment, but the best bargains for “Jewellery and Perfumery” ever seen in South Carolina thanks to savvy negotiations with suppliers when he was in London.

Butler was not alone in suggesting that his personal oversight in obtaining his wares accrued benefits to his customers. Elsewhere in the same issue, Henry Calwell ran a short advertisement that announced he “just arrived from the Northward” and sold a “Large Quantity of Cheese, Chocolate, Potatoes, Onions,” and other groceries. He added a note that “the Chocolate he warrants to be good, as he saw it made himself.” Both Butler and Calwell sought to convince consumers that their personal connections to their merchandise should make those items more appealing.