What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“The vilest treatment perpetrated on any person … threatened my life and property with danger.”

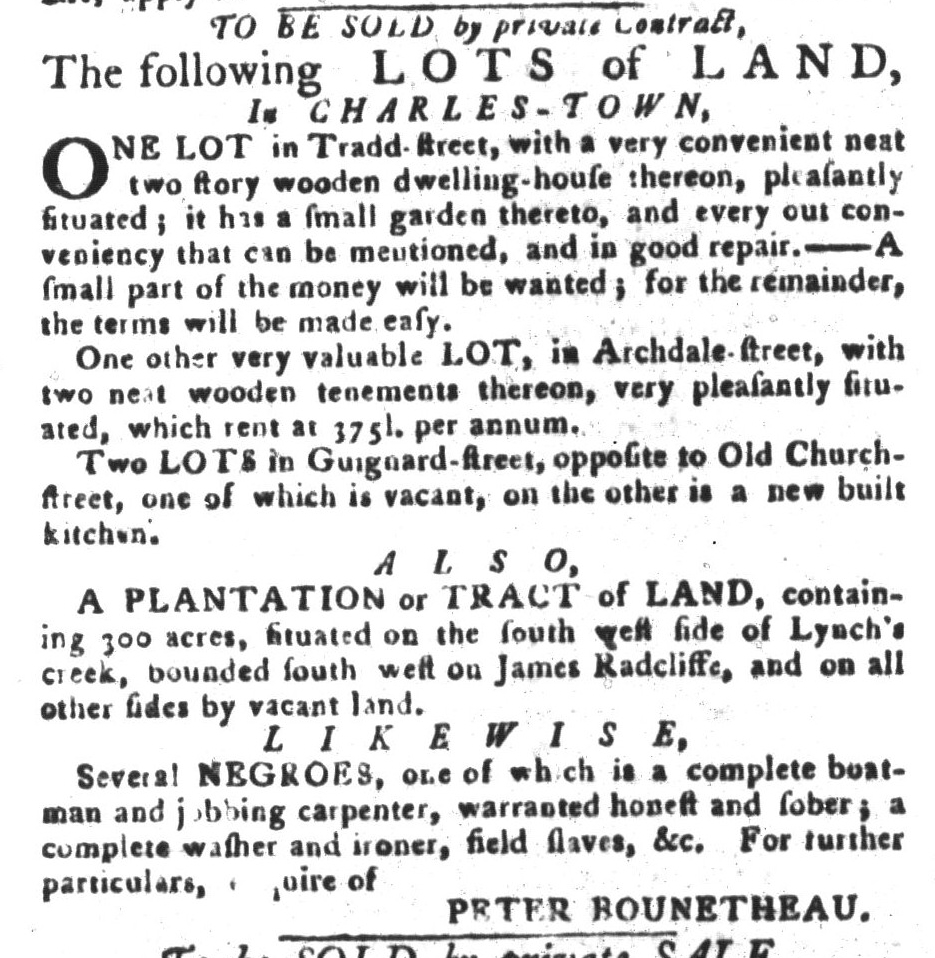

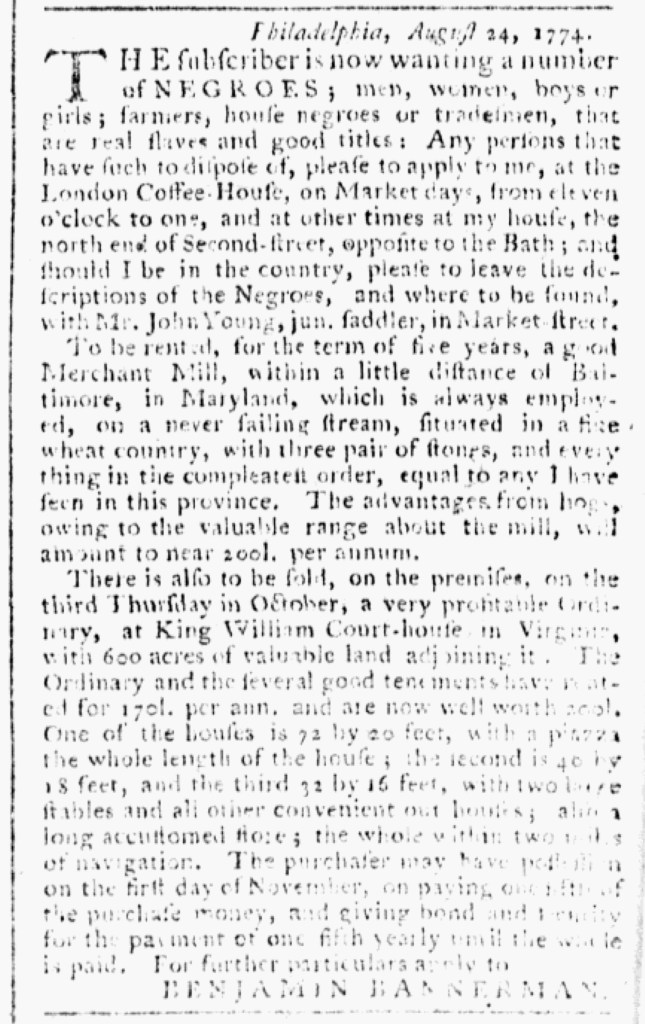

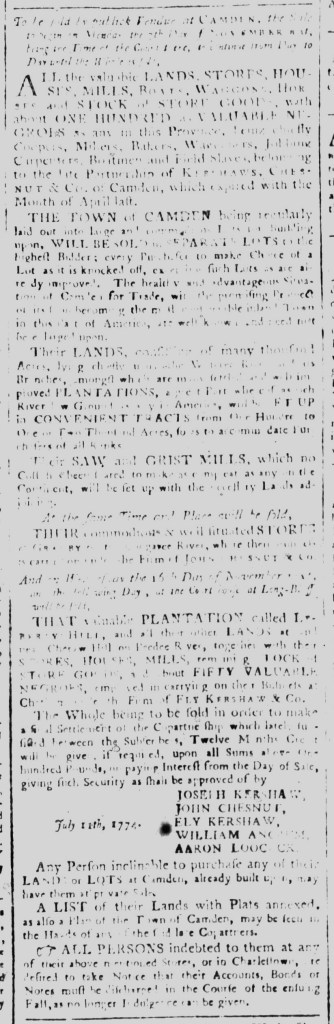

Eighteenth-century advertisers often used the space they purchased in newspapers to pursue multiple purchases. Merchants and shopkeepers, for instance, frequently devoted most of their advertisements to promoting goods for sale and then pivoted to calling on former customers to settle accounts. Sometimes the aims of the different portions of advertisements did not seem related at all. J. Musgrave devoted half of his advertisement in the August 31, 1774, edition of the Pennsylvania Gazette to leasing his “Wet and Dry Goods Houses and Stores” to merchants and the other half to buying and selling horses.

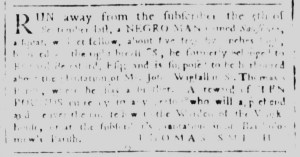

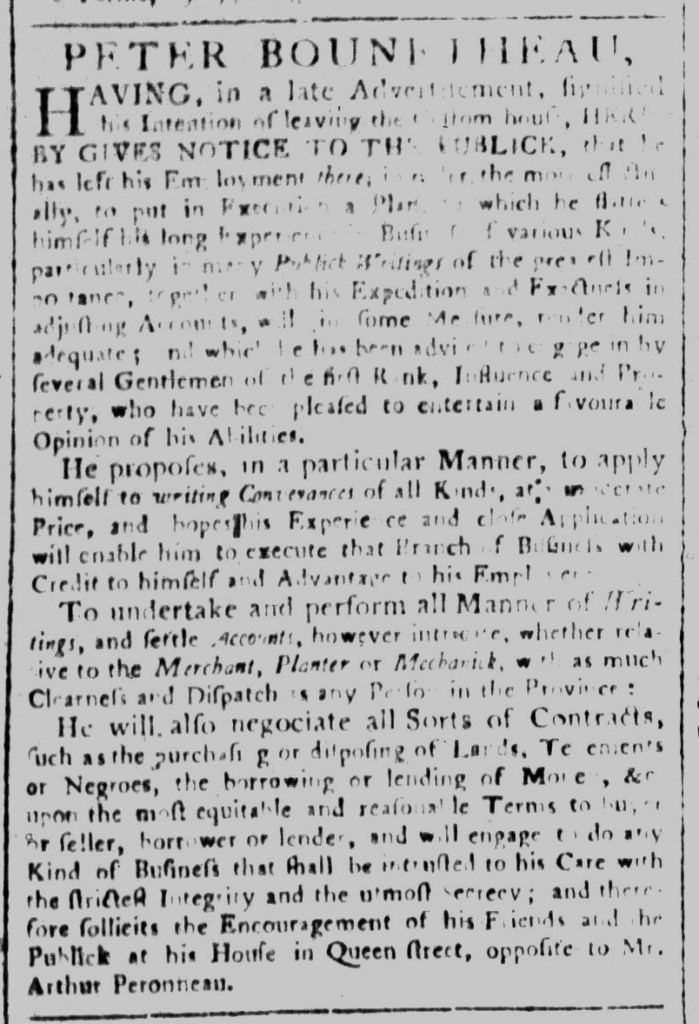

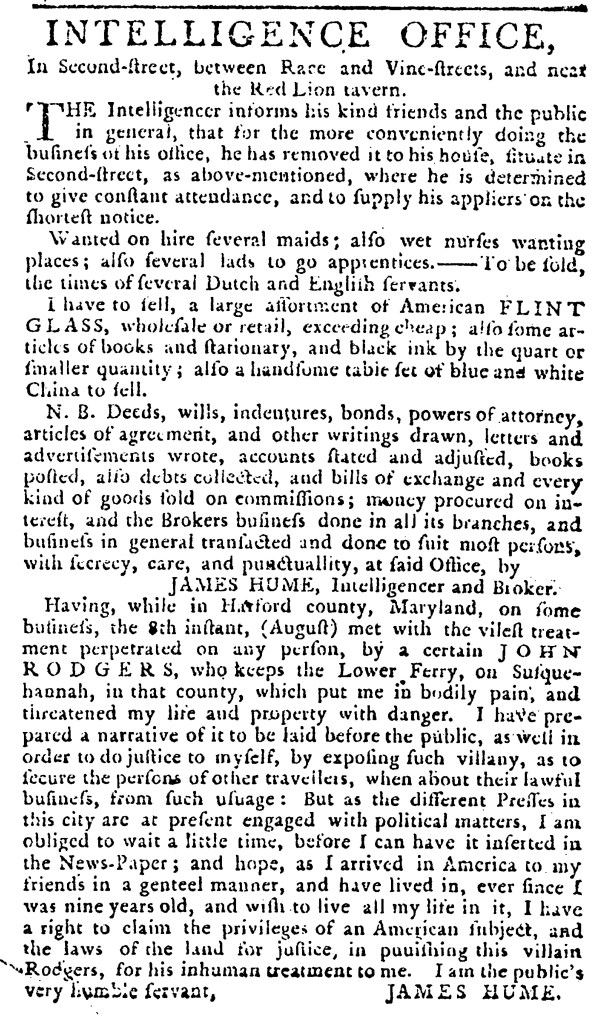

On the same day, James Hume published a lengthy advertisement with two very different purposes in the Pennsylvania Journal. The headline declared, “INTELLIGENCE OFFICE.” The broker described the various services he provided, including drawing up “Deeds, wills, indentures, bonds, powers of attorney, [and] articles of agreement.” He had “wet nurses wanting places” as well as “several lads to go apprentices.” He recorded and settled accounts, sold goods on commission, and even wrote advertisements on behalf of his clients. Rather than focus exclusively on his work as an “Intelligencer and Broker,” Hume used his access to the public prints to air a grievance against John Rodgers, “who keeps the Lower Ferry on Susquehannah” in Harford County, Maryland. According to the Hume, he was the victim of “the vilest treatment perpetrated on any person … which put me in bodily pain, and threatened my life and property with danger.” Following that ordeal, he “prepared a narrative of it to be laid before the public,” which he depicted as a service to the public. By “exposing such villainy” and warning others about Rodgers, he hoped to “secure the persons of other travellers, when about their lawful business, from such usage.”

Yet his intentions had been thwarted so far because “the different Presses in this city are at present engaged with political matters.” Hume had apparently shopped around to Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet, the Pennsylvania Gazette, and the Pennsylvania Journal, but none of the printers chose to accept his narrative for publication in their newspapers. Whatever their reasons for rejecting it, they invoked current events as justification. In recent months the imperial crisis intensified as the colonies received word of the Boston Port Act, the Massachusetts Government Act, and the other Coercive Acts passed as punishment for the Boston Tea Party. Parliament sought to restore order, but many colonizers believed their liberties as English subjects were under attack. For his part, Hume had his own concerns about his “right to claim the privileges of an American subject, and the laws of the land for justice, in punishing this villain Rodgers, for his inhuman treatment to me.” That incident, however, did not rise to the level that printers in Philadelphia gave priority to publishing it. Hume circumvented their editorial decisions, at least in part, by including his allegations against Rodgers in a paid notice, thus raising an alarm that others needed to be cautious when interacting with the ferry operator.