What was marketed in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this month?

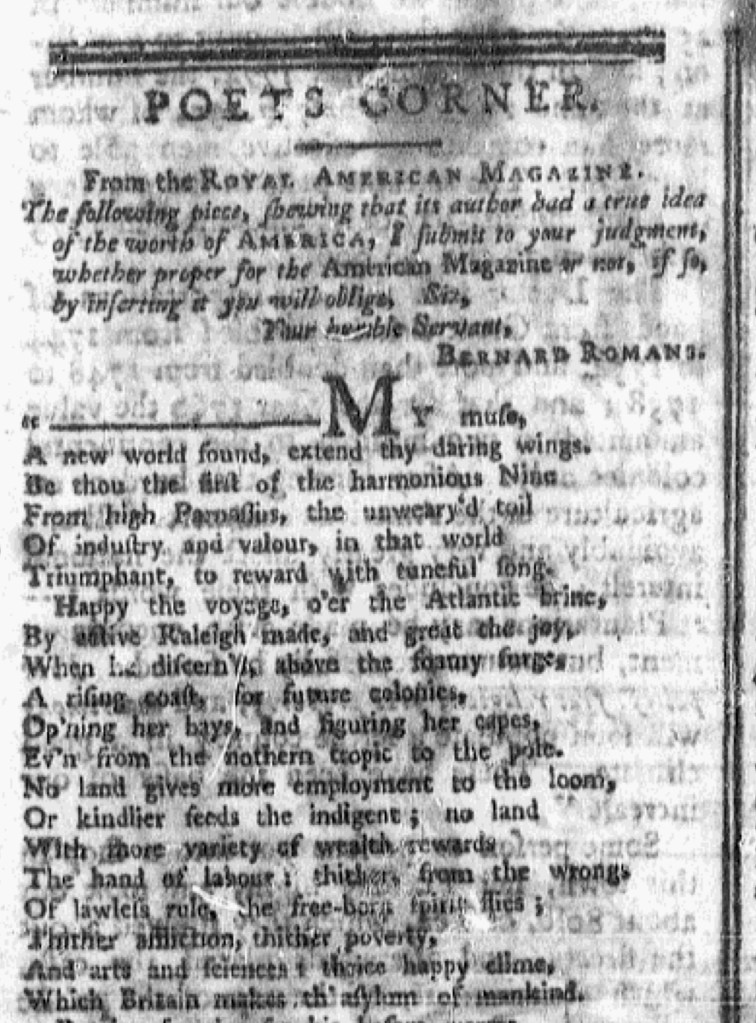

“From the ROYAL AMERICAN MAGAZINE.”

Isaiah Thomas did not publish any newspaper advertisements for the Royal American Magazine in July 1774. When he first proposed the magazine and sought subscribers, he ran advertisements in newspapers from New Hampshire to Maryland, sometimes dozens of them a month, yet once he published and distributed the first issue the extensive advertising campaign tapered off and, eventually, went on hiatus. The Adverts 250 Project has tracked Thomas’s efforts to promote the Royal American Magazine from the first time he announced his intention to circulate subscription proposals in May 1773 through the advertisements in newspapers in June, July, August, September, October, November, and December 1773 and January, February, March, April, May, and June 1774.

In the eighteenth century, publishers typically distributed new issues at the end of the month, unlike today’s practice of circulating magazines in advance of the publication date. Readers considered the January 1774 issue, for instance, an overview of that month, expecting to receive it just as February arrived. Even by those standards, Thomas was perpetually behind in delivering the Royal American Magazine to subscribers. He published the January issue on February 7 following a delay in receiving new types ordered for the magazine. The May 1774 issue did not appear until June 17.

Newspaper advertisements do not reveal when the June 1774 issue became available to readers. Thomas did not place any advertisements for the Royal American Magazine in July 1774, not even in his own newspaper, the Massachusetts Spy. As Frank Luther Mott documents, Thomas did announce in the June issue that “he was under the necessity of suspending the publication of his magazine ‘for a few Months, until the Affairs of this Country are a little better settled.’”[1] He lamented “the Distresses of the Town of Boston, by the shutting up of our Port, and throwing all Ranks of Men into confusion.”[2] The Boston Port Act, one of the repercussions Parliament instituted following the Boston Tea Party, took its toll on the Royal American Magazine. The magazine resumed publication in September, though by then Joseph Greenleaf was at the helm.

Although Thomas did not advertise the Royal American Magazine in July 1774, it did not go unreferenced in the public prints. The “POETS CORNER,” a regular feature on the final pages of many colonial newspapers, in the July 21 edition of the Massachusetts Spy featured a poem by Bernard Romans “From the ROYAL AMERICAN MAGAZINE.” It filled nearly an entire column. On occasion, Thomas inserted excerpts from the magazine in the Massachusetts Spy or the Essex Journal, the newspaper that his junior partner, Henry-Walter Tinges, published in Salem. That gave readers who had not yet subscribed a glimpse of the magazine’s content. For previous issues, Thomas had also attempted to incited interest by including an extensive table of contents in his advertisements along with descriptions of the engravings that accompanied each issue. Yet the lack of advertising for the June 1774 issue meant that he did not promote the frontispiece, “The Able Doctor, or America Swallowing the Bitter Draught.” That political cartoon condemning the Boston Port Act, engraved by Paul Revere, fit with the politics of the magazine. It remains one of the most significant images advocating the patriot cause produced in the colonies during the imperial crisis. As savvy as Thomas was about publishing propaganda, he missed an opportunity to call attention to such a powerful image.

**********

[1] Frank Luther Mott, A History of American Magazines, 1741-1850 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1939), 85.

[2] Quoted in Mott, History of American Magazines, 85.