What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“I beg the Assistance of all the Friends to our righteous Cause to circulate this Paper.”

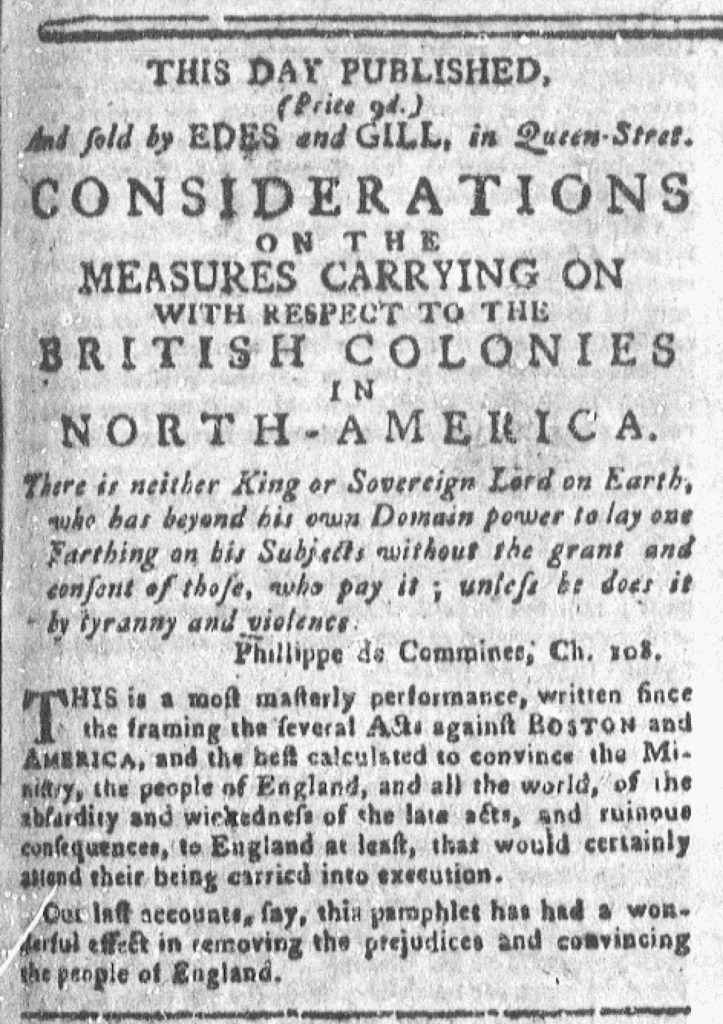

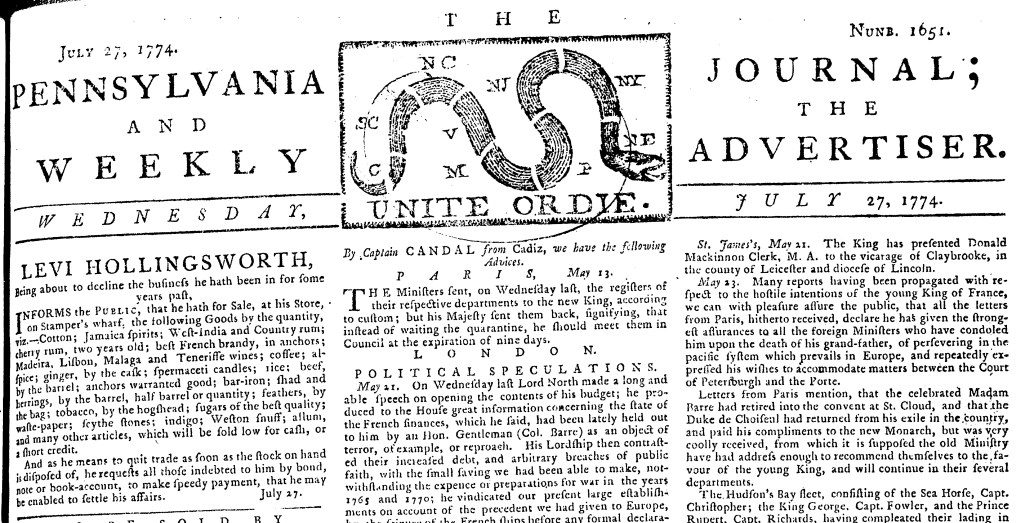

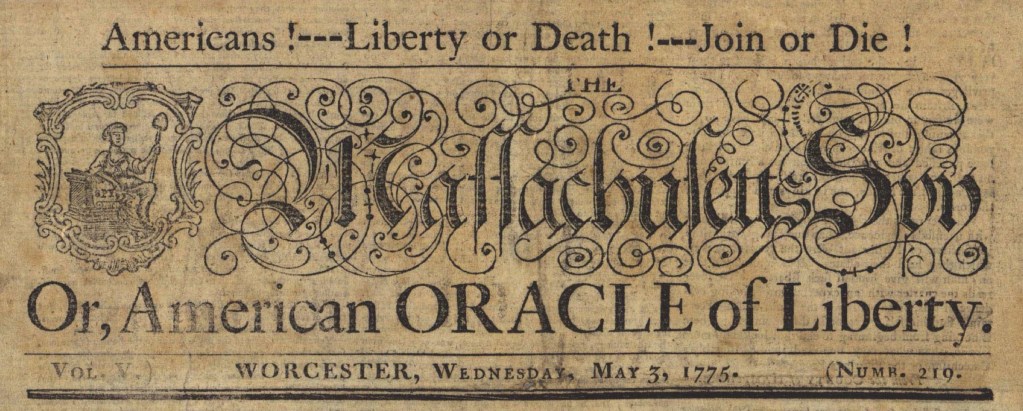

When the patriot printer Isaiah Thomas revived the Massachusetts Spy, originally published in Boston, after fleeing to Worcester to evade “friends of the British administration” who “openly threatened him with the effects of their resentment,” the first issue published in that town opened with a notice to the public.[1] He reminded readers that he had previously entered into an agreement to aid in establishing a press in Worcester, installing a junior partner to manage a printing office there while he oversaw the enterprise from Boston. He had issued proposals for the newspaper, intending to name it the “WORCESTER GAZETTE, or AMERICAN ORACLE of LIBERTY.” However, when Thomas determined that it became “highly necessary that I should remove my Printing Materials from Boston to this Place,” he decided to “continue the Publication of the well-known MASSACHUSETTS SPY, or THOMAS’S BOSTON JOURNAL.” He continued the numbering but gave it a new title, combining elements of the existing one and the proposed one: Massachusetts Spy Or, American Oracle of Liberty. In addition, the masthead proclaimed, “Americans! — Liberty or Death! — Join or Die!”

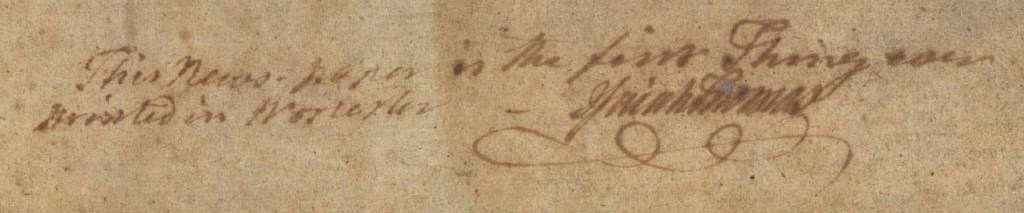

In his notice, Thomas reported that first he sent his “Printing Utensils” to Worcester and then “escaped myself from Boston on the memorable 19th of April, 1775, which will be remembered in the future as the Anniversary of the BATTLE of LEXINGTON!” Elsewhere that first issue published in Worcester, Thomas provided a chronicle of the battle “collected from those whose veracity is unquestioned.” That narrative likely incorporated elements drawn from the printer’s own firsthand account. Several years later, he recorded that at daybreak on April 19 he “crossed from Boston over to Charlestown in a boat with Dr. Joseph Warren, went to Lexington, and joined the provincial militia in opposing the king’s troops.”[2] The following day, went to Worcester to open the printing office and revive his newspaper. He was proud of that work and the service he provided, making a note and signing his name in the margin at the bottom of the first page of the first issue published there: “This News-paper is the first Thing ever printed in Worcester – Isaiah Thomas.”

Having installed himself in that town, he made clear his purpose in publishing the Massachusetts Spy as such momentous events occurred. He pledged to give “the utmost of my poor Endeavours … to maintain those Rights and Priviledges for which we and our Fathers have bled!” To that end, he would “procure the most interesting and authentic Intelligence” to keep his readers in central Massachusetts and beyond informed of the latest news. In addition, he called on “all the Friends to our righteous Cause” to aid in circulating the Massachusetts Spy. Many had already enlisted in that endeavor, serving as local agents who collected the names of subscribers and forwarded them to the printing office. In revised proposals that ran immediately below Thomas’s notice, he listed associates who accepted subscriptions in nearly three dozen towns in Worcester County and indicated that “many other Gentlemen in several parts of the province” did as well.

Of the five newspapers published in Boston at the beginning of April 1775, the Massachusetts Spy was the first to suspend publication, the decision resulting from Thomas leaving town rather than the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington and Concord. It was also the first to resume circulating weekly issues on a regular schedule, a result of the printer’s foresight in relocating to Worcester. Some of the other newspapers folded completely, but the Massachusetts Spy continued throughout the war and well beyond.

Click here to view the entire May 3, 1775, edition of the Massachusetts Spy, including Thomas’s note on the first page and the account of the Battle of Lexington on the third page. That copy is in the collections of the American Antiquarian Society, founded by Thomas in 1812.

**********

[1] Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America: With a Biography of Printers and an Account of Newspapers (1810; New York: Weathervane Books, 1970), 168

[2] Thomas, History of Printing, 168-9.