What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“SMALL SWORDS … of various sorts.”

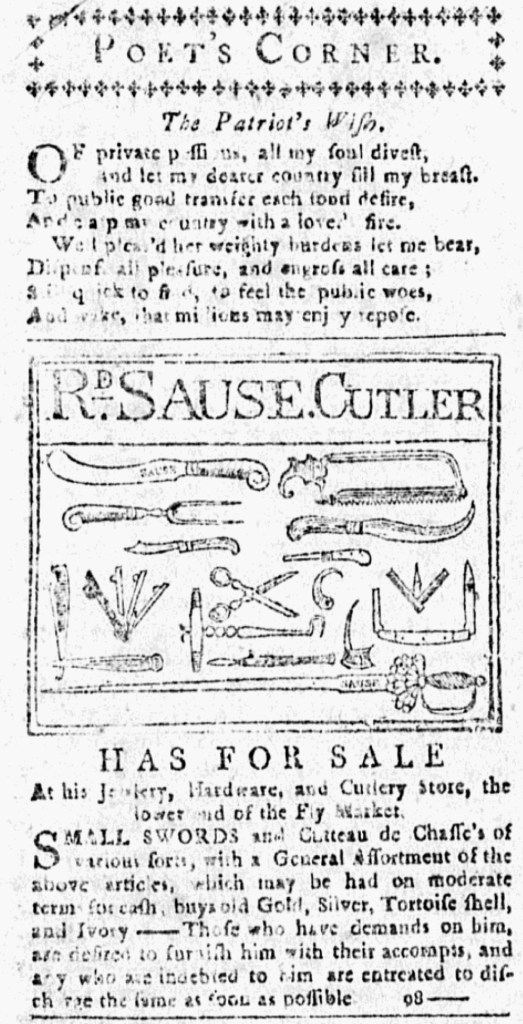

Richard Sause’s advertisement for “SMALL SWORDS” and other items available at his “Jewelery, Hardware, and Cutlery Store” became a familiar sight for readers of the New-York Journal in the summer of 1775. The woodcut depicting a shop sign with Sause’s name and an array of cutlery, including a sword, made his notice even easier to spot.

On September 14, his notice happened to appear near the top of the left column on the final page of the newspaper, immediately below a regular feature called “POET’S CORNER.” For that issue, John Holt, the printer, selected a short poem, “The Patriot’s Wish.”

OF private passions, all my soul divest,

and let my dearer country fill my breast,

To public good transfer each fond desire,

And clasp my country with a lover’s fire.

Well pleas’d her weighty burdens let me bear

Dispense all pleasure, and engross all care;

[ ] quick to [ ], to feel the public woes,

And wake, that millions may enjoy repose.

The strained verses were heartfelt even if not especially graceful or elegant. Perhaps a reader submitted the poem as their way of contributing to the struggle that colonizers endured throughout the imperial crisis and then intensified with the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington and Concord the previous spring. Sause aimed to make his own contribution by supplying “SMALL SWORDS and Cutteau de Chasse’s,” a type of sword, to the gentlemen of New York who prepared for the possibility that they would have to join the fight. Although Sause’s advertisement appeared below “The Patriot’s Wish” almost certainly by coincidence, the cutler may have been pleased with the happy accident. After all, the poem primed readers to think about their duty and to contemplate how to make their own contributions to the cause. For many, that could have included outfitting themselves with weapons and other military equipment.