I thought that the Adverts 250 Project was a challenging task to complete. However, when I officially completed the project, I felt accomplished and proud for all of the hard work that I had done. I am pleased to call myself a guest curator for the Adverts 250 Project. I was glad to have participated in the project and share my work with others.

Throughout my entire education, I have always expressed an interest in history. During middle school and high school, I was never given a project so extensive and detailed as the Adverts 250 Project. Usually my classmates and I were asked to analyze documents and then participate in a discussion. Following this, we would usually be asked to write an essay on the documents discussed or a reflection on what we thought of them. I did not always benefit from this repeated routine because we either needed to stay within a set of boundaries or we did not discuss the documents as explicitly as we should have.

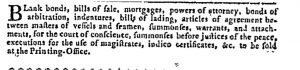

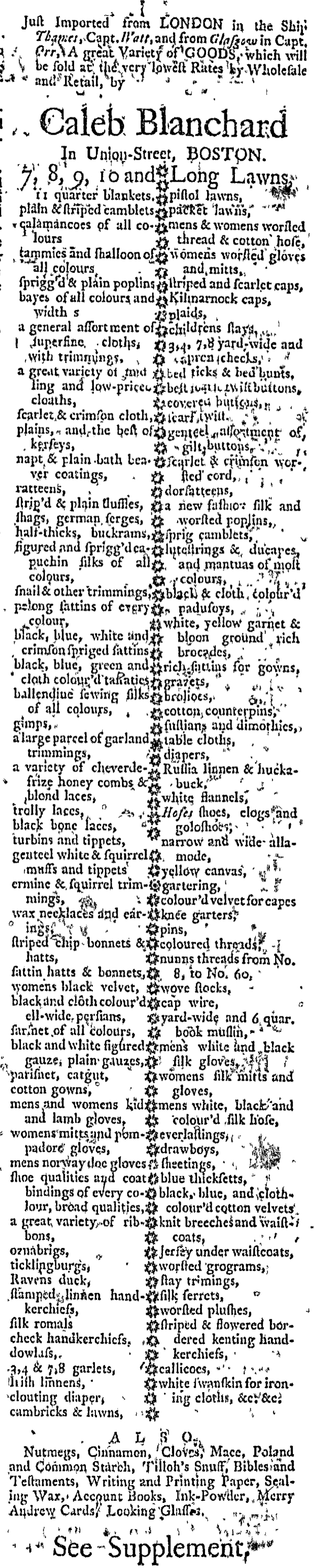

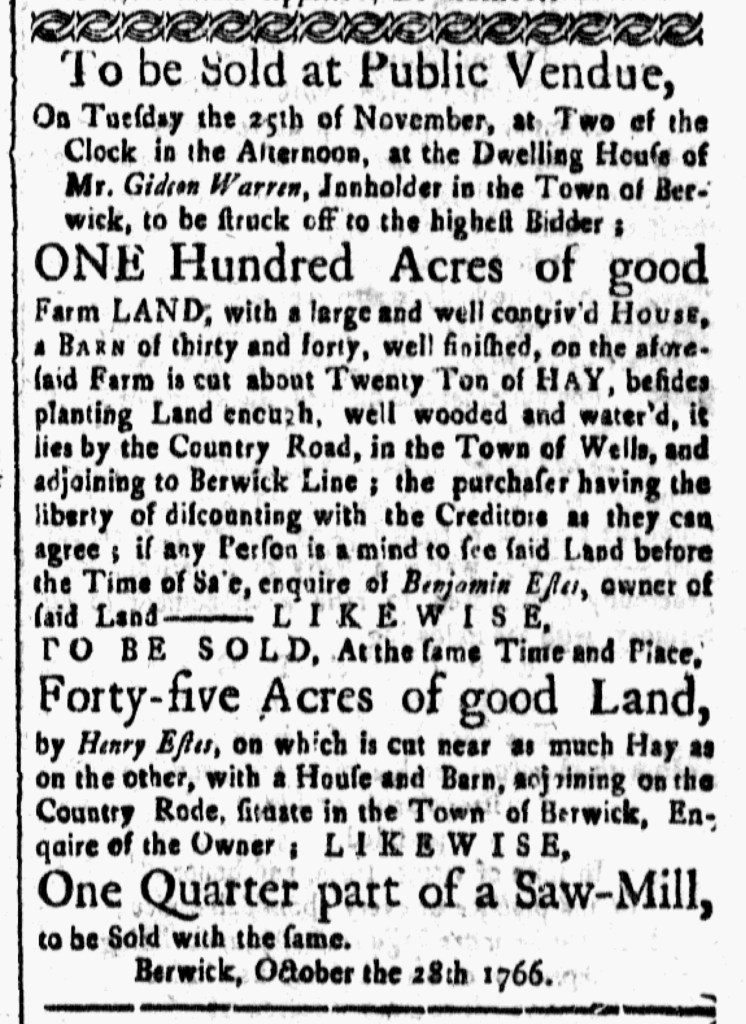

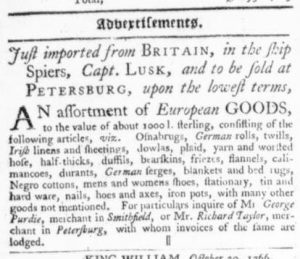

After choosing my own week for the Adverts 250 Project, I was asked to gather advertisements from 250 years ago that week. My goal was to find advertisements for colonial goods being produced, sold, or purchased. I was free to select any advertisements for goods of my choice from a vast number of newspapers.

I browsed through the newspapers for quite some time because I wanted to find advertisements that I knew either little or no information about. Some reflected upon something that I knew about, while others gave me a whole new learning experience. In regards to the newspapers, some were longer and more detailed than others. Thankfully, I managed to find an unfamiliar advertisement for each day as guest curator.

Once I chose my advertisements, I found it challenging to decode the text of each advertisement and choose a particular part or word to respond to. With that being said, it was difficult to visibly see and comprehend some of the terminology and phrases that were written. I wonder if it was because part of the text was naturally smudged when printed during the colonial era. In addition, I found it challenging to find online articles or databases that connected to either a word or phrase that I decided to focus on for my responses. I knew that I could not use one particular source multiple times for my responses. Despite these challenges, I knew that it was essential to continue searching for clues and connections that referred back to my advertisements. By doing so, I was able to expand my knowledge of colonial life and even imagine myself living during the era.

Prior to completing the Adverts 250 Project, I did not have a well developed understanding of the difference between various kinds of sources, such as primary and secondary sources. Additionally, I had a difficult time determining whether or not an article or website was accurate enough to use. Before I was a student at Assumption, I was briefly taught about source documents and the accuracy of websites and articles in high school. With that being said, I never fully developed a concrete understanding of either of these two concepts. Ultimately, it affected me and the way I analyze and write essays when I came to college. Thankfully, the Adverts 250 Project and my Colonial America class, in general, cleared up my past misconceptions and confusion of these two concepts. After completing this project, I feel like I’d be able to accomplish any other school project that involves primary and secondary sources or determining the accuracy of articles or websites.

I’ll admit that before I started this project, I never had my own Twitter account. At first, I was a bit apprehensive about completing this project because I did not understand how the social media site worked. Once a friend helped me create an account and taught me the basics of how the social media site worked, I felt more confident and prepared for what I was supposed to do. The Adverts 250 Project not only got me on Twitter but it allowed me to share my accomplishments and communicate with other history students and historians across the United States.

Upon my completion of the project, I learned how to accurately analyze a primary source and determine if an article or website is accurate or not. Additionally, I was able to expand my knowledge of colonial America by examining various goods that were bought and sold. Although this project had a lot of work and components involved, I encouraged others to experience it, whether that is by looking on the blog, the Twitter feed, or becoming an active guest curator.