What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Mary Smith … will be obliged to the friends of her Husband for their Custom.”

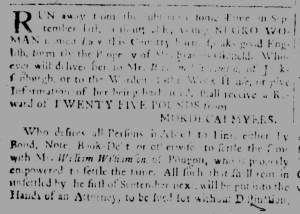

Following the death of her husband Thomas, a twine spinner, Mary Smith operated the family business on her own. In the summer of 1771, she placed an advertisement in the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy to inform “the Public, that the Business is continued at the usual Place.” She likely made a variety of contributions to the enterprise while her husband still lived, but became the proprietor and public face of the business upon becoming a widow.

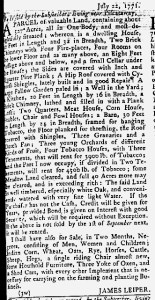

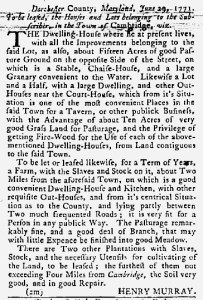

In that regard, she joined other colonial women who gained greater visibility as entrepreneurs when they ran newspaper advertisements after their husbands died. Mary Ogden, for instance, inserted an advertisement in the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury that “ACQUAINTS the Public, that the Business of Shoe-making is carried on as usual.” It appeared immediately below the estate notice she placed in collaboration with the other executors. Similarly, Mary Crathorne, administratix of her husband Nathan’s estate, advised readers of the Pennsylvania Gazette that the “mustard and chocolate business is carried on as usual.” Cave Williams adopted a similar strategy, following the estate notice concerning her husband Thomas in the Maryland Gazette immediately with an update that the “Smith’s Shop is carried on, by the Subscriber, with the same Care and Dispatch as was in her Husband’s Lifetime.”

Other widows who placed similar advertisements placed greater emphasis on some combination of sympathy and assistance from their communities. In the South-Carolina and American General Gazette, Elisabeth Russel stated that her deceased husband’s “SHIPWRIGHT BUSINESS is carried on as heretofore, under the Direction of a proper Person.” Even though she did not oversee the business directly, the advertisement noted that “Mrs. Russel will be much obliged to those that will employ her Hands.” Elizabeth Mumford was more overt in her effort to gain sympathy from prospective customers. She explained to readers of the Newport Mercury that “the Shoe-making Business is still carried on at her Shop in the New-Lane, for the Benefit of her and her Children, by JOHN REMINGTON, who has work’d with her late Husband several Years.” Mary Smith may have been making a similar bid for sympathy and assistance when she declared that she “will be obliged to the friends of her Husband for their Custom” and that “the smallest favours will be greatfully Acknowledged.”

In the advertisements they composed and inserted in the public prints, each of these widows made choices about how to present themselves and their businesses. Some more actively participated in the continued operations of those enterprises than others, but each probably had some previous experience from assisting their husbands in a variety of ways. They strove to convince prospective customers that they could depend on the same quality and skill without interruption.