What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“THE BURLINGTON ALMANACK … IS JUST PUBLISHED.”

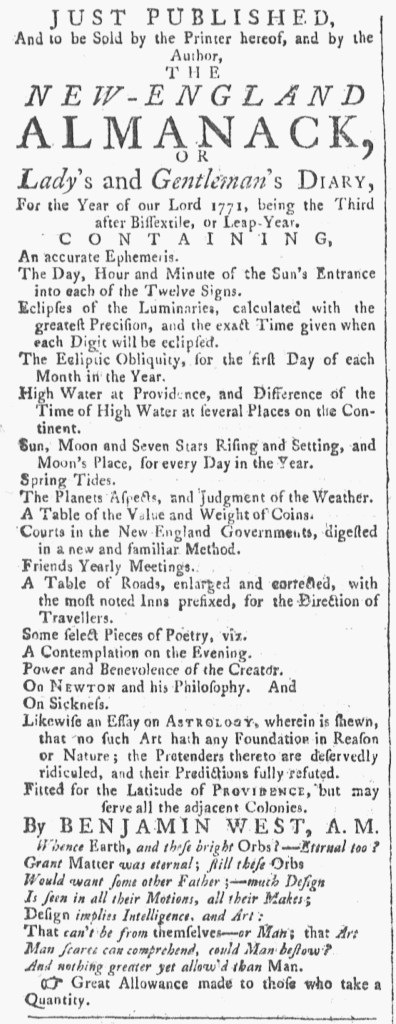

As they perused the September 7, 1772, edition of the Pennsylvania Packet, readers encountered a sign that fall would soon arrive. Isaac Collins announced that the Burlington Almanack, for the Year of Our Lord, 1773 “IS JUST PUBLISHED, and to be SOLD” at his printing office in Burlington, New Jersey. Hoping to entice customers, Collins provided a list of the “entertaining and useful” contents “Besides the usual Astronomical Calculation.” It was one of the first advertisements for almanacs for 1773 that appeared in colonial newspapers, an early entry in an annual ritual for printers throughout the colonies.

Publishing almanacs generated significant revenues for printers. Some produced several titles in their printing offices, catering to the preferences and brand loyalty of customers who purchased these handy reference manuals year after year. Marketing began late in the summer or early in the fall, often with printers declaring their intentions to print almanacs. In such instances, they encouraged readers to anticipate the publication of their favorite titles and look for additional advertisements alerting them when those almanacs were available to purchase. Collins dispensed with the waiting period. He made the Burlington Almanack available immediately, perhaps hoping to attract customers whom he suspected would choose more popular and familiar alternatives when other printers began marketing and printing them. After all, he first published the Burlington Almanack two years earlier, but others had annual editions dating back decades. Just five days before Collins’s advertisement ran in the Pennsylvania Packet, David Hall and William Sellers ran a brief advertisement about the popular “POOR RICHARD’S ALMANACK for 1773,” just three lines, in their own newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette. They announced that copies would go on sale the following day.

The number and frequency of advertisements for almanacs increased throughout the fall as printers shared their plans for publishing them and informed customers when they went to press. Some printers inserted brief notices about popular titles, as Hall and Sellers did. Other adopted the same strategy as Collins, disseminating lengthy descriptions of the “entertaining and useful matter” between the covers of their almanacs. Such material became even more important in marketing almanacs after the arrival of the new year. Printers often had surplus copies that they advertised in the winter and into the spring, the number and frequency tapering off. The “Astronomical Calculations” became obsolete with each passing week and month, but the essays, poetry, remedies, and other contents retained their value throughout the year.

Collins concluded his advertisement with a note that he “performs Printing in its various branches” and sold a “a variety of Books and Stationary, Drugs and Medicines.” Publishing almanacs accounted for only one of several revenue streams at his printing office, but an important one. Especially with effective marketing, printing almanacs could be quite lucrative for colonial printers.