What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

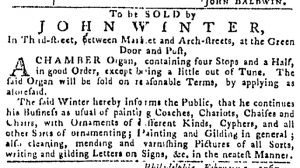

“To be SOLD by JOHN WINTER …”

Yesterday I questioned whether an advertisement for an escaped slave appeared regularly in the Georgia Gazette for six months because the aggrieved master wanted his human property returned so badly or because the printer needed content to fill the pages of the newspaper. Recently I have been contrasting the volume of advertising that appeared in newspapers published in major urban ports compared to those published in smaller cities and towns, usually noting how little advertising appeared in the latter.

Today I am featuring a newspaper at the other end of the spectrum. The Pennsylvania Gazette, founded in 1728 by Samuel Keimer but transformed into one of the most important and influential newspapers in the colonies after Benjamin Franklin in the decades after purchased it in 1729, often served as a vehicle for delivering advertising, sometimes at the expense of other content (including news items),

Consider the issue published 250 years ago today. David Hall and William Sellers, the printers of the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1767, placed at least some advertising on every page of the newspaper. Advertisements accounted for a quarter of a column on the second page and column and a half on the front page. Except for the colophon at the bottom of the last page, only advertisements appeared on the third and fourth pages. Nearly sixty advertisements of varying lengths filled just shy of eight columns, out of twelve total, in the February 12, 1767, issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette.

But wait: there’s more! A half sheet supplement accompanied the issue. Hall and Sellers granted a little space for the masthead. Otherwise, advertising filled all six columns of the two-page supplement. Many, but not all, were shorter than those in the regular issue, which allowed Hall and Sellers to squeeze in nearly sixty more paid notices. Unlike their counterparts in other cities, the printers of the Pennsylvania Gazette did not to insert advertisements about the goods and services they provided just to fill the page.

Historians of print culture in early America have long argued that any profits derived from printing a newspaper in the colonies derived from advertising revenue rather than subscriptions. By that measure, Hall and Sellers seemed to be doing very well for themselves as they published the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1767, presumably content to let advertisements sometimes crowd out other content. On the other hand, their decision to do so might also explain why William Goddard underscored that he intended “to give his readers a weekly relation of the most remarkable and important occurrences, foreign and domestic, collected from the best magazines and papers in Europe and America” when he issued his proposals for printing the Pennsylvania Chronicle, a competitor to the Pennsylvania Gazette. Perhaps Goddard suspected that some readers of the Gazette sometimes felt shortchanged when it came to reading actual news, rather than advertising, in their newspaper.