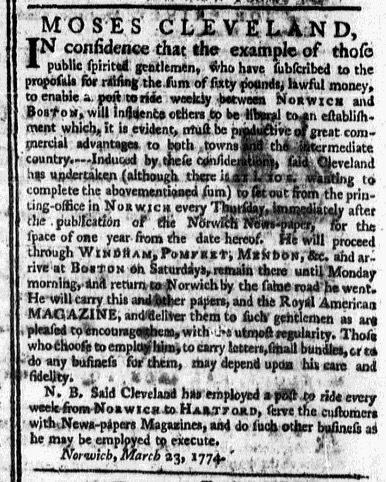

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Set off from the Printing-Office in Norwich every Thursday, immediately after the Publication of the NORWICH PACKET.”

When Moses Cleveland set about establishing a “Post to ride weekly between Norwich and Boston,” he simultaneously advertised in newspapers in both towns. His advertisements, dated March 23, 1774, first appeared in the March 24 edition of the Norwich Packet and ran a week later in the Massachusetts Spy. Cleveland covered a route that incorporated stops in both Connecticut and Massachusetts, including Windham, Pomfret, and Mendon. He advised prospective customers that he would “set out from the Printing-Office in Norwich every Thursday, immediately after the Publication of the NORWICH PACKET.” Customers in Connecticut received that newspaper hot off the presses, while those in Boston only waited a couple of days. He arrived there on Saturdays, delivering news from the west that the Boston Evening-Post, Boston-Gazette, and Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy might publish the following Monday. Cleveland remained there until Monday morning before returning to Norwich via the same route.

His advertisement in the Massachusetts Spy featured almost identical copy, though either the postrider or the printer, Isaiah Thomas, made some updates. In the Norwich Packet, Cleveland declared that he “will carry this Paper,” while in the Massachusetts Spy he stated that he “will carry this and other papers, and the Royal American MAGAZINE,” the publication that Thomas launched earlier in the year and had been promoting in the public prints from New Hampshire to Maryland for months. Perhaps Cleveland instructed Thomas to mention the magazine in his advertisement, but a revision to the nota bene that concluded the notice suggests that Thomas did so on his own. In the Norwich Packet, that postscript indicated that Cleveland “has employed a Post to ride every Week from Norwich to Hartford, [and] serve the Customers with this Paper.” In the Massachusetts Spy, on the other hand, the nota bene advised that Cleveland “has employed a post to ride every week from NORWICH to HARTFORD, [and] serve the customers with News-Papers [and] Magazines.” Had delivering the Royal American Magazine, the only magazine published in the colonies at the time, or any other magazines been among the services that Cleveland thought most likely to garner attention from prospective customers, he probably would have mentioned magazines in his advertisement that originated in the Norwich Packet. More likely, the savvy Thomas seized an opportunity to promote his magazine and assure subscribers beyond Boston that they would receive it in a timely manner.