What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

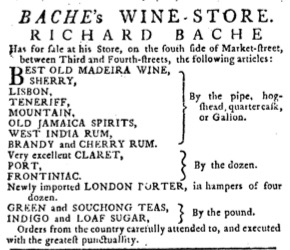

“GREEN and SOUCHONG TEAS.”

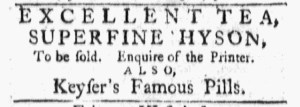

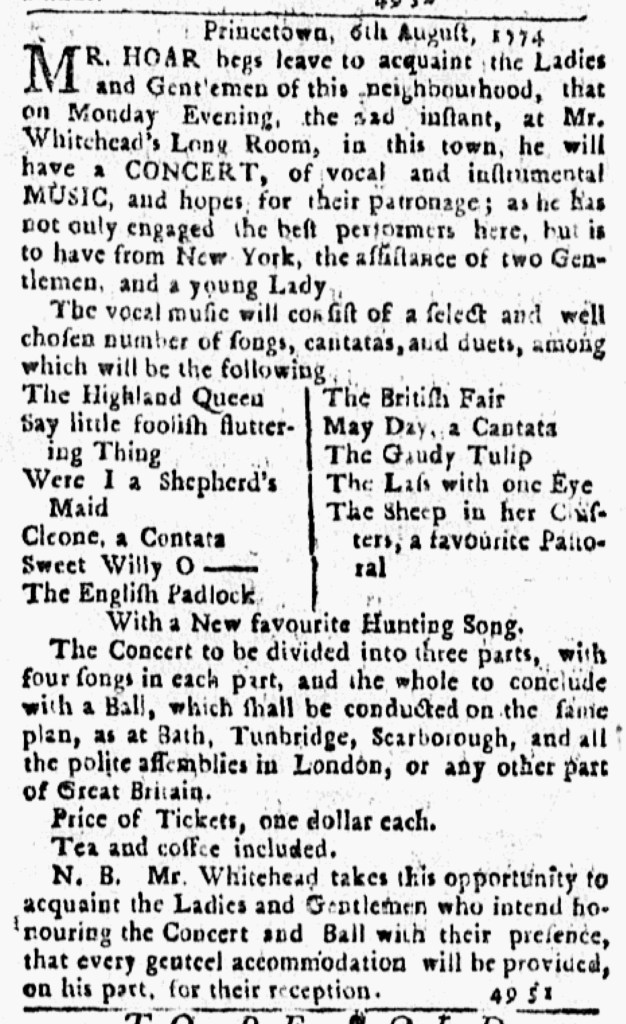

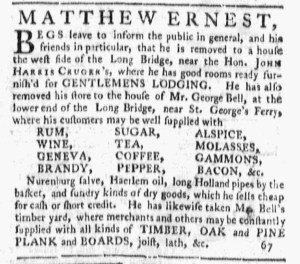

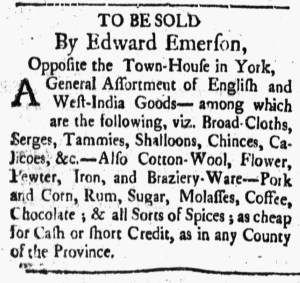

A year after the Boston Tea Party, advertisements for tea continued to appear in newspapers throughout the colonies. They even continued to run after the Continental Association, a nonimportation agreement adopted by the First Continental Congress, went into effect on December 1, 1774. The December 14, 1774, edition of the Pennsylvania Journal, for instance, carried two advertisements, side by side at the top of the final page, that included tea among the commodities offered for sale. “BACHE’s WINE-STORE” stocked more than just wine and spirits. Richard Bache also promoted “GREEN and SOUCHONG TEAS … By the pound.” Similarly, “JOHN MITCHELL’s Wine, Spirit, Rum and Sugar STORES” provided consumers with “Bohea Tea, warranted good, by the chest, half chest or dozen” and “Best Green and Hyson Tea, by the dozen or pound.” These advertisements apparently did not meet with the sort of ire that resulted in Bache or Mitchell quickly discontinuing them. Instead, James R. Fichter documents in Tea: Consumption, Politics, and Revolution, 1773-1776, that “between May 1774 and March 1775 their ads appeared most weeks.”[1]

That seems incongruous considering the editorial position of the Pennsylvania Journal and the actions of William Bradford, one of its printers. Fichter explains that Bradford “hosted in his home the meeting which decided how to oppose the East India Company’s shipment to Philadelphia in 1773. Furthermore, he published “John Dickinson’s denunciation of the 1773 tea scheme, the broadsides from ‘Committee on Tarring and Feathering,’ which threatened pilots” who brought ships carrying tea up the Delaware River, and the “JOURNAL OF THE PROCEEDINGS” of the First Continental Congress. On July 27, 1774, the Pennsylvania Journal altered its masthead to include a woodcut depicting a severed snake, each segment labeled to represent one of the colonies, and the motto, “UNITE OR DIE.” How did advertisements that offered tea for sale find their way into such a newspaper so regularly? Fichter explains that Bradford “was also a business” as well as a Patriot. Like other newspaper printers who shared his political principles, he “did not censor tea ads” but instead “ran these ads as long as they were politically permissible.” Even so late in 1774, “discourse and consumption were only partially politicized,” Fichter asserts, “and advertisements remained separate from but parallel to political debate.”[2] While that was the case for advertisements about tea, other advertisements did take positions, either implicitly or explicitly, about the politics of consumption, yet Fichter demonstrates the complexity and nuance in how printers, advertisers, and the public approached such issues. Neither the Boston Tea Party nor the Continental Association resulted in colonizers immediately giving up tea or other imported goods.

**********

[1] James R. Fichter, Tea: Consumption Politics, and Revolution, 1773-1776 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2023), 143.

[2] Fichter, Tea, 143.