What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

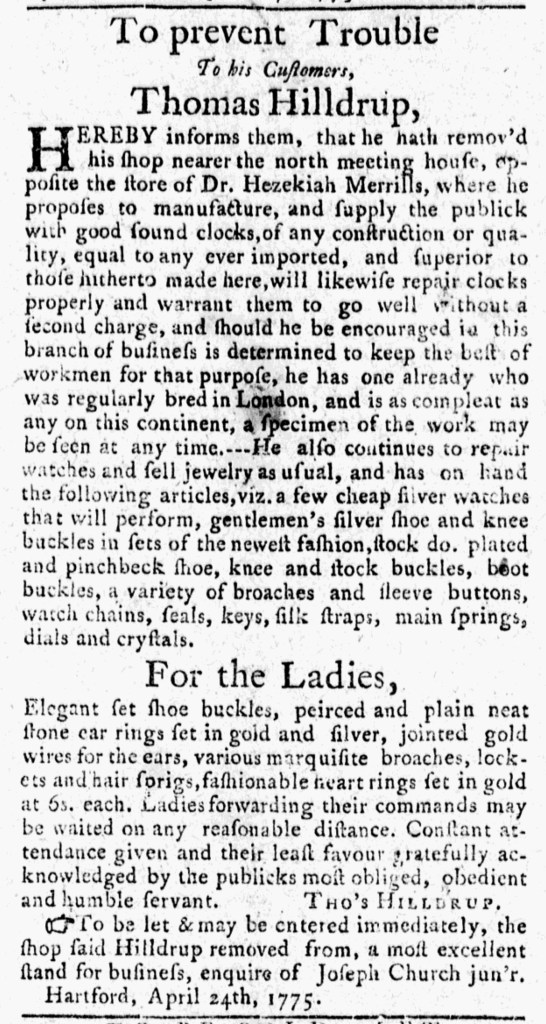

“To prevent Trouble …”

Thomas Hilldrup used a clever turn of phrase as a headline to draw attention to his advertisement in the May 8, 1775, edition of the Connecticut Courant and Hartford Weekly Intelligencer. “To prevent Trouble,” it proclaimed, inviting readers to look more closely to see what kind of trouble might be afoot. The headline stood out even more considering that most advertisements in that newspaper did not have headlines. Among those that did, some used the names of the advertisers as the headlines, such as “PETER VERSTILE” and “CALEB BULL, jun.” Hilldrup also used his name as a secondary headline on the third line of his advertisement. A few headlines indicated the goods or services offered in the notices, including “LEATHER BREECHES” and “WILL COVER” (the phrase commonly applied to stud horses).

When they looked more closely, readers saw a second line, “To his Customers,” in a smaller font than the primary and secondary headlines on the first and third lines. When they continued reading the body of Hilldrup’s advertisement they discovered his important message: “To prevent Trouble To his Customers, Thomas Hilldrup, HEREBY informs them, that he hath remov’d his shop nearer the north meeting house … where he proposes to manufacture, and supply the publick with good sound clocks.” Hilldrup devised a dramatic means of announcing that he moved to a new location! He ran the advertisement as a courtesy for those who might go looking for his former shop. It turned out that it was nothing as dire as threatening to sue customers and associates who did not settle accounts, nor did it have any connection to current events. Hilldrup first ran the advertisement on April 24, just days after the battles at Lexington and Concord. He may or may not have been aware of those skirmishes when he composed the advertisement, though he almost certainly realized that the imperial crisis could boil over at any moment. When his advertisement appeared in subsequent issues of the Connecticut Courant, readers no doubt searched the pages for new information about what was occurring in and near Boston and the responses in other places. That meant that a notice placed “To prevent Trouble” likely garnered more attention than other advertisements as readers perused the newspaper.