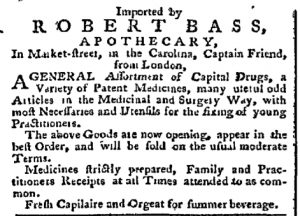

Looking back at the two projects I worked on, the Adverts 250 Project and the Slavery Adverts 250 Project, I went through a lot of digitized newspapers dating back 250 years ago. They were originally published in revolutionary America. I dealt with many different topics in those advertisements, ranging from spermaceti candles to runaway slaves.

When working on the Adverts 250 Project and when I was learning about the process of “doing” history I was amazed by all the work historians have to do for a living. But at the same time I was loving going through old newspapers and discovering all different kinds of products or services colonists put in newspapers. Then after looking at just the surface of the advertisements by themselves, I than had to do further research to fully understand the topic that I would be presenting to an audience of readers. I used scholarly sources, such as essays from Colonial Williamsburg, which were great sources for historical context and more information. This really helped me dig deeper than just the newspaper advertisement itself. That is what I felt “doing” history was really about, taking that further step to understand the advertisement I picked and deliver a summary that went beyond the advertisements to give good background information.

I thought it was pretty rewarding at the end of my week as guest curator for the Adverts 250 Project. One reason it was rewarding was because it was a lot of work at the beginning all the way to the end of the project. Having to gather the digital copies of the newspapers and learning how to uploading them to Dropbox was rewarding. Going to the American Antiquarian Society and having to get an official reader card, my first library card in a long time, was rewarding, along with working in their reading room and accessing digital copies of certain newspapers only from their website was pretty cool. Another thing about this project that I thought was rewarding was analyzing advertisements and writing summaries of everything that I learned from those advertisements and then having them posted on a public history website for the whole world to see. Overall, everything that had to do with the Adverts 250 Project was rewarding, especially after putting the long hours of work. Seeing my entries viewed by an audience outside of Assumption College was a great experience.

It also made it more rewarding because this project was more difficult than I expected. The process was tiring and time consuming. It was a lot more work than what I expected. I thought we were going to look at some newspaper advertisements and then write about them and be done. Instead it was much more than that. It involved looking at all the newspapers for my week of April 7-13. Within my week I had to look at more than twenty different newspapers and decide which advertisements I wanted to pick. After that, I had to do a lot of more research than I thought. Then I had to revise them according to suggestions by Prof. Keyes before I could have them published on the website. All of that was not what I was expecting and made it difficult for me to adjust my way of thinking and start to meet all the requirements. But at the end of it all even though it was a difficult process it was well worth it and I was glad to be a part of the Adverts 250 Project.