What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“All sorts of Groceries as usual – except TEA.”

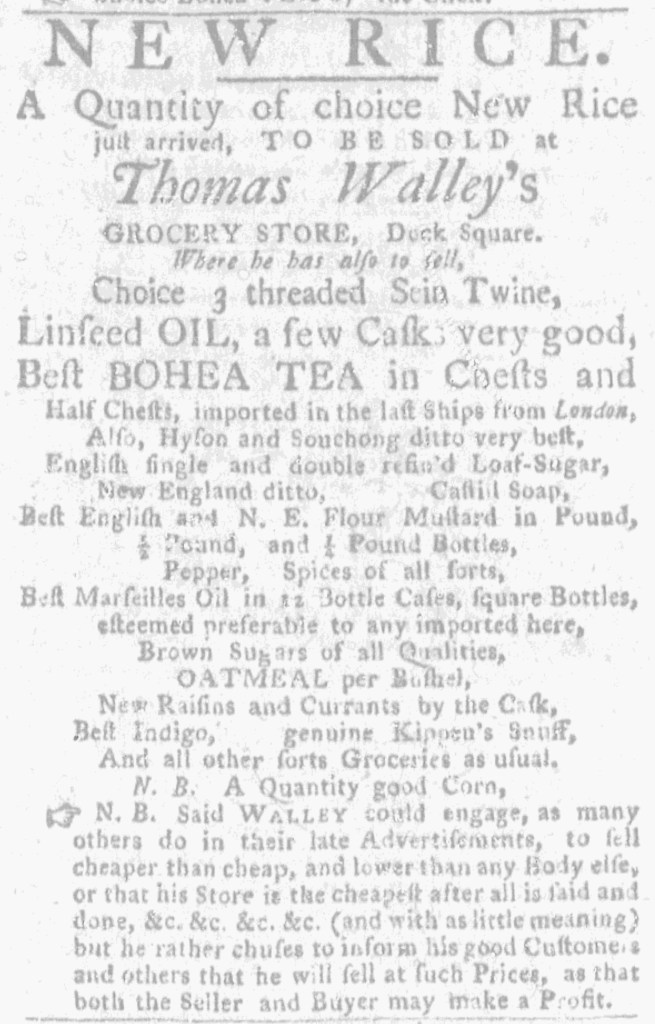

By the time that Thomas Walley’s advertisement ran in the May 12, 1774, edition of the Massachusetts Spy, it would have been a familiar sight to regular readers of that newspaper. It previously appeared on six occasions in March, April, and May, advising the public that Walley stocked a variety of items that he sold wholesale or retail at his “Store on Dock-Square” in Boston. He had “Dutch looking-glasses of various sizes,” “quart and pint Mugs and Chamber Pots,” and “choice junk” (or old rope) “to make into cordage of any size.”

Walley also sold “Oatmeal per bushel,” “all sorts of Spices,” “choice Rice,” “new Raisins,” and “all sorts of Groceries as usual – except TEA.” That last entry, listing what he did not sell rather than what he wanted to put into the hands of consumers, may have the primary reason that Walley inserted his advertisement in the Massachusetts Spy so many times. As one of the owners of the Fortune, the vessel that transported the tea involved in the second Boston Tea Party, Walley had been under suspicion, though he and his partners asserted that they did not have “any share, interest or property, directly or indirectly in any part of the Tea that came from London in said vessel.” They made that declaration, affirmed by a justice of the peace, in an advertisement that ran in the March 10 edition of the Massachusetts Spy, just days after colonizers disguised as Indians once again dumped tea into Boston Harbor.

A week later, Walley’s advertisement listing a variety of goods “except TEA” appeared in the Massachusetts Spy for the first time. Given the political orientation of that publication, printed by ardent patriot Isaiah Thomas, it made sense for Walley to take to the pages of that newspaper in his effort to convince the public that he was not trucking in tea. His advertisement ran again the following week and then on April 7, 15, and 22 and May 5 and 12, missing from only the March 31 and April 28 editions. Merchants and shopkeepers often ran notices for several months, but in this instance a desire to sell his inventory probably was not Walley’s sole consideration. He continuously reminded the public that he wanted nothing to do with peddling tea, probably even more so on May 12 when Thomas published a two-page Postscript to the Massachusetts Spy that featured the text of the Boston Port Act that closed the harbor until the colonizers made restitution of the tea they destroyed. As the crisis intensified, Walley sought to distance himself from tea.