What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Large allowance to those who buy Quantities to Sell again.”

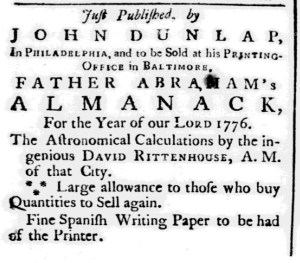

When John Dunlap published “FATHER ABRAHAM’S ALMANACK, For the Year of our LORD 1776,” in the fall of 1775, he set about advertising the handy reference manual. He gave the advertisement a privileged place in the September 11, 1775, edition of Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet, the newspaper he printed in Philadelphia. It ran immediately below the lists of ships arriving and departing from the customs house, increasing the chances that readers interested more in news than advertisements would see it. Unlike other printers who hawked almanacs, Dunlap did not provide an extensive description of the contents to entice prospective customers, though he did indicate that “the ingenious DAVID RITTENHOUSE … of this city” prepared the “Astronomical Calculations.” The printer believed that the astronomer’s reputation would help sell copies of the almanac.

He also ran advertisements in Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette, the newspaper he printed in Baltimore. One of those notices appeared in the October 31 edition, again highlighting Rittenhouse’s role in making the “Astronomical Calculations.” This advertisement did not include additional information about the contents, but it did include an appeal to retails that did not appear in the first iteration of the advertisement in Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet on September 11 nor in the most recent insertion on October 30. Dunlap promised a “Large allowance to those who buy Quantities to Sell again.” In other words, he offered discounts for purchasing in volume to make the almanac attractive to booksellers, shopkeepers, and peddlers. Did Dunlap offer the same deal at his printing office in Philadelphia yet not advertise it in the public prints? Other printers advertised discounts for buying almanacs by the dozen or by the hundred frequently enough to suggest that it was a common practice. Given that Philadelphia had far more printers than Baltimore, many of them publishing one or more almanacs of their own, Dunlap may have carefully managed the discounts, offering one rate in one city and another rate in the other. That did not necessarily matter to retailers who saw his advertisement in Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette. His printing office in Baltimore, opened less than a year earlier, gave them easier access to almanacs than in the past. The “Large allowance” was a bonus to convince them to take advantage of the convenience rather than order almanacs from other printers in Philadelphia or Annapolis.