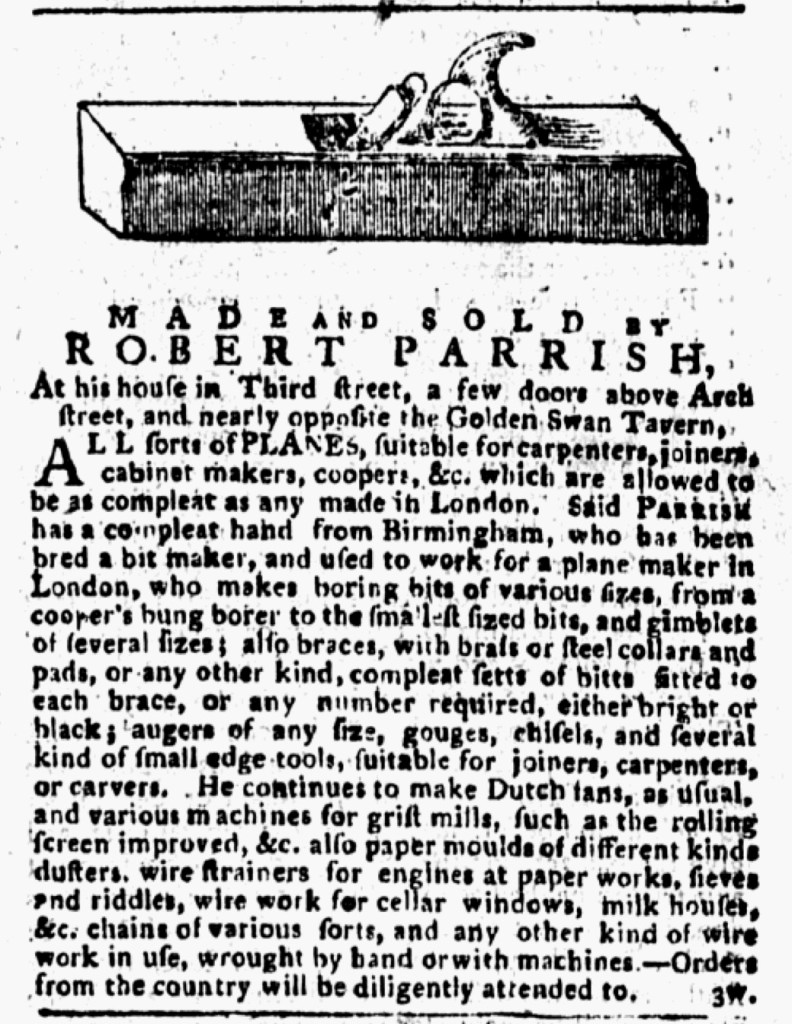

What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“ALL sorts of PLANES, suitable for carpenters.”

When Robert Parrish published an advertisement adorned with a woodcut depicting a carpenter’s plane in the August 26, 1775, edition of the Pennsylvania Ledger, it was the first of several appearances that image would make in newspapers printed in Philadelphia over the course of eight weeks. It next appeared in Story and Humphreys’s Pennsylvania Mercuryon September 1 as part of an advertisement with identical copy. Perhaps Parrish had clipped his advertisement from the Pennsylvania Ledger and delivered it to Story and Humphreys’s printing office along with the woodcut that he retrieved from the Pennsylvania Ledger.

Having commissioned only one woodcut constrained Parrish’s schedule for publishing his advertisements. Story and Humphreys’s Pennsylvania Mercury came out on Fridays and the Pennsylvania Mercury on Saturdays. That did not leave enough time to transfer the woodcut back and forth between the two printing offices and have the compositors in each include them in the new issues when they set the type and laid them out. Compositors, after all, sought to streamline that process as much as possible. To that end, the initial insertion of Parrish’s advertisement in the Pennsylvania Ledgerincluded a dateline, “Philadelphia, August 25, 1775,” above the woodcut, but the compositor did not include it with subsequent insertions (even though advertisements often ran with their original dates for weeks or months). It was much easier to retain the copy for the main body of the advertisement without worrying about a header that ran above the woodcut.

Parrish’s advertisement first ran in the Pennsylvania Ledger on a Saturday (in the first week of his advertising campaign) and then in Story and Humphreys’s Pennsylvania Mercury the following Friday (in the second week of his advertising campaign). It did not appear in the Pennsylvania Ledger the next day. Instead, it ran in that newspaper a week later (in the third week of his advertising campaign). In the fourth week, the woodcut returned to Story and Humphreys’s printing office and Parrish’s advertisement appeared in their newspaper once again on September 15. It did not run in either newspaper the following week but instead found its way to yet another newspaper, the Pennsylvania Journal published on Wednesday, September 27. That allowed enough time to get the woodcut back to the Pennsylvania Ledger for its September 30 edition (during the sixth week of Parrish’s advertising campaign). Parrish returned to alternating between the two original newspapers during the next two weeks. His advertisement with the woodcut went back to Story and Humphreys’s Pennsylvania Mercury for the October 6 issue and then ran in the Pennsylvania Ledger on October 14.

Investing in a woodcut increased the chances that prospective customers would take note of an advertisement, but Parrish and other advertisers had limits to how much they would spend. He apparently considered it worth it to commission a single woodcut but not more than one. Instead, he arranged to transfer that woodcut from printing office to printing office to printing office over the course of many weeks.