Who was the subject of an advertisement in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

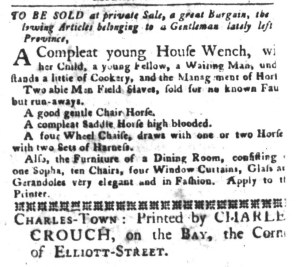

“TO BE SOLD … Two able Men Field Slaves … Apply to the Printer.”

On behalf of a customer, “a Gentleman lately left the Province,” Charles Crouch, the printer of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, advertised a variety of “Articles” available “at private Sale, a great Bargain.” Those articles included horses, a carriage with two sets of harnesses and “the Furniture of a Dining Room, consisting of one Sopha, ten Chairs, four Window Curtains, Glass and Gerandoles.” Crouch informed interested parties that they should “Apply to the Printer,” taking on the role of broker and intermediary.

In addition to the horses and housewares, the “Articles” for sale also include people treated as commodities. The list commenced with a “compleat young House [Woman], with her Child, a young Fellow, a Waiting Man, understands a little of Cookery, and the Management of Horses” and “Two able Men Field Slaves, sold for no known Fault but run-aways.” Crouch, the printer, facilitated the sale of those enslaved people, perhaps even earning a commission. He certainly generated revenue from running the advertisement in his newspaper, along with more than a dozen advertisements concerning enslaved people in the September 20, 1774, edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal. Peter Bounetheau and Jacob Valk, brokers of “LANDS, HOUSES, NEGROES, and other Property,” placed many of the others, making them good customers for the newspaper. In this instance, however, Crouch acted as a slave broker, assuming responsibilities beyond printing and disseminating the advertisement. The placement of the colophon underscored that was the case. It appeared immediately below the advertisement: “CHARLES-TOWN: Printed by CHARLES CROUCH, on the BAY, the Corner of ELLIOTT-STREET.”

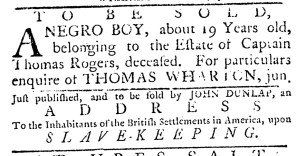

Two days ago, the Slavery Adverts 250 Project, a companion to the Adverts 250 Project, marked eight years of identifying, remediating, and republishing advertisements about enslaved people originally published in American newspapers 250 years ago that day. To date, the project includes more than 27,000 advertisements place for various purposes, such as enslaved people for sale, enslaved people wanted to purchase or hire, and descriptions of enslaved people who liberated themselves by running away from their enslavers (as two of the enslaved men in today’s advertisement had done at some point, perhaps captured and returned to slavery as a result of the surveillance encouraged by a newspaper advertisement). In many instances, advertisements offering enslaved people for sale incorporated some variation of “enquire of the printer.” From New England to Georgia, printers like Crouch provided an information infrastructure for perpetuating slavery and the slave trade and even served as agents who brokered sales of enslaved men, women, and children.