What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

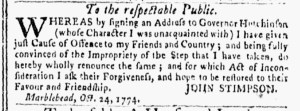

“By Signing an Address to Governor Hutchinson … I have given just Cause of Offence.”

It was another plea for forgiveness for exercising poor judgment, at best, or expressing unsavory political views by signing an address to Thomas Hutchinson that thanked him for his service as governor of Massachusetts. At the end of October 1774, John Stimpson of Marblehead took to the pages of the Essex Gazette to a acknowledge to “the respectable Public” that he had “given just Cause of Offence to my Friends and Country” when he had done so. He explained that he “was unacquainted” with Hutchinson’s character the previous spring, but in the time that elapsed since then he became “fully convinced of the Impropriety of the Step that I have taken.” That being the case, he placed an advertisement to “wholly renounce the same” as well as seek forgiveness for that “Act of Inconsideration.” Ultimately, Stimpson “hope[d] to be restored to their Favour and Friendship.”

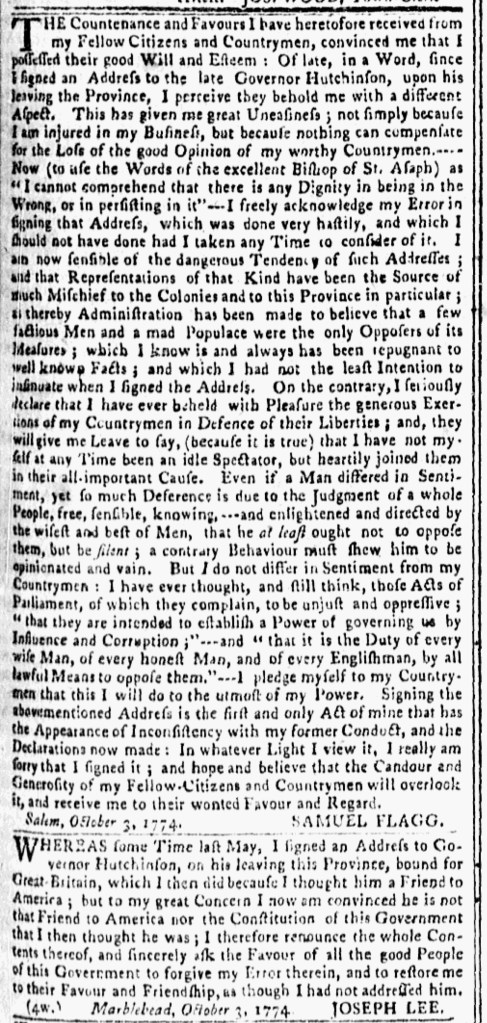

He was not the first to insert an open letter in the Essex Gazette or other newspapers for that purpose. Thomas Kidder published a similar apology in the Boston-Gazette in July 1774. Samuel Flagg and Joseph Lee each did so in the Essex Gazette three weeks before Stimpson did. Flagg’s extensive message to his “Fellow Citizens and Countrymen” incorporated an editorial on the “unjust and oppressive” legislation imposed by Parliament. Others published similar missives explaining their error, assuring the public that they were not admirers of Hutchinson (and, by extension, the Tory perspective on current events), and asking for forgiveness so they could restore their standing within their communities.

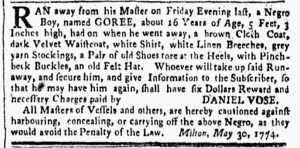

Stimpson’s version of what was becoming a familiar feature in the newspapers did not appear among the news and editorials. Samuel Hall and Ebenezer Hall, the patriot printers of the Essex Gazette, did not treat it as a letter to the editor to include alongside local news. Instead, it ran between an advertisement offering a reward for the capture and return of an enslaved man, Caesar, who liberated himself from his enslaver, and a real estate notice announcing the sale of a house and land in Long Wharf Lane in Salem. Stimpson’s message to “the respectable public” was an advertisement, a paid notice. The Halls did not extend the opportunity to seek absolution for free. They may have experienced a bit of satisfaction in generating revenue from someone who made such a poor decision in initially offering support to the royal governor so unpopular among Patriots.