What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

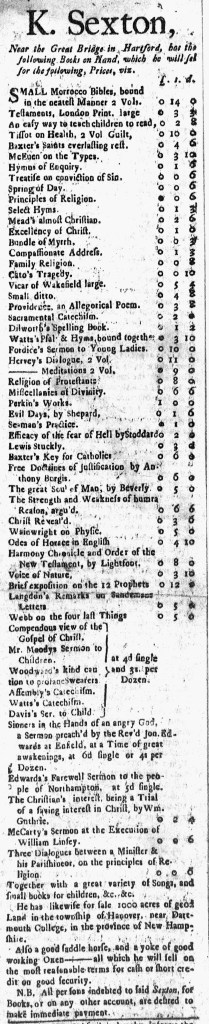

“He will sell for the following Prices.”

K. Sexton sold books at a shop “Near the Great Bridge in Hartford” in the early 1770s. Like many other early American booksellers, he placed newspaper advertisements that listed various titles available at his shop. In his advertisement in the January 8, 1771, edition of the Connecticut Courant, however, he included an enhancement not part of most newspaper advertisements or book catalogs published during the period. He gave the prices of his merchandise.

In orderly columns that ran down the right side of his notice, Sexton listed prices in pounds, shillings, and pence, allowing prospective customers to anticipate what they would spend on his books as well as identify bargains. He charged, for instance, fourteen shillings for a two-volume set of “SMALL Morrocco Bibles, bound in the neatest Manner,” five shillings and four pence for a “large” edition of a popular novel, The Vicar of Wakefield, and four shillings and eight pence for a “small” edition, and ten pence for “Cato’s Tragedy.”

For some items, Sexton sought buyers among both consumers and retailers. He sold “Sinners in the Hands of an angry God, a Sermon preach’d by the Rev’d Jon. Edwards at Enfield, at a Time of great awakenings” for six pence for a single copy or four shillings for a dozen. Retailers and others who bought in volume enjoyed a significant discount when they paid four shillings or forty-eight pence for twelve copies; Sexton reduced the retail price by one third. He offered similar savings for purchasing at least a dozen copies of six other titles, including “Mr. Moodys Sermon to Children” and “Watts’s Catechism.” For each of those, he charged either four pence each or three shillings (or thirty-six pence) for a dozen. Those who bought a dozen save one quarter of the retail price.

Most booksellers did not specify prices for their merchandise in newspapers advertisements that listed multiple titles, though they were more likely to mention prices in advertisements for single titles and almost always did so in subscription notices for proposed books, magazines, and pamphlets. In general, most purveyors of goods and services in eighteenth-century America did not indicate prices in their advertisements, except to offer assurances that they were low or reasonable. Setting prices and promoting them to prospective customers eventually became a standard marketing strategy, but it was not common in eighteenth-century advertisements. In the early 1770s, Sexton’s use of prices in his newspaper notices amounted to an experiment and innovation in marketing.