What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

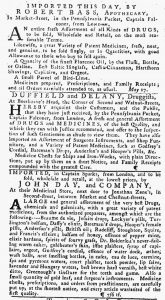

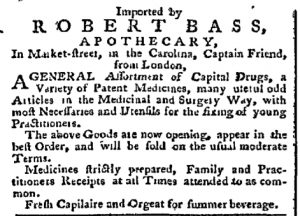

“APOTHECARY in MARKET-STREET.”

Robert Bass ran an apothecary shop in Philadelphia in the early 1770s. Along with several other apothecaries, he regularly advertised in the various newspapers published in the Quaker City. In the fall of 1773, he expanded his marketing efforts to include the Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser. That newspaper, the first in Baltimore, commenced publication near the end of August. Previously, residents of that growing port and nearby towns relied on the Maryland Gazette, printed in Annapolis, and newspapers from Philadelphia as their local newspapers. Merchants, shopkeepers, and artisans in Baltimore sometimes placed advertisements in those publications. Similarly, advertisers based in Philadelphia, including apothecaries, often mentioned that they served customers in the countryside and promptly filled orders that they received from a distance. When Bass placed advertisements in the Pennsylvania Chronicle or the Pennsylvania Gazette, for instance, he expected that prospective customers in Baltimore (and many other towns) would see them.

The founding of the Maryland Journal altered the print culture landscape in the region. The newspapers that previously served Baltimore and its environs continued to circulate there, but residents had more immediate access to a local newspaper. Hoping to retain his share of the market or perhaps even make gains via advertising in the new publication, Bass quickly decided to place notices in the Maryland Journal. His advertisement received a privileged place in the October 23 edition. It appeared as the first item in the first column on the first page, below a masthead for “NEW ADVERTISEMENTS.” The apothecary advised that he had just acquired “a very large supply of capital DRUGS and PATENT MEDICINES, to serve the fall and winter seasons.” In addition, he “properly compounded” prescriptions at his shop. Unfortunately for Bass, he was not the only advertiser who offered such services. Two columns over, Patrick Kennedy, “Surgeon and Apothecary,” hawked “a large assortment of patent medicines” and declared that he “carefully prepared” prescriptions at his shop in Baltimore. Readers who lived relatively close to Kennedy’s shop may have preferred to obtain their medicines from him as a matter of convenience, but for prospective customers in the countryside it may not have mattered whether they sent orders to Baltimore or Philadelphia. Bass even expected that some readers would visit his shop, advising that he gave “constant attendance every day except Sundays.” Although Baltimore now had its own newspaper, Bass did not consider it a separate local market. Instead, he attempted to use the new publication to maintain or even expand his share of a regional market. Whatever the outcome may have been, he considered it worth the investment of placing an advertisement in some of the first issues of the Maryland Journal.