What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

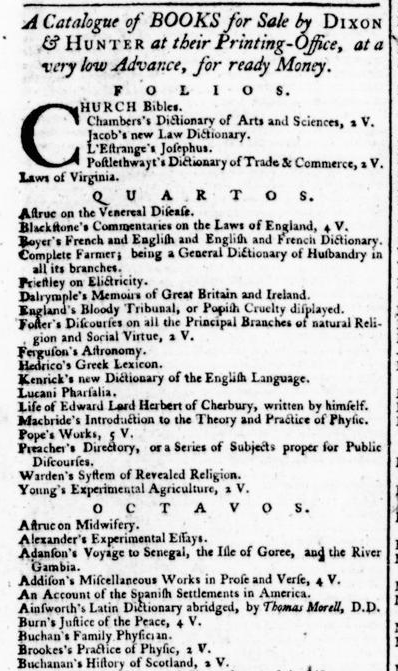

“FOLIOS … QUARTOS … OCTAVOS … DUODECIMOS.”

John Dixon and William Hunter, printers of the Virginia Gazette, published a “Catalogue of BOOKS for Sale … at their Printing-Office” in the November 25, 1775, edition. It covered most of the first page, except for the masthead and a short advertisement in which William Hewitt announced his intention to leave the colony and called on associates to settle accounts, and continued onto the second page, where it filled an entire column and overflowed into another. Overall, Dixon and Hunter’s book catalog accounted for four of the twelve columns of news and advertising in that issue. The printers could have printed a separate catalog (and very well may have done so), but disseminating the list of books they sold in the newspaper guaranteed that they reached consumers throughout the colony and beyond.

The printers deployed two principles in organizing the contents of their book catalog. First, they separated the books by size – folios, quartos, octavos, and duodecimos – and then they roughly alphabetized them. The catalog featured only half a dozen folios, including “CHURCH Bibles,” “Chambers’s Dictionary of Arts and Sciences” in two volumes, and the “Laws of Virginia,” along with nearly a score of quartos. Dixon and Hunter stocked many more octavos and duodecimos with more than one hundred of each for prospective customers to choose. In roughly alphabetizing the titles, they first indicated the author and then, if the book did not have an author associated with it, the title. They clustered titles together by the first letter, but they did not observe strict alphabetical order within those clusters. For example, the entries for “A” among the duodecimos appeared in this order:

Addison’s Mescellaneous Works in prose and verse, 4 V.

Adventurer, 4 V.

American Gazetteer, 3 V.

Adventures of a Jesuit, with several remarkable Characters and Scenes in real Life, 2 V.

Agreeable Ugliness, or the Triumph of the Graces.

Apocrypha.

Alleine’s, Alarm to Unconverted Sinners.

A single entry for “Y” – “Yorrick’s Sermons, 7 V.” – appeared at the end of the catalog, immediately above “INTELLIGENCE from the Northern Papers.”

Even with all the “INTELLIGENCE” from London and Philadelphia and proclamation from the royal governor of Virginia, Dixon and Hunter made room in the Virginia Gazette for their book catalog. They delivered news to their readers, but they also depended on book sales to supplement subscriptions, advertising, and job printing. Compared to many book catalogs published earlier in the century, they presented a more organized list of titles. Earlier book catalogs often separated titles by size. By roughly alphabetizing the entries, Dixon and Hunter attempted to help prospective customers find the titles that interested them.